As the Cuban missile crisis gripped the world’s attention 60 years ago, a less remembered conflict broke out high in the mountain passes of the Himalayas. Tensions had been mounting for months on the border between India and China and on October 20 the Chinese People’s Liberation Army attacked Indian forces on disputed territory and started the 1962 Sino-Indian war.

The origins of the conflict lay in two areas. First was the shifting, disputed frontier of colonial India, which ran across mountain peaks and glaciers. And second was the uncertain status of Tibet.

The Discoverer / WIkipedia, CC BY

Under Mao Zedong, China had “liberated” Tibet, and in 1951 Tibetan leaders were forced to sign a treaty allowing the establishment of Chinese rule. After a popular uprising in 1959, the Dalai Lama – the country’s spiritual leader – sought refuge in India, further straining Sino-Indian relations.

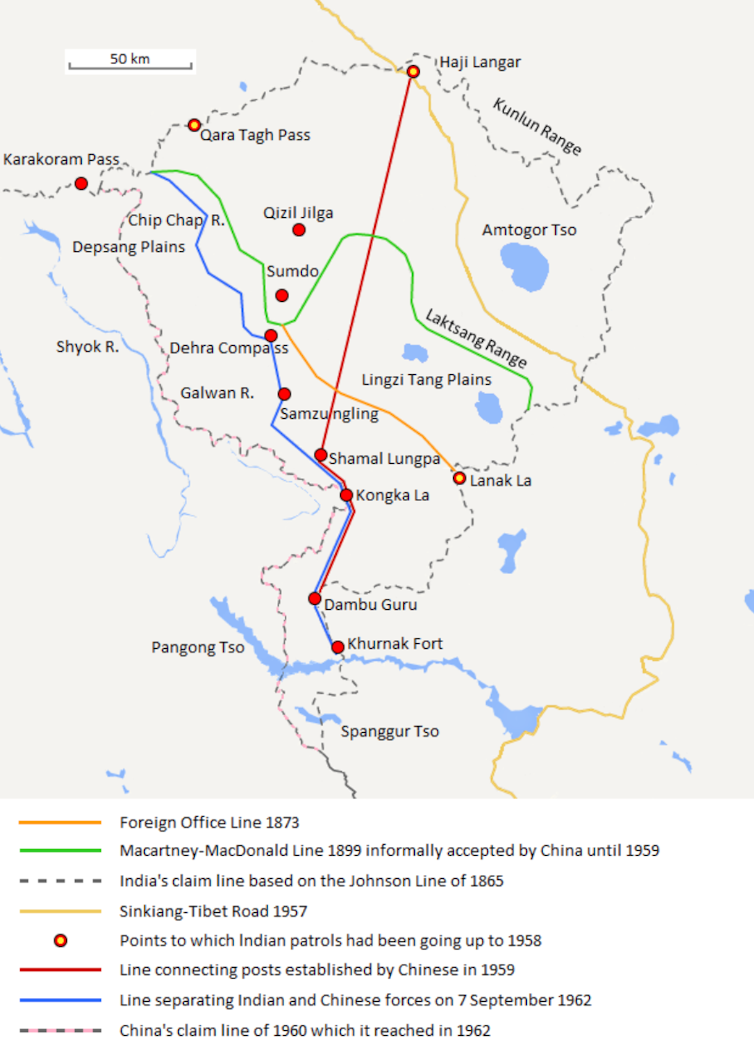

In four weeks of fighting across difficult high-altitude terrain, the better-resourced Chinese forces were eventually victorious, and China announced a ceasefire on November 21. Although Chinese forces withdrew from most of the captured territory, China retained control, contentiously, of 38,000km² of the Aksai Chin region in Kashmir which is an extension of the Tibetan plateau.

The geopolitical legacies of the 1962 war still trouble the two Asian superpowers. Further clashes occurred in 1967, and violence erupted again more recently in May and June 2020, when Indian and Chinese troops engaged in hand-to-hand fighting in Ladakh’s Galwan valley.

The Sino-Indian war is now remembered by political historians mainly for the reputational damage it caused India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. An admirer of China, Nehru dreamed of a great Indo-Chinese alliance.

He formulated Panchsheel (five principles of peaceful co-existence between the two countries) as a bilateral diplomatic code and endorsed popular slogans of Chinese and Indian brotherhood. India’s unexpected defeat in the 1962 war was a humiliation from which Nehru never quite recovered. His health declined, and he died just 18 months later.

While it soured Sino-Indian relations and overshadowed Nehru’s final years, the war had tragic longer-lasting consequences for members of the Chinese community in India, who suddenly found themselves transformed into enemy aliens in their adopted homeland.

A long-established Chinese community

Chinese travellers had visited India since antiquity. But it was not until British colonial rule and increasing trade across south-east Asia

in the late 1700s that Chinese people began to settle in the port areas of Calcutta and Madras (now Kolkata and Chennai). By the 1830s Chinese indentured labourers were also being recruited to work on tea plantations.

The Chinese community really became established in India in the early 1900s when a small number of Hakka Chinese immigrants arrived in Kolkata. In the segregated caste-specific occupations of the colonial city they found an economic niche in leather tanning and shoemaking, but ran shops and restaurants as well. Kolkata also became a home to Cantonese immigrants from Guangdong who operated joinery and furniture businesses, and incomers from Hubei who set up as dentists.

Historians estimate that at its height during the second world war, Kolkata’s Chinese community – which had its own schools, hostels, newspapers and temple “churches” in Bowbazar and then the eastern suburb of Tangra – numbered around 40,000. Today the community has barely 3,000 residents.

As tensions mounted prior to the 1962 war this long-established community was increasingly threatened. At the war’s outbreak the Indian government proclaimed the Defence of India Act which allowed the arrest and detention of anyone considered to be “of hostile origin” and targeted ethnic Chinese residents in India.

In the major cities, suspected Chinese Communist sympathisers were jailed. Peng Wenlan, who was born into the Chinese community in Kolkata, remembers her father, a respected school headmaster, describing how he was followed daily by the police. Worse was to come: in Kolkata and northeastern border towns in Darjeeling, Shillong and Assam, approximately 3,000 people were rounded up by the authorities and deported across the country in a special train to a former POW camp in the remote Rajasthan desert town of Deoli.

Oral history research by Kwai-Yun Li has recorded the experiences of the Chinese Indian civilians imprisoned at Deoli. The internees arrived after the November ceasefire and were confined in what Li describes as a concentration camp for years – the last internees were released in 1967.

They had been there so long that some children, including Joy Ma, co-author of the most recent history of the Deoli internment, The Deoliwallahs,

were born at the camp, while others tragically lost parents and family members there.

The experience of Deoli was profoundly destructive to the community because some were separated from close family at the start of their internment. For those who later tried to return to the north-east, a common experience was the complete dispossession of family businesses and property. In other instances, detainees were repatriated to China, even though they had lived in India for generations and sometimes did not speak a Chinese language.

There is now widespread recognition of communities made stateless by the shifting politics of decolonisation, such as Uganda’s Asian community which was expelled in 1972, but the history of the Chinese community in India and its diaspora is largely overlooked. Peng Wenlan’s family escaped before the deportations and arrived in Liverpool in the early 1960s, where her mother, a doctor, worked in the NHS.

Many more Chinese families emigrated to Canada. Former Deoli internees there have petitioned the Indian High Commission for some recognition of the historical wrong done to their community, but still await an official apology.

In Kolkata’s former Chinatown, remaining residents try to remain resilient, but continuing mistrust of China and the divisive experience of the COVID-19 pandemic threaten to dispossess this small community even further.

![]()

Alex Tickell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.