The digital campaign features video messages from Holocaust survivors

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum is located on the site of the former Auschwitz concentration camp in Oświęcim, Poland. Photo by Meta.mk/Bojan Blazhevski, used with permission.

This story was originally published by Meta.mk. An edited version is republished here via a content-sharing agreement between Global Voices and Metamorphosis Foundation.

The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), an international organization that negotiates compensation and restitution for victims of Nazi persecution, continues to lobby Facebook to include Holocaust denial in its definition of hate speech. The digital campaign, which began in July and is targeted directly at Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, features video messages from Holocaust survivors.

“Holocaust denial posts on Facebook are hate speech and must be removed!” say the campaign’s creators and participants. Using the hashtag #NoDenyingIt, former inmates of Nazi concentration and extermination camps — as well as other survivors of the genocide during World War II — contributed powerful personal testimonies:

Beginning today the Claims Conference will be posting video messages across social media from #Holocaust #survivors imploring Mark Zuckerberg to remove Holocaust denial from #Facebook. Denying their suffering/loss is hate speech; there is #NoDenyingIt. Join them; share to remove! pic.twitter.com/kmpgq1KNuj

— Claims Conference (@ClaimsCon) July 29, 2020

Holocaust denial is the act of denying the Nazi genocide against Jews in World War II, and is considered a form of antisemitism.

One way to counter this form of disinformation is through education, which may include visits to memorial sites. For instance, the Auschwitz Memorial in Poland received 2,320,000 visitors in 2019. Entrance to the museum and bus transport between the remains of the concentration camp and the nearby city of Oświęcim are free of charge to visitors.

The museum, which has over 900,000 Twitter followers, over 300,000 fans on Facebook and 80,000 on Instagram, uses social media to teach history.

Meta.mk recently reported on a survey about Holocaust knowledge in the United States, conducted by the Claims Conference, which showed that young people lack basic awareness about the Holocaust. A significant percentage of respondents also hold many erroneous beliefs, including those coinciding with Neo-Nazi propaganda.

The study revealed ignorance of key historical facts among those between 18 and 39 years of age; 63 percent of respondents did not know that six million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, and 36 percent thought that “two million or fewer Jews” had been killed. Although there were more than 40,000 camps and ghettos in Europe during the Holocaust, 48 percent of US national survey respondents could not name a single one.

According to an Associated Press report, Facebook has said it already takes down “any post that celebrates, defends, or attempts to justify the Holocaust” or mocks its victims, because such posts usually violate many of the platform’s existing standards against hate speech and incitement of violence.

In compliance with local laws, Facebook has been removing all Holocaust denial posts “in countries such as Germany, France and Poland where Holocaust denial is illegal.” Thus far, however, the social networking giant has not specifically added Holocaust denial to its worldwide standard for hate speech.

The infamous cynical phrase “Arbeit macht frei” (“Work sets you free” in German) at the entrance of the Auschwitz concentration camp in Oświęcim, Poland, now part of The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Photo by Meta.mk/Bojan Blazhevski, used with permission.

In 2016, Facebook signed the European Union Code of Conduct on countering illegal hate speech online. After the code’s latest monitoring report on compliance, which was issued in June, showed that the company had highest rate of response in taking down notifications compared to other social media platforms, top Facebook officials expressed satisfaction with their progress in fighting hate speech.

Unlike Europe, where hate speech is a criminal offense in most of the countries that experienced the horrors of World War II, the US does not have such laws at the national level. However, social media platforms often adopt rules of conduct which ban hate speech, and many of them even go beyond the scope of law in their country of incorporation in order to ensure a safe environment.

