A parasite commonly found in cats’ faeces might one day help treat cancer. My colleagues and I have discovered that the parasite that causes toxoplasmosis – a condition that can be harmful to pregnant women and those with a suppressed immune system – might be useful at destroying cancer tumours. At least, that’s what our study in mice suggests.

For many years now, researchers have been looking at how they can use the body’s immune system to treat cancer – known as immunotherapy. This is because, alongside protecting us from the harmful effects of bacteria and viruses, our immune system also rids the body of abnormal cells, such as cancer cells. But sometimes these cancerous cells and tumours can develop techniques for evading the body’s immune system, which means that the immune system won’t kill them, and they’ll be allowed to grow and replicate.

One type of immunotherapy is “immune checkpoint blockade therapy”. Our immune system contains a number of so-called “immune checkpoints” that prevent it from destroying healthy cells. But cancer cells can also avoid destruction by taking advantage of this on/off “switch”. The checkpoint can shut down immune cells called T cells and suppress the immune response. This is how some tumours are able to avoid being destroyed by the immune system.

Immune checkpoint blockade therapy works by blocking the checkpoint proteins from binding with their partner proteins and sending the “off” signal. This means that the cancer cells will become “visible” to the T cells, which can then go about destroying the tumour.

While immune checkpoint blockade therapy has shown promise in treating many types of cancer – including lung cancer and melanoma – this type of therapy, and many other immunotherapy treatments, don’t work very well on so-called “cold” tumours. These difficult to treat tumours are surrounded by cells that suppress the body’s immune response, which means immune cells won’t know how to attack it. Types of cancers where cold tumours are common include breast, ovary and prostate cancers.

But our latest research has discovered a method that could improve the treatment of these cold tumours – and it involves using the parasite that causes toxoplasmosis, a relatively common condition that people catch from the faeces of infected cats or infected meat. While it’s typically harmless and often only causes mild flu-like symptoms, it can be serious in pregnant women and those who have a compromised immune system.

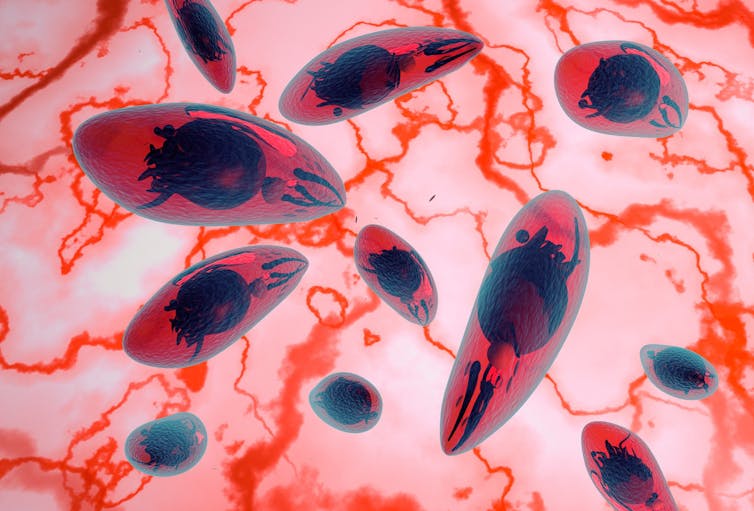

Toxoplasmosis is caused by the Toxoplasma gondii parasite. The reason we chose T. gondii is because it is very infectious and has been shown to infect many species of warm-blood animals – including humans. The pathogen is also very tough, secreting proteins that prevent the body’s immune system from acting – ultimately ensuring its own growth, replication and survival. We figured that all these attributes would allow T. gondii to trigger a strong immune response if administered directly into a tumour in the hope that would be enough for the immune system to kill the cancer.

fotovapl/ Shutterstock

Using the gene-editing technology Crispr, our team engineered a strain of Toxoplasma gondii that lacked the protein that causes disease. We then injected this mutant strain directly into melanoma tumours in mice. We later tested it on colon and lung cancer tumours as well.

We were able to show that injecting the live parasite directly into a cold tumour was able to trigger a strong immune response in mice. We were also able to show that even nearby tumours, which hadn’t been injected, had an increased immune response.

While previous studies have shown that Toxoplasma gondii can be used to treat tumours in mice, our study took this finding one step further. We showed that when this engineered parasite was used alongside immune checkpoint blockade therapy, tumour growth was significantly suppressed. The eight mice given dual therapy in the early stages of melanoma saw their tumours shrink significantly, whereas treatment with only immune checkpoint blockade therapy failed to cause any regression in the injected tumours in mice.

We also showed that the dual treatment was far more effective at not only shrinking tumours but also improving the survival rate of mice when compared with using immune checkpoint blockade therapy alone. All eight mice who only received immune checkpoint blockade therapy died within 39 days – while seven out of eight mice who received the dual treatment were still alive after 60 days. We also saw an increase in a number of different types of helpful immune cells – which ultimately improved the response of melanoma tumours in particular to treatments.

Our research joins a body of evidence that parasites – including the canine tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus – can work against different types of cancer. Bacteria, viruses and bacteriophages (viruses that attack bacteria), are also being trialled as potential cancer treatments.

It’s important to note that this study is only in mice, and it will take many years and many more studies before we know if this therapy works in humans. Nevertheless, it’s an exciting step in the right direction and adds to the growing evidence base that pathogens might be helpful tools in our fight against tough-to-treat cancers.

![]()

Hany Elsheikha does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.