Forest. Full Moon. ink on hand made paper, 155x300cm, 2012

Turkish artist Selma Gürbüz is fascinated with shadows.

“Shadow is strength. Shadow is invincible. Nothing can overpower the shadow. Shadows follow you; they change,” said Gürbüz in an interview with Global Voices.

Gürbüz was born in 1960 in Istanbul, where she currently works. She graduated from Marmara University Faculty of Fine Arts in 1984 following two years at Exeter College of Art Design. Since her first exhibition in 1986, Gürbüz has been part of numerous solo and group exhibitions in both in Turkey and abroad.

Gürbüz’s works create worlds from imaginary creatures, ghosts, and threads drawn from The 1001 Nights, and draw inspiration from history. While her works might seem disconnected from the outside world or current events, they are fundamentally concerned with issues such as race, women, love, identity, and nature.

Excerpts from the interview follow.

Omid Memarian: How do you see the current position of Turkish contemporary art in the broader global scene? Have art events such as the Istanbul Biennale boosted the visibility of local artists?

Selma Gürbüz: Economic and political instability in Turkey have long affected the local art world. Collectors’ interest has slightly declined compared to previous years. However, I see this as temporary. A number of our important artists continue to produce works that make waves in the global art world. So, the interest that was shown in the works of Turkish artists both nationally and internationally remains. The Istanbul Biennale is one of the most important such events anywhere in the world.

Arter, a non-profit initiative that brings together artists and audiences in celebration of today’s art in all its forms and disciplines, relocated to a new venue last year. This new space boasts 18,000 square meters of indoor area and houses, exhibition galleries, terrace, performance halls, learning areas, library, conservation laboratory, arts bookstore, and a café.

The Odunpazarı Modern Museum opened in the city of Eskişehir. The Istanbul Modern Museum will soon move to a new, much larger building. There is no doubt that all these developments will greatly benefit the visibility and production of contemporary art within Turkey.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a considerable impact on the art world, internationally and within Turkey. International organizations will continue to be adversely affected, including through the impact on international travel, and therefore I think it is important that countries show more support and take an interest in their own artists, helping them to overcome these difficulties. The art markets will localize for a few years and this, in turn, will give a different kind of motivation to artists.

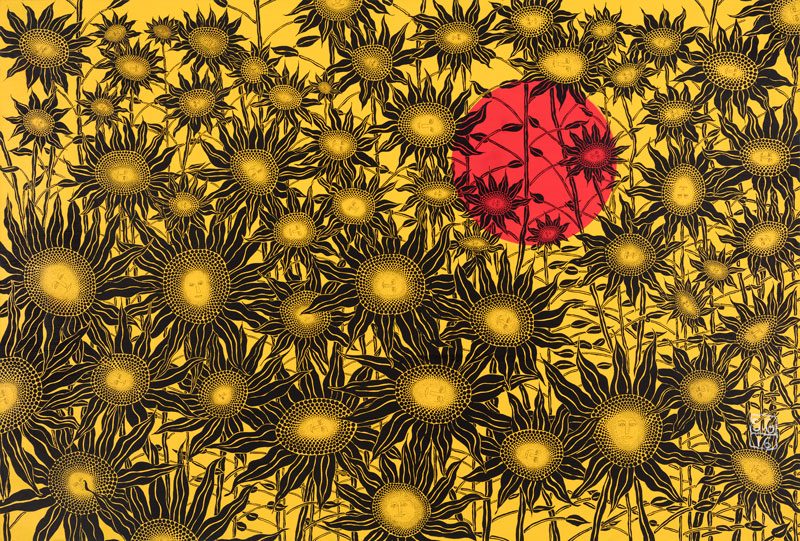

Maybe you feel like it, oil on canvas, 155x230cm. 2016

OM: The color black is dominant in many of your works. You have even been called “the painter of black magic, black crows, black people, fairies and eyes.” What’s your connection to this color?

