Should Azerbaijanis be wary of their close friend’s embrace?

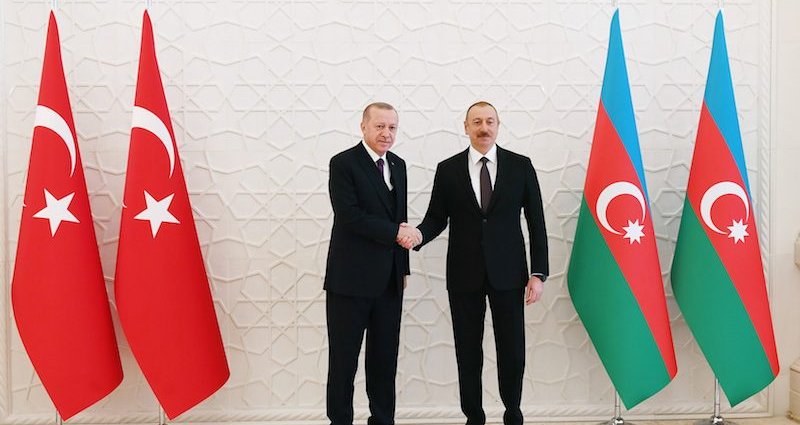

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan meets Azerbaijani President IIham Aliyev in Baku, February 2020. Photo CC-BY-4.0: President.Az / Wikimedia Commons. Some rights reserved.

This isn’t the first time in recent years when fighting has flared up in Nagorno-Karabakh.

But what is new, observers say, is the scale of the latest clashes — which can now be more accurately described as a full-blown war. Regional power brokers are also playing an increasingly important role in the conflict. If Armenia’s ally Russia has remained uncharacteristically remote, the same cannot be said for Azerbaijan’s close partners in Ankara. Turkey has offered extensive political and likely military support to Azerbaijan in recent weeks. International media have reported that mercenaries from Turkish controlled areas of northern Syria have been transferred to the South Caucasus to fight on Baku’s side — reports which the Azerbaijani authorities have roundly dismissed.

Turkey and Azerbaijan share the smallest of borders — Azerbaijan’s exclave of Nakhchivan borders eastern Turkey, though Nakhchivan is itself separated from Azerbaijan proper by Armenia and Iran. For decades, they were also divided by the Iron Curtain; Azerbaijan came under Soviet rule in 1920 and Turkey became a NATO member state in 1952.

However, Turkey and Azerbaijan also share Turkic roots, very similar languages, and a shared narrative about the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Turkey was the first to recognise Azerbaijan as independent after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, its relations with Armenia are officially non-existent; the long border between the two countries has been closed since the first Karabakh War in the early 1990s. Importantly, Turkey’s refusal to recognise the events of 1915 as an act of genocide continue to infuriate Armenian public opinion.

In this context, it is not surprising that Ankara remains a staunch supporter of Baku. But observers are increasingly wondering: why now? Why on this scale? And what role does domestic Turkish politics play?

To understand more, I spoke to Rovshan Aliyev, a former Radio Free Europe journalist from Azerbaijan who currently works as a media trainer in the Czech capital of Prague. This interview has been edited for brevity and style.

Rovshan Aliyev, photo used with permission.

Filip Noubel (FN): In what way is the escalation that started on September 27 different from previous bouts of fighting between Azerbaijan and Armenia?

Rovshan Aliyev (RA): Well, this is not a routine disruption of the [1994] ceasefire, something that has been happening occasionally on the frontline for years. This is almost a full-scale, continuous military operation. During previous standoffs, even in the most recent one in 2017, Armenia never openly threatened Azerbaijan with a military intervention to Azerbaijan, saying that the forces holding Azerbaijani territories are the self-defence army of Nagorno-Karabakh. But this time, we see a policy change, as Armenia is no longer hiding its direct involvement. On March 30, the Armenian Defence minister David Tonoyan declared that his country must prepare for “a new war for new territories” on the website Aravot.am. In May, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan participated in an inauguration event in Shusha, a city in Nagorno Karabakh that holds special significance for Azerbaijanis as a cultural centre and a place formerly inhabited almost exclusively by Azerbaijanis which has been since ethnically cleansed. More recently, Pashinyan’s wife, Anna Hakobyan also posed on social media holding a Kalashnikov rifle. Finally, in July, Armenian forces also shelled the region of Tovuz, which is situated inside Azerbaijan.

