The internet perpetuates systems of oppression and inequality

A woman checks her mobile phone. Photo via Pikist, a royalty-free site for images.

Navigating the internet as a woman in Africa can be stressful if not straight-up dangerous. While digital spaces may appear free and equal, the reality is that the internet perpetuates systems of oppression and inequality.

In Africa, women and sexual minorities disproportionately experience harassment, doxing, non-consensual sharing and other forms of online gender-based violence (GBV). But a lack of robust, baseline data has made it difficult to determine the full extent to which women are threatened online.

Now, a large-scale research study — the first of its kind — reveals how African women living in five African countries experience the internet.

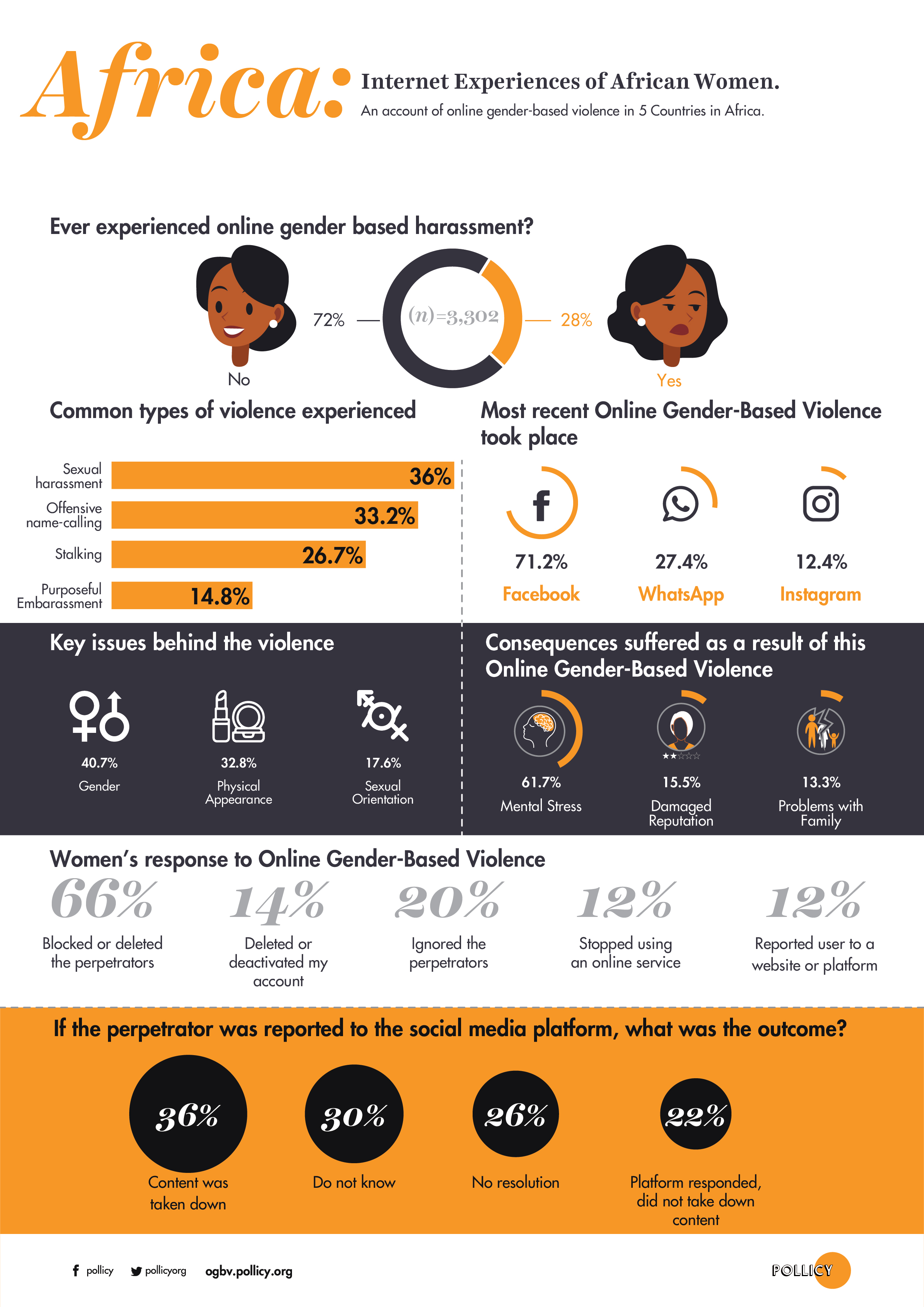

Over 3,000 women between the ages of 18-65, from Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Senegal, and South Africa, were interviewed about their “perceptions of digital safety, as well as responses to online GBV from a legal perspective, law enforcement authorities and technology platforms,” according to a press release.

A comprehensive report from the study entitled, “Alternate Realties, Alternate Internets,” aims to inform evidence-based policy to push for digital equality, explained Neema Iyer, the founder of Pollicy, the civic tech organization that led the research project.

“We want to understand how online gender-based violence manifests across Africa, and how technology companies, which are often based out of Africa, respond to this violence,” said Iyer.

