In the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic in late March, the UN secretary general, António Guterres, issued a call for a global ceasefire. He described it as the most challenging crisis since the second world war.

Three long months later, the UN security council has now unanimously endorsed that call. A new resolution passed on July 1 asks all armed groups to begin a “humanitarian pause” for at least 90 days to enable the delivery of humanitarian assistance and medical evacuations. It also demanded a ceasefire on all conflicts it is currently discussing, such as those in Syria, Yemen and Libya. While welcome, this decision has likely missed the window of opportunity.

The agreement follows protracted diplomatic negotiations which have dismayed officials and observers alike. Some diplomats involved in the negotiations have described their “shame” over the security council’s inaction. By way of comparison, the 193 members of the UN general assembly were able to collectively agree a response in April, well ahead of the 15-member security council. By late June, the call for a global ceasefire had been endorsed by 172 UN member states.

But the security council did not even convene a meeting to discuss the pandemic until April. This led the UN director at Human Rights Watch, Louis Charbonneau, to decry it as “missing in action”.

Politics of WHO

Finding language that the US could accept on the central role of the World Health Organization (WHO) proved to be highly contentious. In the early stages of the pandemic, the US president, Donald Trump, regularly praised China and the WHO for their response to the COVID-19 outbreak. However, as cases escalated in the US this praise quickly turned to condemnation. By mid-April, Trump had announced that the US was suspending funding for the WHO and by late May, Trump had announced a withdrawal from the WHO.

Read more:

World Health Organization: what does it spend its money on?

These moves were reflected in debates inside the security council. China wanted the WHO referenced in any resolution and US diplomats objected. By early May, France and Tunisia had established themselves as co-penholders – meaning they led the negotiations – which gave them both responsibility to find a compromise and influence over the process. They proposed that the reference to the WHO in the draft be replaced by a reference to the “United Nations system, including specialised health agencies”. Despite initially agreeing, the US objected just before the draft was due to be put to a vote, and the negotiations stalled.

Towards the end of June, France and Tunisia instead tried referencing the fact that the security council had “considered” the April general assembly resolution, which in turn had referred to the work of the WHO. This even more opaque reference proved acceptable to the US and the resolution passed unanimously on July 1.

Absence of leadership

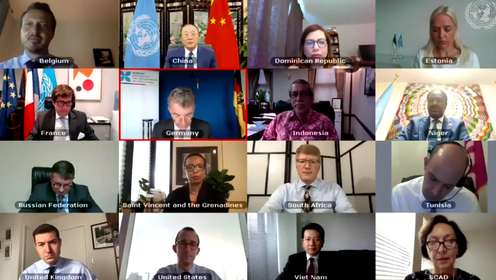

It is clear then that for all the challenges of working via video teleconferences, the real cause of the delay has been the clash between the US and China. As two of the council’s five permanent members, both have the power to individually block decisions with a veto.

Alongside disputes over recognising the role of the WHO they have also fought over language on the origins of the virus. At a time when Trump was referring to COVID-19 as “the Chinese virus”, US diplomats insisted that any resolution must contain reference to the location of the initial outbreak. Later the US switched to demanding language on “transparency” over the origins, in an attempt to embarrass China.

When Guterres first called for the global ceasefire in March, many cynical observers thought it wouldn’t have any real world impact where it matters most in places such as South Sudan, Syria and Yemen. However, armed groups began to unilaterally declare ceasefires in intractable conflicts in Colombia, the Philippines and elsewhere. Saudi Arabia also declared a ceasefire in Yemen due to the pandemic. In fact, by early May the UN indicated that 16 armed groups had unilaterally paused fighting.

Read more:

Colombia hopes for ‘humanitarian’ ceasefire during coronavirus as violence resurges

Yet the security council’s delay in endorsing the idea of a global ceasefire squandered the early window of opportunity to give political weight to the idea. After an initial ceasefire, fighting has already resumed in Yemen and Colombia.

Permanent members of the security council have special responsibilities to show leadership and work constructively, but this has been woefully lacking in this case. The Trump administration, in an election year and facing soaring numbers of COVID-19 infections, has played a spoiler role, driven by a domestic political incentive to scapegoat China and the WHO rather than admits its own failings. Meanwhile China, which held the monthly presidency of the security council in March lacked the political will to coordinate action in America’s place.

The idea of a global “humanitarian pause” in armed conflict endorsed in the new resolution is unprecedented. What it achieves remains to be seen, but if it had immediately followed the secretary general’s plea in March it would have gained more traction. As Richard Gowan, UN director of the International Crisis Group, lamented: “sadly, the council has waited too long”.

![]()

Jess Gifkins has previously been funded by the British Academy for research on the United Nations.

Benedict Docherty has previously received funding from the British International Studies Association. He is a member of the United Nations Association UK.