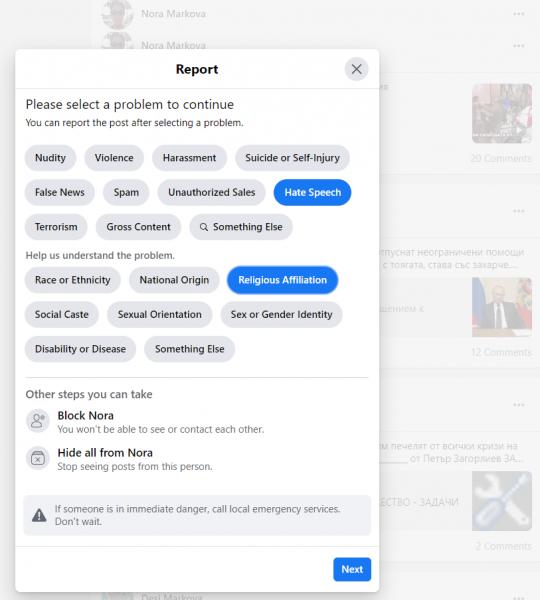

These internal governance rules set by the online platforms tend to function as self-regulatory mechanisms for users. Facebook, for instance, encourages its users to report instances of prohibited behaviors, and content that violates its community standards:

Example of the use of Facebook’s reporting system – in this case, of a post promoting Nazi propaganda. This option is available in the menu, under the link marked “…” at the top-right corner of each post.

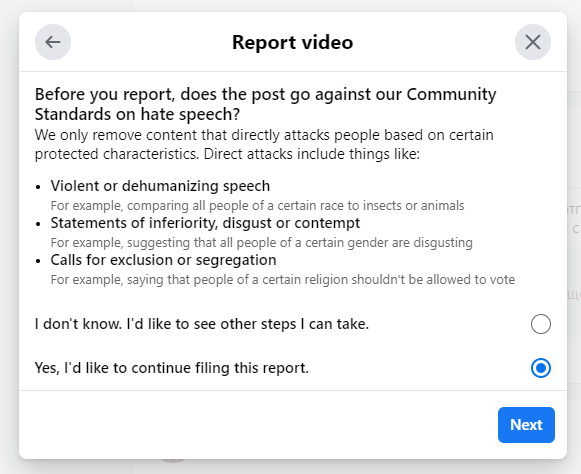

By clicking the “I agree” button on the terms of reference, social media users enter into a contractual obligation with the platform, whereby they promise to obey those rules. Users can also help enforce the rules by reporting breaches instances — including hate speech — as defined by the platform. Facebook currently classifies as hate speech as:

- “Violent or dehumanizing speech, for example, comparing all people of a certain race to insects or animals;

- “Statements of inferiority, disgust or contempt, for example, suggesting that all people of a certain gender are disgusting;

- “Calls for exclusion or segregation, for example, saying that people of a certain religion shouldn’t be allowed to vote.”

Part of Facebook’s reporting interface, which lays out the platform’s criteria for categorizing content as hate speech.

These categories cover only part of the range of legal definitions of hate speech as a felony used in the 47 member countries of the Council of Europe, an international body founded after World War II to uphold human rights and democracy in the region. Nearly all European states belong to the group, save for Belarus (due to human rights concerns) and the Vatican (because of its status as a theocracy).

According to the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers, “Hate speech covers all forms of expressions that spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance.” Sixteen European countries — as well as Israel — have specific laws against Holocaust denial. Many countries also have broader laws that criminalize genocide denial.

Article 407-A of the Criminal Code of Republic of North Macedonia, for example, states that those who “use information systems to publicly negate or severely minimize, approve or justify” acts of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, face prison sentences of one to five years. For those intending to incite hate, discrimination or violence against others based on national, ethnic or religious identity, the minimum prison sentence is four years. In the country’s recent history, there have been no recorded cases of such a felony.

“To the memory of the men, women, and children who fell victim to the Nazi genocide. Here lie their ashes. May their souls rest in peace.” The plaque is located at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Oświęcim, Poland. Photo by Meta.mk/Bojan Blazhevski, used with permission.

In addition to Holocaust denial, perpetrators of hate speech keep finding new ways to spread their messages, forcing human rights defenders and legislators to keep up.

In August, the Organization of the Jews in Bulgaria (Shalom) warned that far-right politicians were expanding their anti-Semitic language with new terms like “Sorosoids”, intended to label groups deemed “enemies of the state”. The term, based on misuse of the name of American philanthropist and Holocaust survivor George Soros, originated in neighboring North Macedonia as a populist propaganda tool for discrimination against civil society activists.

Editor’s note: Global Voices is a grantee of Open Society Foundations, an international grantmaking network founded by George Soros.