Online GBV refers to targeting individuals based on their sexual or gender identity or by enforcing harmful gender norms, including behaviors such as stalking, surveillance, bullying, sexual harassment, trafficking, defamation, hacking, hate speech and exploitation and other controlling behaviors.

Pollicy, based in Kampala, Uganda, worked on this study in partnership with the Feminist Internet Research Network under the Association for Progressive Communication and with funding from the International Development Research Centre.

A website called “Survival Guide to Being a Woman on the Internet” encompasses a bot that walks viewers through interactive storytelling of the study findings.

The study found the 28 percent of women interviewed had experienced some form of online harassment. About 41 percent of these respondents believed that their gender was a primary reason for these attacks.

“Online threats are mainly organized trolling. I’ve received death threats,” said a woman from Kenya. “They come up with campaigns or a hashtag, so they rant at me all day. These insults are based on me as a woman, my anatomy, my family.”

In some countries like Ethiopia, 90 percent of respondents who experienced this online violence either did not know the identity of the perpetrator or found the perpetrator to be a stranger, and it was difficult to ascertain the primary perpetrator.

Online GBV takes a monumental toll on mental health, including depression, anxiety and fear that follows women offline at home, school, work and other social spaces.

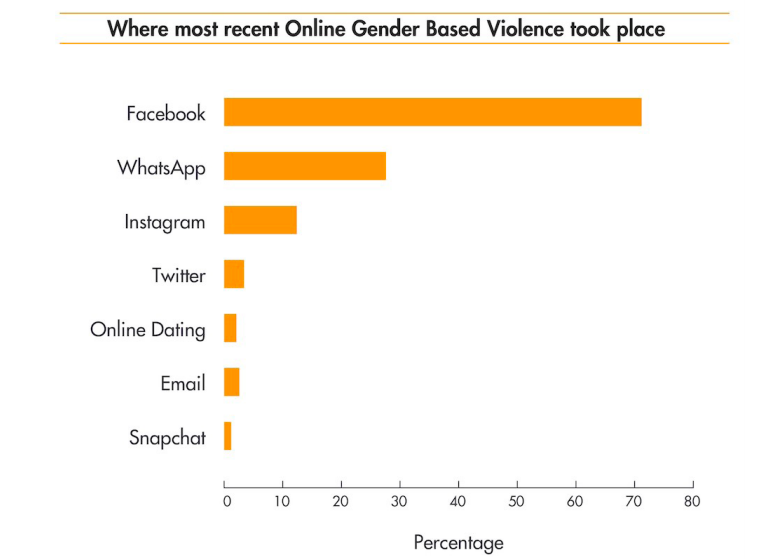

Screenshot from “Alternate Realties, Alternate Internets,” 2020.

‘Laws are not working to protect women’

While 71 percent of incidents of online harassment occurred on Facebook, results showed that up to 95 percent of the women were not aware of any policies and laws in place to protect women against online GBV.

About 15 percent of women interviewed said they deleted or deactivated their accounts whereas 12 percent stopped using a digital service after experiencing online violence.

“Women are not reporting even domestic violence because of the culture and the norm,” said a woman from Ethiopia. “Imagine going to report online gender-based violence. They are going to make fun of you and tell you to come back when the real violence happens,” she continued.

The report asserts that “violence against women online is often trivialized with poor punitive action taken by authorities, further exacerbated by victim-blaming.”

The report also confirms that most African countries “do not have specific legislation or strategies against online gender-based violence. Existing preventive measures to specifically target online gender-based violence are lacking.”

Read more: The identity matrix: Platform regulation of online threats to expression in Africa

Courtesy of Pollicy.

In partnership with Internews, Pollicy analyzed the laws on online GBV in each of the five countries and found that “online GBV cases rarely make it to the courtroom at all,” seriously limiting any analysis of current legal frameworks in place.

However, all five countries have ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), “which explicitly requires states to ensure that both men and women have equal enjoyment of the rights set out therein,” according to the legal analysis.

The African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, to which all five countries are also signatories, also affirms equal rights regardless of sex.

All five countries have also ratified the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). But Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda have not ratified the CEDAW optional protocol that allows for CEDAW committees to process and listen to complaints.

Toward a cyberfeminist future

The inherent whiteness and maleness of the internet today perpetuates inequality and props up patriarchal structures that oppress women and sexual minorities.

By contrast, cyberfeminism “offers a space for feminist thinking to critique, imagine and recreate a radically open internet,” according to the report.

Drawing from black feminist thought and feminist-informed tech theory, the report encourages the centering of women as “protagonists in technology-dominated Afrofutures.”

“How can we create a feminist internet?” Courtesy of Pollicy.

Iyer says there is an urgent need for digital security resources to be adapted to local contexts and languages, as well as mainstreaming these concepts in educational curricula.

Other recommendations include training law enforcement on how to address GBV violations and to provide assistance and counseling to women who choose to report.

African countries must also adopt and adequately implement data protection and privacy laws.

“When thinking of our Afro feminist future, we need to think of an internet where both the developers and users understand the intersectionality of the lived experience of an African woman,” said Iyer.