SG: Black, for me, is fundamentally, shadow. In life, I’ve always enjoyed looking at shadows. My discovery of shadows is influenced not only by my interest in the shadow theater of my own country but also of the Far East, such as China, Japan, and Indonesia. Some of these shadow plays are quite vocal in their political discourse.

My first piece of shadow theater was an installation I prepared for the Kuandu Biennale in Taiwan. The papier mâché figures I created moved among themselves and I projected their reflection onto the wall. As well as their own movements, they threw black shadows onto the walls. Their movements transformed into an erotic theater piece.

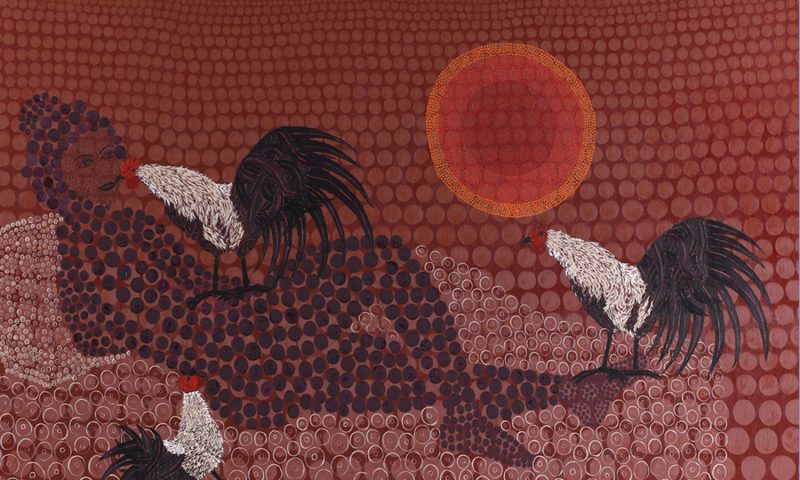

Later, I prepared other shadow plays for an exhibition of mine in Yokohama in Japan. In these plays I was also there within the shadows. It was a difficult piece. I was in front of the curtain this time, with the shadow puppets in my hands. They were animal puppets, roosters, ravens and suchlike. Along with my puppets, I entered into a performance that resembled a battle, an actual physical fight. It turned into a play in which the ostensible struggle was between such emotions as jealousy, passion, and vulnerability. In time, these black shadows made it into my paintings. Shadow means strength. Shadow is invincible. Nothing can overpower shadow. Shadows follow you; they change. Along with the movement of light itself, the position and form of shadow also changes. Shadow can change the shape of an object. Shadow lends length. That which is real does not change, but its shadow can change. Shadow is a two-dimensional representation. It shows us ourselves.

Woman with Roosters, oil on canvas, 155x230cm. 2011

OM: Women have a very strong presence in many of your works. What type of women do you speak about in your works, and what do they mean to you?

SG: I usually portray myself in my depictions of the figures of women in my paintings. The vulnerability, courage, caprices, and smiles of my female figures are reflections of my own feelings. They are the innocent figures of an undefined time. They are vulnerable. They are flirty. Instead of being in dialogue with the viewer, the viewer can instead form a strange closeness with them. They are mystical and naïve while also being courageous and intelligent. They have been trained in the ways of both the east and the west. Each one has a different story in my world. And I’m not talking here about a story as a product of fiction. These, instead, are stories that play out in an impromptu fashion; stories that have broken through into the free movement of the imagination. Every story gives birth to a new one and they all have this element of discipline and sustainability. For them, nature is extremely important, they feel the yearning for nature. They miss nature. These women see nature in its tiniest details, they study it, paint it, and wish to be consumed by it: to be lost in nature. It is this courage that gives them the power to be free.

Dance in the Forest, Ink on handmade paper, 61×118 1/10 in, 2013.

OM: Many of your paintings look like the work of a storyteller. How do you develop your stories and how do they end up as paintings?

