Reparatory justice: ‘The greatest political movement of the 21st century’

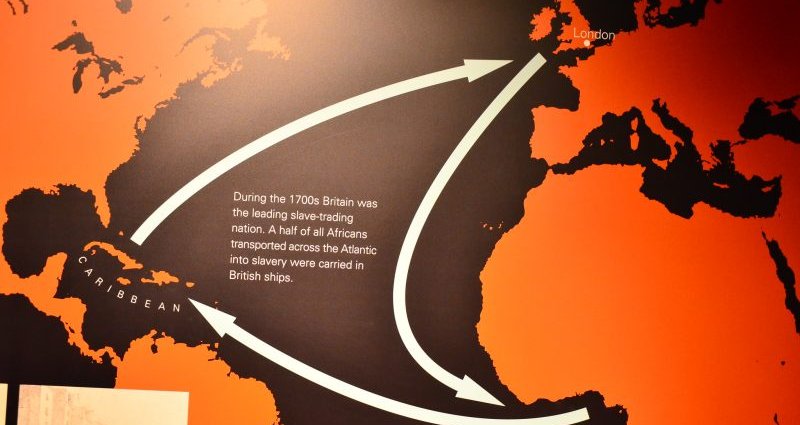

The slave trade triangle; photo by Ben Sutherland on Flickr, CC BY 2.0. The text reads: “During the 1700s Britain was the leading slave-trading nation. A half of all Africans transported across the Atlantic into slavery were carried in British ships.”

This is the second article in a series that highlights the question of slavery reparations in the Caribbean. (The first is here.) It is based around issues discussed in the NGC Bocas Lit Fest’s live stream event, “The Case for Reparations,” which featured an in-depth conversation with Sir Hilary Beckles, chair of the CARICOM Reparations Commission.

In commemoration of the International Day for Reparations, NGC Bocas Lit Fest, the Caribbean’s premier literary festival, hosted a session discussing issues around the need for slavery reparations in the region.

In this instalment of the series, Global Voices examines the many ways in which former colonial powers can make amends for their deliberate underdevelopment of the Caribbean.

The ‘slum’ of the British empire

As part of the terms of Caribbean independence, Britain’s former colonies asked for development funds to help put key infrastructure and public services in place, but were dismissed out of hand, prompting Eric Williams, Trinidad and Tobago’s first prime minister and one of the architects of the independence movement, to say:

The West Indies are in the position of an orange. The British have sucked it dry and their sole concern today is that they should not slip and get damaged on the peel […]

Interestingly, Britain’s colonies in the East Indies received 50 million British pounds [approximately 65,083,000 US dollars] under the Colombo Plan, which helped facilitate their transition to sovereignty. Sir Hilary Beckles, chair of the CARICOM Reparations Commission, attributes Britain’s rejection of the West Indies’ request for funding to the fact that the region was “the home of their white supremacy culture.” Black people, he said, were seen as not entitled to nor deserving of a development plan; in fact, former Prime Minister David Lloyd George once suggested that the West Indies were evidence of “a slummy empire” that would diminish Britain’s global prestige.

The ‘Arthur Lewis model’

The position of the CARICOM Reparations Commission is that Britain has a debt to the region based on the value of 200 years of free labour from 15 million enslaved people. That outstanding debt, Sir Hilary estimates, is worth about £7 trillion [just over US $9 trillion], which is more than the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). To settle it, there needs to be a major injection of capital into the Caribbean in order to lay the infrastructure for sustainable development — and building on what’s known as the “Arthur Lewis paradigm” is proposed as the way forward.

Sir Arthur Lewis was a St. Lucian economist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1979. Lewis had worked out a development model for the Caribbean based on drastic action to support economic reform and more equitable wealth distribution. Lewis proposed the Marshall Plan through which “wealthier nations should institute a system of grants-in-aid to enable poorer countries to improve their public service,” once writing:

The British […] are responsible for the presence in these islands of the majority of their inhabitants, whose ancestors have contributed millions to the wealth of Great Britain, a debt which has yet to be repaid.

Tangible measures that include debt cancellation, and investments in education, agriculture and public health would go a long way in helping the region find secure economic footing.

Apologies are not enough

In the wake of global protests around George Floyd’s murder and the revelations in the University College London database of the legacies of British slave ownership, the Bank of England and Lloyd’s of London were among various organisations that recently apologised for their “shameful” role in the transatlantic slave trade.

The CARICOM Reparations Commission, however, has made it clear that saying sorry is not enough. The way forward, Sir Hilary maintains, is an investment development fund to help at the site of the extraction, a model successfully used by the Colombo Plan as an investment for the public good. He views it as an integral part of the region taking responsibility for itself:

We transformed these broken colonies into functional democracies without any support. […] We have been borrowing money to support our development from Day One and now we have this debt crisis because we were abandoned by those who […] plundered our wealth. We had to go and borrow money from them to fund our own development. This is the cycle in which you are trapped into poverty. Reparations is one of those instruments that will help to break that cycle.

Calling the reparatory justice movement “the greatest political movement of the 21st century,” he added that it would unite people from all over the world who have been colonised, sending the message that they are no longer accepting this system of “civilisation” and that they want justice.

The importance of Africa

Caribbean Community (CARICOM) leaders, along with the CARICOM Reparations Committee, have been fastidious about taking the region’s demands to the United Nations, but they are still hoping for support from Africa, because of its tremendous global influence and advocacy weight within the African Union.

Some bilateral discussions have already taken place, but Sir Hilary believes that once African states “step up” into the conversation, it is going to be “the game-changer.” Far too many, he suspects, has “fallen victim to the notion that […] their antecedent governments were partners” in the atrocities of the slave trade — a narrative he calls “absolute mythology.”

You cannot have an international crime without a local partner […] but the presence of the local partner does not make the nation and the people of that society a partner.

Comparing the transatlantic slave trade with the illegal narcotics trade, he explained that European slave traders were so well equipped — both in numbers and in weaponry — that the lives of African leaders were often in jeopardy if they stood in the way. Nevertheless, there were many Africans who resisted and fought to end the trade.

The third and final instalment of this series will discuss the importance of universities in the movement toward reparatory justice — and the triple threat currently facing the Caribbean.