Contrary to the expectations of many observers, the “red wave” stopped at the House of Representatives and only delivered the Republican Party a small majority. The Senate, though, will remain under Democrat control. So the US Congress will be divided until the 2024 election and the Biden administration no longer has the numbers to get its legislative programme through without a fight – or at least, negotiation “across the aisle”.

And that can be a problem for US governance – sustainable solutions to major policy issues need both congressional and presidential approval. A failure to provide answers for pressing issues will further depress public opinion about the government and democratic institutions.

From now until January 2024, presidential influence on lawmaking is largely diminished. To become a law, a proposed bill requires first the approval of both chambers and second the signature of the president. If the two chambers are unable to agree on a common version of a bill or if the bill is vetoed by the president, the proposed policy change is not enacted and the status quo prevails. The production of laws therefore needs a higher level of bipartisan support.

Divided government increases the chances of political gridlock and reduces the likelihood that presidential proposals will become law. It raises the chance of a government shutdown and corresponds to fewer acts of significant legislation per congress.

Two factors will make the next two years particularly difficult. The first stems from accelerating levels of polarisation among legislators. The second is the presence of presidential reelection concerns, if Joe Biden decides to run again in two years time.

Polarisation has reduced Congress’s capacity to legislate and, as a result, public policy is unable to adjust to changing economic and demographic circumstances. As the distance between the preferred policy of legislators, less legislation is created and eventually passes Congress. Policy debate is replaced with acts of obstructionism and acts of grandstanding, where politicians simply signal their policy position to their constituents.

Situations that combine polarisation, divided government and reelection motives of presidents reinforce these tendencies. Consider the 112th Congress after the first midterms during Barack Obama’s administration which ran from 2011 to 2013, or the 116th Congress which ran from 2019 to 2021, after the midterms during Donald Trump’s term of office. Like Joe Biden now, Obama and Trump faced a divided government after the midterms and both were up for reelection. The graph below shows that this resulted in particular strong falls in the number of new laws passed (25% for Obama, 22% for Trump).

Author calculations. Data: https://www.govinfo.gov/

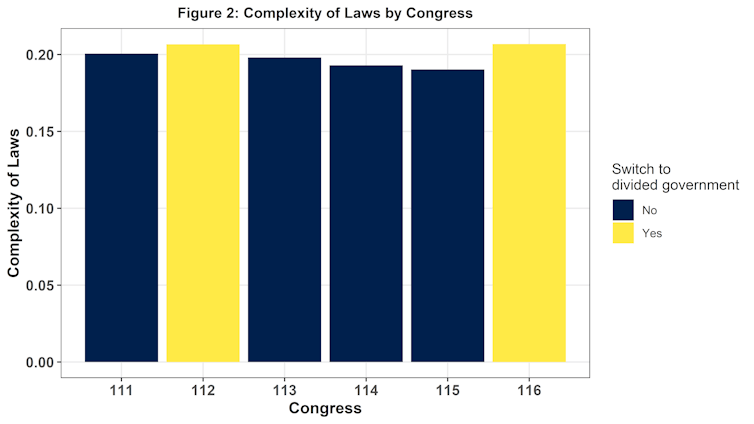

Beyond the quantity of legislation, the shift from unified to divided government during the Obama era also influenced the type of legislation enacted. The laws that passed after the midterms in 2010 were more often related to public goods, such as defence or infrastructure, rather than private legislation. Moreover, the share of bipartisan co-sponsors on passed laws grew from 38% to 47%, while minority party support in voting climbed from below 40% to about 60%. The graph below demonstrates that approved laws became more complex (3% for Obama, 8% for Trump) as they had for example more exemptions built in to attract a degree of bipartisan support.

Author calculations. Data: https://www.govinfo.gov/

Legislative footprint of the next congress

The result of the recent midterms is likely to shape the legislative footprint of the government even more when compared to those historically comparable cases.

This is because of the extent of polarisation between the representatives of the two parties in the US Congress. As this polarisation keeps increasing, we believe that the drop in the number of new laws passed will be even sharper than in the previous cases. Growing polarisation reduces the policy space on which legislators are willing to compromise and thus leads to more gridlock.

This naturally translates into a high chance of government shutdowns as strongly partisan legislators are determined to undermine their opponents’ political agenda regardless of the costs. For example, the upcoming negotiations between Biden and House Republicans over raising the debt limit will be a particularly thorny issue.

Added to that, the democratic majority in the Senate and the possibility of a Biden veto makes the passage of partisan bills proposed by Republicans in the House virtually impossible. But the same thing cuts both ways – and Democrat-sponsored legislation that gets through is unlikely to include progressive social policy proposals on Bidens’ agenda – for example provisions that protect Roe v. Wade or ban assault-weapon sales.

There is also a likelihood that the quality of the legislation might deteriorate. Recent research suggests that excessive legislative activism by either side worsens the quality of laws. As this study investigates a period when congress was substantially less polarised (1973-1989), the currently much higher level and continuing rise of polarisation in the American public creates powerful incentives for legislators to demonstrate their activism to their constituents via the bills they propose. This will limit Congress’s ability to carefully improve submitted legislation.

Phases of divided government with reduced legislative activity have also been associated with positive reform of institutions such as the civil service. But the current environment – with the severe distrust in institutions and politics that prevails – makes such efforts unlikely.

This could become everyone’s problem. The divided Congress is likely to mean a reduced chance of policy agreement on issues such as climate change or the US approach to the Russia-Ukraine war. It’s that serious.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.