There’s something about mummies that always fascinates people. We see this from the attention given to mummies in museum exhibitions and in their frequent appearance in books, films and games. Perhaps it’s the fact that they are dead yet still very identifiable as people – in some way simultaneously dead and living. Whatever the reason, it’s always exciting when a study reveals new information about mummified remains.

Seqenenre Taa II was known as “The Brave” and ruled southern Egypt for a relatively short period around 1558 to 1553 BC. His rule came to an abrupt end when he met a very violent death. Now, researchers from Cairo University and Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities have used state of the art imaging techniques to reveal new details about this death.

A violent death

Seqenenre’s remains were first revealed in 1881, and examinations in 1886 and 1906 suggested he had been subjected to violent head injuries. In the 1960s, X-rays revealed five separate injuries on his head, but nowhere else.

On top of this, his embalming seemed to have been very hastily performed. Unusually, no salts were used to preserve the body, the brain was left in place and no linen was inserted into the cranium.

For Seqenenre Taa II, the violent injuries were possibly the result of dying in battle or execution by a king who had invaded the north of the country. One theory also suggested he was killed while sleeping.

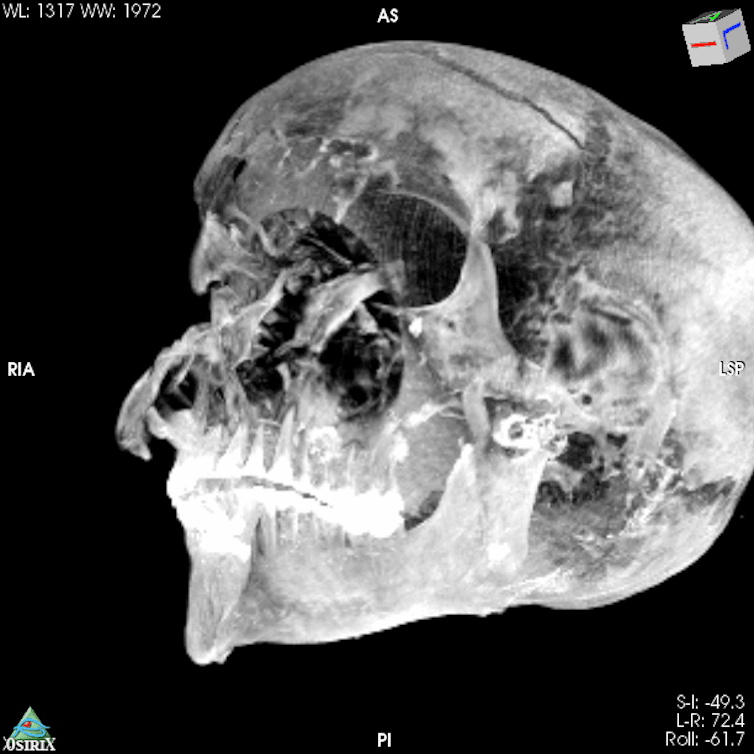

In the new study, the team applied computed tomography (CT) scanning to the remains to investigate further. CT is a non-invasive imaging method that basically layers multiple X-rays on top of each other in order to create three dimensional images of both the soft and hard tissues. We usually think of it in clinical settings, but it has a long history of use in forensic contexts to safely study remains contained inside wrappings or body bags.

Sahar Saleem, Author provided

The CT scans revealed the body was not arranged in its usual anatomical position. Even though it was in an unusual state, skeletal and dental indicators confirmed an age of around 40 years. Images of inside the skull confirmed that no attempt had been made to remove the brain. The CT examination revealed the extent of Seqenenre’s injuries, with a cut across the right side of his forehead, a puncture wound just above his right eye, a fractured nose and cheekbone, a cut on the left cheek area, fractures above his right ear, and a fracture of the bone inside his skull that runs behind the eyes.

Seqenenre suffered an incredibly violent death. The angle of the injuries suggested the attackers were positioned higher, so either on horseback or while he was kneeling, and facing him. The CT imaging allowed the shape of the wounds to be determined, showing that multiple weapons were used by multiple attackers. Yet such violent cranial injuries are usually accompanied by defence injuries on the arms as the victim attempts to defend himself. The CT scans confirmed that no such injuries were present here.

Sahar Saleem, Author provided

Most royal mummies from this period are laid with their arms crossed over their chest, but the position of Seqenenre’s hands suggests they were tied together and then fixed at the time of death, by a condition known as cadaveric spasm – where the body suddenly stiffens straight after death.

The researchers suggest the state of embalming was not a result of hastiness, but rather the condition of the body. There’s evidence the embalmers attempted to cover the facial injuries using a paste of embalming materials. While it’s unclear why the brain was not removed as was usual, I wonder whether the extent of the soft tissue trauma made this too daunting.

Mummification

Despite the excitement at finding mummified remains, preserved human remains aren’t uncommon in archaeological contexts. Mummies themselves have been found in a great many locations around the world, not just Egypt.

Mummification occurs when soft tissues are desiccated, or dried out, which can be due to heat but also air flow. Drying out stops decomposition and preserves the remains to the extent that identifiable features such as tattoos and fingerprints can still be recovered.

Last year, supposed preserved brain matter was found at Herculaneum, the site of an ancient town in modern-day Campania, Italy. Remains from the Bronze Age site of Cladh Hallan in the Outer Hebrides have also been mummified. I’ve even worked on a modern forensic case where the body had been mummified due to its position near a drafty window.

In all of these cases, and many more, techniques like the CT scanning used in this new research could potentially help reveal more information about the preserved people.

Read more:

Solved: the mystery of Britain’s Bronze Age mummies

The development of new imaging technologies is enhancing our interpretations of how ancient people died. Here, the application of CT scanning allowed for greater accuracy in age estimation and revealed new injuries that hadn’t been identified before.

Non-contact imaging techniques are being used in increasingly varied archaeological and forensic contexts as they become more accessible, more portable and record in greater resolution. Such advances will only help maintain our collective interest in our preserved ancestors.

![]()

Tim Thompson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.