FN: Why is Turkey so prominently and openly supportive of Baku this time? What does it mean for Turkey’s ambitions and for Azerbaijan’s politics?

RA: Turkey was always supportive [of Azerbaijan] in terms of politics and diplomacy, but did not display direct military support. In 1991, Turkey recognised the independence of Armenia, but after Armenian forces occupied territories around Nagorno Karabakh, that is an additional seven districts of Azerbaijan, Turkey closed its border with Armenia. This was a form of economic sanction, but not a full-scale one, as to this day, the trade turnover between Turkey and Armenia amounts to several hundred millions of US dollars.

This time it seems that Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan wants to go beyond words and to support Azerbaijan with hardware. But I think such cooperation might harm more Azerbaijan than help it. Authoritarian leaders like Erdoğan try to take advantage of every situation, so Azerbaijan must be careful as Turkey’s direct involvement may complicate the conflict even more. So far, I don’t see any proof that the Turkish air force is directly involved. Concerning military equipment sales, it is not a secret that each side buys the weapon from several countries: Russia sells weapons to Azerbaijan, and sends more to Armenia for free, via Iranian territory. Azerbaijan has a US$1.6 billion contract with Israel, while Serbia has sold weapons to Armenia.

FN: Do you think Russia is unable or unwilling so far to impose a ceasefire, perhaps because of Pashinyan’s ambiguous position towards Armenia’s dependency on Russia?

RA: The previous political tandem in Armenia of President [Robert] Kocharyan and Prime Minister [Serzh] Sargsyan, the leaders of Russia and Armenia had a mutual understanding for many years, despite their interests being so different. In my opinion, the new Armenian leader Pashinyan [who came to power in 2018] felt himself alienated from this trio. As the revolutionary euphoria diminished in Armenia, the social, and then political crisis deepened, so Pashinyan desperately started to play the Karabakh card. I think he calculated that militarist behaviour might help him strengthen his position in Armenia. But Russia’s more neutral behaviour when compared to previous times shows that Pashinyan has miscalculated.

FN: In your view, what are the most optimistic and pessimistic scenarios for the coming days and weeks? Furthermore, Do you see space for dialogue in Azerbaijan and in Armenia? What voices are calling for it? If so, whose and where?

RA: I think [the conflict] will be shorter than Azerbaijan wants, but longer than Armenia and its international allies want. I always believed in people’s diplomacy, but the governments of all three countries have hindered such initiatives. On the Armenian side, most people are prisoners of the militarist ideology of the Dashnaktsutyun party, that has suppressed alternative voices. This group has fuelled the conflict from abroad, published many books, falsified many historical facts, and filled libraries with charged literature, particularly during the Cold War. Western powers were interested in the collapse of the USSR, thus the Dashnaktsutyun ideology was very suitable for this purpose. I’m against communism and the USSR, but I’m against using ethnic discrimination and ethnic conflicts to achieve their demise. The Azerbaijani rhetoric, including the militaristic and hateful speech which we see in the media, is a reaction to this Dashnaktsutyun propaganda. It is not a rational reaction.

Therefore, I personally know many Armenians, like Filip Ekozyants, a brave Armenian intellectual, who must be supported as alternative voices. Azerbaijani and Armenian people need a common project to find out ways to bring their positions closer. We must recognise that a century ago, Ottoman officials decided to deport Armenian people from their homes, and it resulted in a catastrophe, even some don’t want to use the word genocide. But we must also recognise that Azerbaijanis were not participants in this. A century ago two empires disintegrated: in the Ottoman Empire Armenians suffered, while in the Russian Tsarist Empire, Azerbaijanis suffered. Thus if some Armenians think that they must take revenge for Ottoman crimes in Nagorno Karabakh and other Azerbaijani territories, this notion is unrelated, unacceptable, and ridiculous. On the other hand, Azerbaijanis must be vigilant in order not to support neo-Ottoman rhetoric spread by Erdoğan supporters.

Read an interview with the Armenian politician and analyst Mikayel Zolyan here