In a sermon in 1956, Martin Luther King distinguished negative peace (as the absence of tension) from positive peace (as the presence of justice). It is certainly plausible that a lasting peace would be of the positive kind. But when we reflect on what “justice” might mean, particularly economic justice (the justice of wealth and income), we notice an interesting dissonance between theory and practice.

In theory, the most influential concepts of justice are egalitarian, ones in which the concept of equality plays a central role. In practice, however, research shows that people are not so much concerned about equality, but about fairness. And while we often articulate fairness in terms of “just deserts”, the concept of this metaphorical desert has been consigned by most theorists to the philosophical scrap heap for being difficult to measure exactly.

Recent research gives us some hope: there is a way to understand fairness, which may put us on a safer path towards positive peace.

Inequality is fine for the lucky

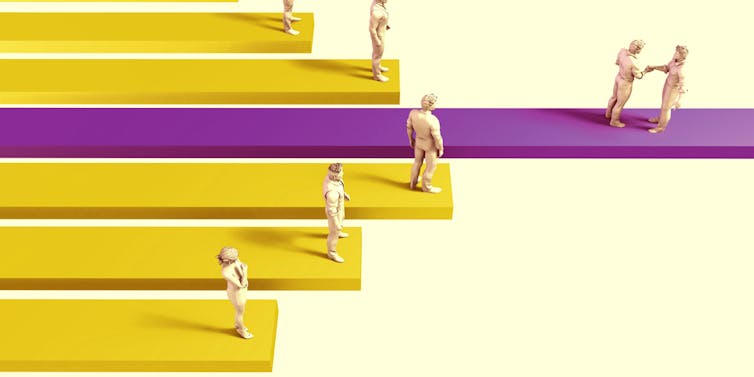

Let’s say you divide a cake for your birthday. Dividing it equally might be the fair distribution in this case, but often we end up with unequal, yet fair distributions (of cake or other goods).

Marcin Jucha/Shutterstock

Perhaps the most influential contemporary theory of justice was by John Rawls. His Egalitarian Principle on regulating the distribution of wealth and income requires that we divide all goods in society equally, unless unequal distributions are to the benefit of the worst off.

We may disagree with this principle because we usually profit from many contingent factors. For instance, we may have been born with rare talents, within an affluent family, group or country.

As members of the worst-off group, however, we would find Rawls’s principle justified, as we would if we did not know where, when, and how we would be born. This shows why, in theory, egalitarianism is so attractive and influential.

We do not value equality for its own sake

A standard approach to social, political and economic problems is to identify stark inequalities between individuals, groups and countries as the root cause. The solution is usually redistribution towards more egalitarian outcomes. Yet, recent research in philosophy, psychology and elsewhere questions the wisdom of such solutions.

First, is equality valued for its own sake? Consider a society in which everybody gets the same, but not enough. This will not be valued more than a society with huge disparities, where there is sufficient for all. Moreover, we usually react to being unfairly disadvantaged, rather than simply to not getting the same. Hence, restricting distribution to equal shares or conditioning unequal shares on being to the worst-off’s benefit, irrespective of how hard we each work, does not seem just.

Interestingly, more recent research draws a link between populist voting patterns in elections (in the US in 2016, and in France and the EU in 2019) and economic unfairness measured in terms of low social mobility. People are taking to the streets, as two economists wrote, not because they have less than others, but rather because they want fair opportunity. If distributive justice is a combination of equal opportunities and fair reward for talent and effort, then outcomes are likely to be unequal.

This isn’t a new conception of fair economic distribution, although it seems to have enjoyed more positive reconsideration recently. What this conception advocates instead is meritocracy.

Meritocracy was coined in 1958 by Michael Young, a member of the UK Labour Party and director of the party’s research office. In a meritocratic society social status is determined by “merit”, acquired through a combination of intelligence and effort leading to various significant social contributions.

Kentoh/Shutterstock

Yet, Young was critical of meritocracy, viewing it as a political system with low social mobility. What made it worse, he thought, was that it also gave the impression of fairness.

The fairness of distribution using just deserts

If what we want are fair opportunities without unfair disadvantage, then meritocracy cannot be the answer. Intelligence is at least to a significant extent hereditary. The ability to work hard is partly hereditary and the result of specific parental and social expectations.

Hence, the same groups of people will always end up at the top of the social ladder. This can hardly be just. Those at the bottom seem to be unfairly disadvantaged. It is interesting to see that the question often raised about the justice of various aspects of society is formulated in terms of what is “deserved”.

For example, we can criticise meritocracy and try to identify instead who really gets what they deserve. We could think a particular arrangement is fair (frontline NHS staff getting a bonus, for example), since it is deserved.

This need not refer only to fair distribution. An unfair decision in the courts is often challenged with the assertion that the victims have not had their just deserts.

We continue to use “desert” as a meaningful and powerful concept despite one of the most important British political scientists of the 20th century, Brian Barry, predicting in the 60s that the concept would disappear. When, in 1971, Rawls formulated his famous anti-desert egalitarian theory, it seemed to confirm Barry’s prediction.

The problem with a theory of distribution centred on the notion of desert is knowing exactly who deserves what – what is the result of responsible actions, attributable to us rather than to natural endowments and social circumstances. It may seem impossible to separate our just deserts from our unfair advantages or disadvantages.

But there is one way in which it might make more sense. This was suggested by John Roemer’s work on fair opportunities and applied to the question of how to ascertain desert.

Say, for one kind of achievement, the most relevant factors affecting performance are quality of education and IQ. We can then group together those who are affected by the same factors. For instance, one group will be of those with a better education, but lower IQ.

We can then determine relative desert by evaluating performance within each of the four groups. Comparisons across groups will tell us who are the most deserving. A person in the group of the better educated with high IQ may perform better than a person in some other group. But if the latter ranks in a higher percentile than the former’s, then we conclude she is more deserving.

Some goods should be distributed this way

To ascertain just deserts in this way, we need to rely on good empirical theories that identify the most relevant factors affecting performance. Depending on how advanced such theories are, we may end up with inaccurate conclusions.

There are goods which may fundamentally affect a person’s life (for instance, healthcare resources). We will want to avoid getting their distribution wrong. So we will allocate them on the basis of need.

Even if we could ascertain a person’s deserts accurately, there are still instances where this type of distribution seems undesirable. Consider hiring processes. We should aim to appoint the best neurosurgeon, even if they cannot take credit completely for their talent and effort.

Healthcare services and good education are essential for equal opportunity. They should be among the goods provided universally. Yet, ignoring desert for all goods disconnects completely distributive shares from what we do responsibly. We should then distribute at least some significant goods (say, bonuses) entirely on the basis of just deserts. This would be one good mechanism for increasing social mobility.

Fairness matters: systematic unfair discrimination increases conflict and tension in societies and international community. Fairness is importantly linked to responsibility and accountability. So a theory of distributive justice sensitive to desert is the way forward.

![]()

Sorin Baiasu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.