Technology is a product of human labour. The working class and society can therefore shape its direction. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), long-term technological change has created more employment than it has destroyed, and has pushed overall living standards to new levels, notwithstanding the disruption that it inevitably brings.

What’s more, the ILO concludes in a 2017 report, there’s no “clear sense that this will be otherwise in the foreseeable future”.

The Southern Centre for Inequality Studies has embarked on a research project comparing countries across the global South to explore, through global production networks, the impact of new technology on the future of work and workers. Global production networks have gained increased importance in global production organisation, co-ordination and associated international trade. Using global production networks to anchor an analytical framework enables a focus on the actors involved in the geographically dispersed, multi-scale, multi-dimensional, globalised structures of production and trade.

This includes a focus on workers.

My research focuses on the automotive manufacturing sector – South Africa’s leading manufacturing sector. The research shows that, while technology is indeed a powerful determinant of change, it is important to recognise the role that worker organisation and the state, through its industrial policy, play in shaping the direction of change.

Technological change and job disruption

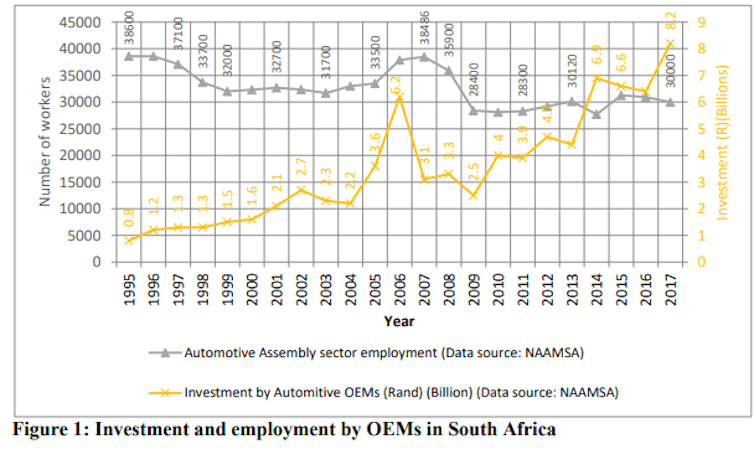

My findings indicate a decline in employment in the final vehicle assembly segment by 8,600 workers, from 38,600 in 1995 to 30,000 in 2017.

During the same period, investment by final vehicle companies, known as original equipment manufacturers, increased from R0.8 billion in 1995 to R8.2 billion in 2017.

Figure 1 below shows the relationship between the investment and employment trends.

The role of the state’s industrial policy through the Motor Industry Development Programme played a key role from September 1995 to December 2012 in attracting increased investment. The plan offered incentives, including import rebate credit certificates. The incentives gave automotive exporting companies reduced import duty, or duty-free imports, on the components that they did not source locally or vehicle models they did not produce in the country.

Increased automation of production, a key part of investment by original equipment manufacturers, wasn’t introduced in isolation. With it came global production systems, new methods of work and ways of co-ordinating production, all more effective than the previous ones.

The changes included rationalisation of vehicle model platforms, in certain instances down to single vehicle platform assembly plant operations.

From January 2013 investment in the automotive manufacturing sector was led by the Automotive Production and Development Programme. This was made up of several incentives. These included a cash grant of 25%–30% of the value of qualifying investment for the vehicle assembly segment and 25%–35% for the components manufacturing segment, payable over three years.

