When it comes to farming, it’s important to start small. There is a lot to learn about growing food, and gradually building up your farm can help your learning curve.

Dallas Robinson knows this well. The new farmer didn’t grow to the scale she planned to this year, partly due to the pandemic, but also because the soil on her farm was compacted, and wouldn’t work for her crop plan. She originally planned to grow on a quarter of an acre, but has instead planted cover crops on a much smaller area. Robinson ended up building some raised beds by hand to be able to start growing vegetables this season.

It isn’t quite what she intended, but she says starting small has been beneficial. It’s let her learn about the pests and soil on her farm before putting the necessary infrastructure in place to scale up. She can monitor and manage how pests affect her crops in a more controlled and less risky environment.

“There are so many things that could go awry when you’re pushing too far,” she says. “I feel really good and confident to [start] small, learn what the land has to tell me and then make informed decisions for the next season.”

Before Robinson started her farm—Harriet Tubman Freedom Farm— in Whitakers, North Carolina, she completed the Farm Beginnings Farmer Training at the Organic Growers School. The program taught her about the business side of operating a farm, and paired her with a farming mentor who gave her someone to consult when she felt overwhelmed. One of the pieces of wisdom her mentor imparted on her was that you should learn how to do one or two things well before you attempt to do 18 different things.

“Starting small is a smart way to hold off on burning out,” she says. “It lets you be kind and gentle to yourself and the crops. If you overwhelm yourself and lose things, that’ll probably lead to negative self-talk.”

The land she is farming on had been a conventional hay farm at one time, and before that saw rotations of cotton and tobacco crops. In her raised beds, Robinson has grown vegetables including carrots, beets, kale, okra, and snap peas. She currently has an informal agreement with one customer, who buys her produce, but hopes to grow to have a 20-member CSA by the fall. She’s planning to grow the gluten-free grain sorghum to sell to local breweries.

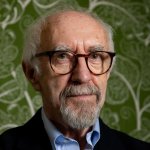

Dallas Robinson, seen here planting seeds, launched her farm in 2019.

Robinson grew up about 15 minutes away from her farm, and spent her high school years lying in the same fields she now works, gazing up at the stars. She didn’t come from a family of farmers, but in college, she started thinking about how she could be a more conscious consumer, which turned into a yearning to grow her own food. She thought it might be nice to grow some herbs on her windowsill or have a garden in her backyard. It wasn’t until she completed a week-long program at Soulfire Farm in New York that she realized she wanted to become a farmer.

She had previously worked in the nonprofit sector in youth development, but got depressed about the thought of working at organizations led by people who she felt were out of touch with those they claimed to serve. “It just seemed like a lot of white people with money who were telling working-class, poor, black and brown people how to use money to better their life. That was upsetting,” she says.

So one day, she just quit without another job lined up. Robinson decided to go take the program at Soulfire after a friend recommended it. She says the program creates a learning environment rooted in African and Indigenous agricultural knowledge. Growing up in the South, near cotton fields where enslaved people once worked, Robinson says she had associated agriculture with pain and trauma. But through the Soulfire program, she learned about how Black farmers made vital contributions to agriculture and the civil rights movement. “It sparked a sense of pride in me,” she says.

Robinson arrived at Soulfire on a Saturday and by the following Wednesday, she had decided she was going to return home to North Carolina to launch Harriet Tubman Freedom Farm.

She named her farm in tribute to Harriet Tubman, as well as civic rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, who founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Mississippi in 1967 to provide a refuge for evicted Black farmers.

One of the barriers Robinson has had to endure in getting her farm started has been going through her local Farm Service Agency (FSA) office to get her farm number. The FSA is the wing of the USDA that facilities loans, and Robinson needs this number to apply for USDA grants and loans. Many Black farmers still have a high level of distrust in FSA offices, which is rooted in the USDA’s history of discriminatory loan practices. Robinson applied for her number back in November 2019 and says she feels like she’s been given the runaround since.

Without the ability to apply for those grants, Robinson has had to pay out of pocket for everything in her first year so far.

“Those institutional places for me are the biggest challenge, because they don’t make me feel good to deal with, and I literally get nothing from them. It slows me down even more,” she says.

The relationship that communities of color in the South have typically had with agriculture have been traumatic and painful. But Robinson hopes a new generation of Black farmers will be able to use the process of growing food as an empowering and healing response to that trauma and racial injustice.

“It’s very freeing to be connected to land and place,” she says.

The post Year One: Start Small appeared first on Modern Farmer.