SG: It starts with a mental picture. Then I ponder on which images I can use to compose that vision within a painting, and the kind of dramatic effect it will have. I have often felt that people who look at my paintings can read them like a story and that I have somehow enabled them to do so. But we have to distinguish here between this kind of storytelling and the compositional coherence of a literary author and the written tales that they build up through their layers, the gradation that takes place from start to finish as they compose drafts, erase, and rewrite.

In my creative process, the continuation of a spontaneous flow is clearly visible. I open up the doors to impromptu creation. There is nothing in my pictures that I cover up with something else. For example, I’d never say, “this part hasn’t turned out quite as I’d have liked, so I’ll change the paper.” Whatever I do is represented there. This is an idiosyncrasy that makes me, me. But at the same time, this can be a drag. The process requires the highest degree of concentration. What’s more, I have to know from the outset exactly what I want. Then again, that’s not to say that I will sit in front of a painting having toiled and performed every calculation. I like to leave myself to be free. My free form associations can cause the painting to flow in a new direction. And I feel it’s these surprises that make a painting a painting.

OM: Do current events impact your work and creativity?

SG: I don’t make political paintings. I don’t sit in front of a piece of work and feel the pressure of daily politics. The themes of the paintings, the subjects and contents are separate and are not influenced by everyday events in life or current developments. And therefore I can’t really say that I feel subject to a definite effect coming directly from that context. However, I am affected indirectly, there’s no doubt. And not only as an artist, I am affected first and foremost as a person. The disappointments I suffer in the outside world due to events that occur tend to turn me deeper into my own inner world. This is not a form of submission but can be better thought of as a stronger impulse to bring out the artistic powers. I say that I do not get directly affected, and then I suddenly remember a painting I made some three years ago. In the name of defending the rights and freedoms of those people who are oppressed in so many places in the world I painted a Statue of Freedom. The Statue of Freedom was only symbolic here of course. And to look at that painting again now in light of what is currently happening in the United States gives rise to new readings of it in totally new contexts and I personally find that very interesting.

Left: Ad Gloriam, ink on hand made paper, 220×120 cm. 2016. Middle: “Faced with Myself”, Archival Pigment Print 17/30 ed., 83x42cm,2012. Right: Serpentine. ink on hand made paper, 240x122cm, 2011.

OM: You were born, grew up, and live in Istanbul, Turkey, a country with a rich history and culture. How can one explore references to your roots and cultural identity in your works?

SG: Istanbul was the capital city of three huge empires: the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman Empires. It has a vast, rich, history and culture that very few other world cities can challenge. Istanbul’s rich identity results from a synthesis of “east” and “west”. When you take a walk on the historical peninsula of Istanbul you can see Ottoman miniatures, Byzantine mosaics, historical mosques and churches all of which are hundreds of years old, in just one day. Being born and brought up in a city such as this has had very direct effects on my art. For example, the Ottoman hunting miniatures or the paintings of Byzantine saints are only a few of the subjects I have portrayed. At the same time, the lands of Anatolia, which countless civilizations have made their home throughout history, are a place of incredibly rich mythology. Some of the references I go back to frequently for my paintings are those such as Kybele, the goddess figure whose roots we find in the Hittite and Phrygian civilizations. In addition to this, I love to return to universal myths, such as those of Adam and Eve or Medusa. I always find that I discover new points of view, new aspects, every time I go back to them.

Night. Sleeping Beauties. ink on hand made paper, 155x300cm, 2011

OM: What are you working on now and when we will see a new body of work? Will your new body of work be the continuation of your previous work?

SG: Two years ago I visited Tanzania with my friend Burak Acar. We went on safari in the Serengeti and took videos and photographs for a whole week. Africa opened new doors of inspiration to me. I’ve been working in Africa for a very long time. In November 2020 I will launch my new solo exhibition at the Istanbul Modern. In the exhibition my paintings and sculptures inspired by Africa will be exhibited. Alongside these we’ll be setting up various video installations showing the films that we took whilst in the Serengeti. At the moment I am directing a team and we’re working to get it all ready. I am really excited about this.