The European Space Agency’s (Esa) Gaia mission has just released new data. The Gaia satellite was launched in 2013, with the aim of measuring the precise positions of a billion stars. In addition to measuring the stars’ positions, speeds and brightness, the satellite has collected data on a huge range of other objects.

There’s a lot to make astronomers excited. Here are five of our favourite insights that the data might provide.

1. Secrets of our galaxy’s past and future

Everything in space is moving, and the stars are no exception. The latest release of data contains the largest three-dimensional map of the Milky Way ever produced – showing how the stars in our galaxy are travelling. Previous data included the motions of stars in two dimensions: up-down and left-right (known collectively as stars’ proper motions). But the latest data also shows how quickly stars are moving away from us or towards us, something we call the stars’ radial velocities.

By combining the radial velocity with the proper motions, we can find out how quickly stars are moving in three dimensions as they orbit the Milky Way. This means we now have not only the best map of where the galaxy’s stars are now, but we can track their motions forward to see how things will change, and backward to see how things used to be.

This can tell us things about our galaxy’s history, such as which stars may have come from other galaxies and merged with our own in the past. Radial velocity measurements can also help us find hidden objects, such as planets and brown dwarfs (extremely faint stars with low mass), from the tiny wobbles they cause as they orbit a host star.

2. Details of how stars die

Gaia is not just measuring the stars in our own galaxy, it also measures those in the neighbouring Andromeda galaxy. The data includes something called Gaps: the Gaia Andromeda photometric survey. A photometric survey measures the brightness of stars and how they change over time. With Gaps, Gaia has measured the brightness over time for every star in the direction of the Andromeda galaxy.

That includes 1.2 million stars. Some of those will be foreground stars in the Milky Way that happened to be in the way, but it should include roughly the brightest 1% of stars in the Andromeda galaxy. This will allow us to study the way that the largest, most luminous stars in Andromeda change in brightness, telling us about their evolution and where they are in their life cycles.

This could tell us more about old stars that are reaching the ends of their lives – some of which could go on to produce supernovas (huge explosions) eventually.

3. The truth about the universe’s strange expansion

Quasars, extremely energetic cores of galaxies at the edge of the observable universe, are the most luminous objects in the universe and the most distant objects we can see. And the new data includes measurements of 1.1 million of them. Quasars contain supermassive black holes that are caught in a violent feeding frenzy. In addition to these confirmed quasars, Gaia has found a further 6.6 million quasar candidates.

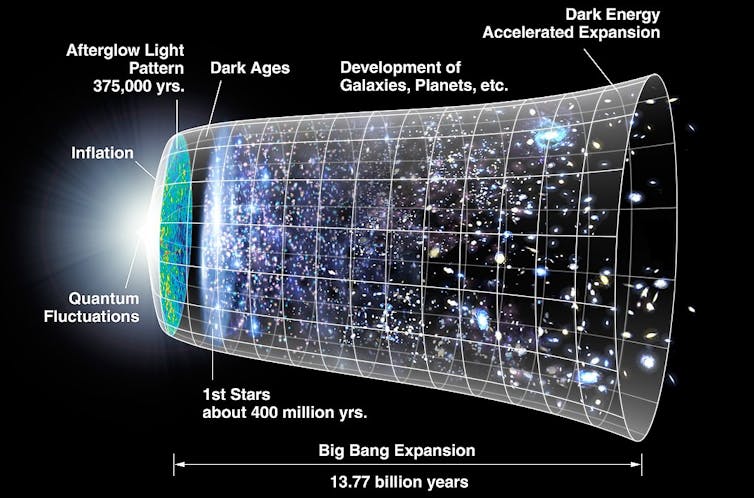

NASA/WMAP

This potentially vastly increases the number of known quasars, and that could be very important because they let us measure the distance to the furthest reaches of the universe. This in turn lets us measure how quickly the universe is expanding. Being able to measure that more accurately is important, because we have two conflicting measurements of the expansion, and we don’t know which one is right – the problem is called “the Hubble tension”.

4. How many asteroids have moons

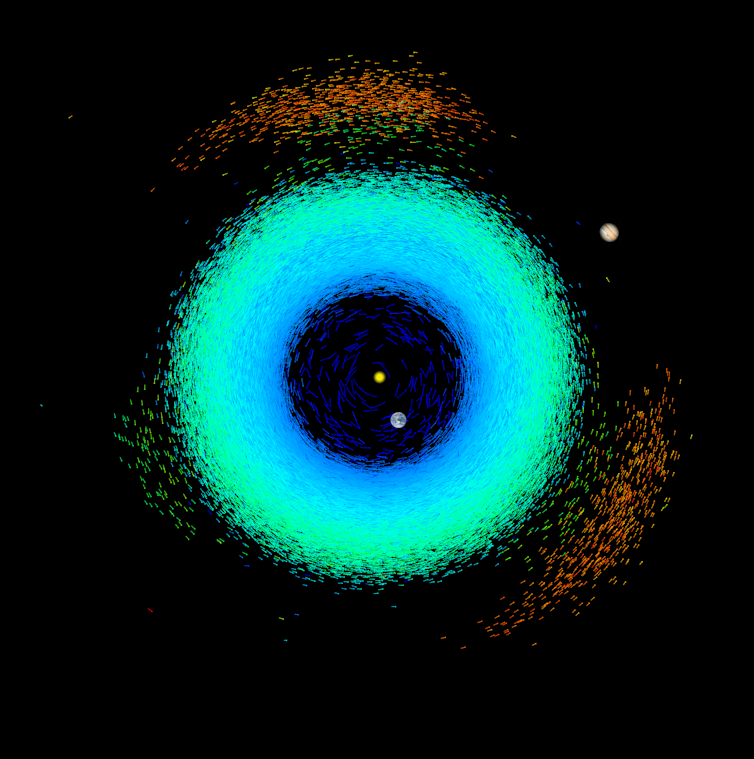

Not everything Gaia is studying is so far from home. The data contains 158,000 objects in our own Solar System. That includes new measurements of 156,000 known asteroids, telling us exactly what paths they follow as they orbit the Sun.

Not only that, but the Gaia team has shown that they are able to find moons orbiting asteroids, based on how the moons make the asteroids wobble. A few hundred asteroids with moons are already known, but Gaia can find asteroid moons even when the moon is too small to see directly. It can also measure the positions of asteroids so accurately that it sees the slight wobble in the position caused by a moon’s gravity. Esa says the latest data contains at least one such new moon, but there could be a lot more.

ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-ND

Gathering better data about asteroids can tell us about the chaos of the early Solar System when the larger planets threw smaller planets and asteroids into new orbits around the Sun and led to the solar system of today.

5. How stars form and operate

Our Sun is a solitary star, but many stars have companions – orbiting each other around a shared centre. The new data contains the first taste of Gaia’s catalogue of such multiple-star systems. This is an initial list, with the full catalogue to come in a later data release, but it already contains 813,000 binary (two-star) systems.

Binary stars can tell us a lot about how stars work and how they are formed. This is especially true for what are called eclipsing binary systems. These are binary systems that happen to be lined up so that the stars pass in front of each other from our point of view. Eclipsing binaries are special because we can take measurements of them to work out all the physical properties of the system, such as the stars’ masses and sizes, and how far away they are. This allows us to learn far more than we could from studying single stars.

This new data will excite astrophysicists around the world, and we can’t wait to get stuck into it to see what we can find. We might have some of these answers in the next few months, while others might take longer.

![]()

Adam McMaster receives funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council, DISCnet, and the Open University Space SRA.

Andrew Norton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.