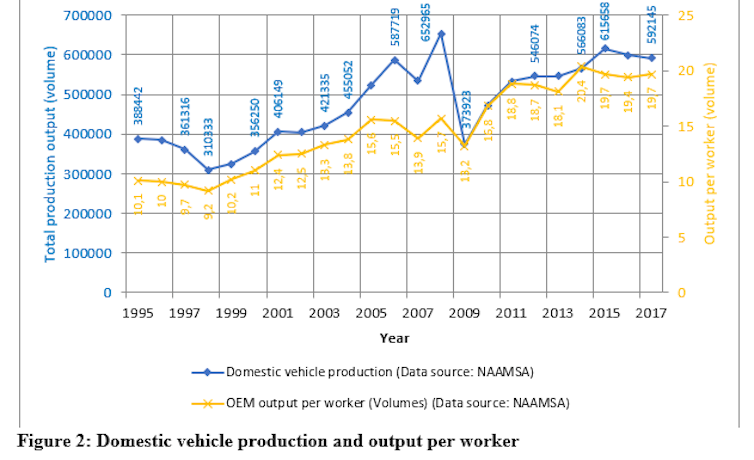

The global economic crisis of 2008 badly affected investment, production and employment in original equipment manufacturers. This is reflected in Figure 1 above, and Figure 2 below.

Yet these manufacturers achieved remarkable productivity from 1995, as a result of technological change and the accompanying work reorganisation and restructuring.

During the period 1995 to 2017, they gained double the capacity of output per worker. Figure 2 below shows their total production volumes divided by their total employment.

The 38,600 workers employed by the manufacturers in 1995 produced 388,442 vehicles, averaging an output of 10 vehicles per worker. The rise in production surpassed half a million, reaching a peak of 652,965 vehicles in 2008. These were produced by a reduced workforce of 35,900 workers – that is the 1995 workforce less 2,700 workers.

The average output per worker increased to about 16 vehicles in 2008. The increase reached double capacity in 2014 from that of 1995, to an average of 20 vehicles per worker. In 2014 the manufacturers’ workforce was reduced to 27,715 – that is the 1995 workforce less 10,885 workers.

The trends presented here reflect the original equipment manufacturers’ specific reality. The research findings show that there are production conditions that, if strong enough, can counteract the reduction in the workforce, and even result in an increase in the workforce, which is important for industrial policy. This is clearly demonstrated by the case of VW, highlighted below.

Worker agency

In 2015, VW decided to invest R6.1 billion, including R564 million for 330 new robots, at its vehicle body construction plant in Uitenhage, Eastern Cape province.

About 600 robots, including the 300 new ones, were expected to complete the structure of each vehicle in a reduced time of one minute and 57 seconds.

The new robots resulted in 40 qualified fitters being declared redundant (not to speak of less skilled workers). VW served the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) with a retrenchment notice. The union challenged VW, resulting in an agreement for the retraining of the fitters as electricians. This paved the way for their jobs to be saved.

VW globally also allocated more production volumes to its Uitenhage plant. This helped save the jobs of (less skilled) production workers that could otherwise have been disrupted by the use of robots. And it resulted in an additional 300 production workers being required.

The plant’s production increased to 133,000 vehicles in 2018, of which 83,000 were for export markets. The 2018 output reflected an increase of 23,000 vehicles from 110,000 in 2017. In 2019 the plant reached its target of 160,000 vehicles, 27,000 more than in 2018.

Conclusion

The decline in overall manufacturers’ employment from 1995 to 2017 in the context of increased capital investment and productivity underlines the necessity of increasing local production to save jobs and create additional employment. This social upgrading through the targeting of employment creation is an important industrial policy consideration and can be linked with the investment incentives given by the state.

The VW case shows that increased production localisation in global production networks can benefit employment in two important ways, despite technological disruption. Firstly, it counteracts retrenchments consequent on the way new technology is adopted. Secondly, it creates additional employment. As the role played by NUMSA at VW indicates, organised labour can shape the direction of new technology and its impact on workers.

![]()

Mohubetswane Mashilo is a post-doctoral fellow with the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies (SCIS) at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. He has previously received funding (research stipend) from the Hans-Böckler Foundation which supported the publication in 2019 of a Working Paper that he produced, titled 'Auto Production in South Africa and Components Manufacturing in Gauteng Province', as part of the project 'Global value chains, economic and social upgrading' at the Berlin School of Economics and Law. He is a member of the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party.