Takashi Images/Shutterstock

Museums and galleries in the UK are opening their doors to the public in July. But reopening will be conditional on their ability to implement safety measures. Social distancing is obviously vital in these institutions, which were often described as overcrowded when life was more normal.

To be able to apply social distancing measures we need to know how many people will be there, what they want to see and how they will navigate from one room to another.

These questions were important to the curators and museum owners even before this period of financial uncertainty for the life of many museums. So much so that, in the summer of 2018, our friends at the British Museum approached us with a very simple question: “can you tell us how our visitors move around the museum and can you do it in an easy and cheap way, yet respecting visitors’ privacy?” In response to that, we launched a project at the Alan Turing Institute called: Listening to the crowd: Data science to understand the British Museum’s visitors.

Following the audio guides

In this project, we relied on data generated by the British Museum’s audio guides – little gadgets that about 5% of visitors rent for £7 if they wish to listen to descriptions of different objects in the museum. To play the relevant audio track, visitors need to dial in a code that is unique to each object. The device not only plays the right track for them but also records the object number and the exact time of the request in its memory. It does this mostly for research and service improvement but also it will email a list of all the visited objects to the visitors at the end of the day, as a nice souvenir.

This digital record also tells us about vistors’ physical location in the museum as we can assume they are most likely to listen to the description of an object while standing close to it.

Claudio Divizia/Shuttertsock

Studying the data of some 40,000 visits, we found the following: most of the visitors spend around 1.5 to three hours visiting the museum. During this time they usually visit between 20 to 45 objects (this only accounts for objects with audio descriptions). Our most important finding was that most of the visitors wander around – they do not necessarily visit all the objects in the same theme nor follow predefined paths (called “tours” – lists of objects that are bundled together by the curators, such as “ancient Egypt” or “highlights”).

Navigating by structures

What actually determines the visitor’s navigation paths more firmly is the physical structure of the museum rather than the thematic distribution of objects, according to our analyses. For instance, the distance of a room from the museum entrance and the number of steps that one needs to climb to get to a room. As such, the siting of the cafe and restrooms can be equally or even more important than the location of the Rosetta Stone.

You are reading this, so there’s a good chance that you’re a museum enthusiast (or a data science enthusiast, or maybe even both), and if so, you might be a bit offended by the last paragraph. You might think that such navigation of museums might be true for the general tourist or “casual” museum-goer, but “seasoned” visitors operate with purpose, knowing what they want to see and usually wanting to see it all.

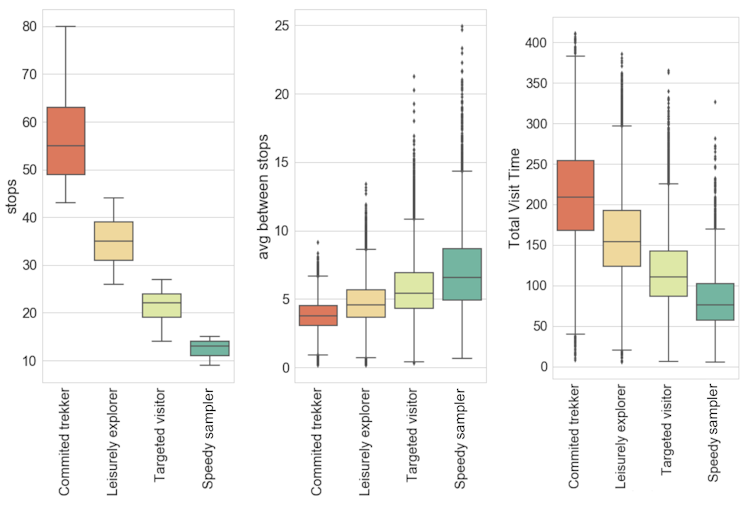

And you’d be right. Apart from studying the general behaviour, we also tried to categorise visitors based on their navigation patterns. Here are the four types of visitors we found:

-

Committed trekkers (22% of visitors): usually solo visitors who spent a lot of time in their visit and see many objects with few or no breaks in between.

-

Leisurely explorers (34% of visitors): often in a group, spending a good amount of time in the museum seeing fewer objects.

-

Targeted visitors (31% of visitors): shorter visits, see fewer objects, spend more time walking across rooms.

-

Speedy samplers (12% of visitors): most likely to be part of a group, spend a lot of time walking between rooms and see very few objects.

Remember though, all the visitors we studied were enthusiastic enough to spend £7 for the audio guide. If we could somehow study all the visitors (with and without audio guide), I’m sure the percentages would be different – heavier towards speedy samplers and lighter on committed trekkers.

Muggleton, Monteath, and Yasseri (2020), Author provided

Safer museum visits

A restricted and controlled visit – the only viable option at the moment – will be better suited to those who fall into the category of committed trekkers. While those who like to explore, take breaks, and have a more leisurely visit, might need to wait a few more weeks. The new nature of visiting could be emphasised in public communications regarding reopening. This is so that those who would normally be leisurely explorers, targeted visitors or speedy samplers know they will, for the time being, have to adopt different viewing behaviours.

Anna Levan/Shutterstock

Considering that the distance from the entrance and upward staircases play such an important role, one idea in reopening could be to have multiple entrances and visits limited to single floors.

Finally, considering that many people see a very tiny number of objects on one visit, it could be a good idea to split the museums into multiple isolated sub-museums. Don’t worry that the ancient Greece objects are spread among multiple rooms and two different floors, very few visitors want to see them all in one visit. Also, this gives visitors the excuse to return.

Reopening museums, it is important to know what type of visitors would be more likely to show up at the door and what type of visits would suit them the best. There is still a lot more to understand about visitors but I hope our work can give some basic insights helping the preparation.

![]()

Taha Yasseri receives funding from the European Commission (Horizon 2020), Google Inc, eHarmony, Oxford University John Fell Fund, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. He is affiliated with the Alan Turing Institute for Data Science and AI.