A new study has measured the impact of working during the pandemic on NHS workers’ mental health. It found almost half of critical care staff met thresholds for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety or problem drinking.

The researchers, from King’s College London, surveyed intensive care unit (ICU) and anaesthetic staff in the summer of 2020, following the first wave of COVID-19. At the time, nearly one in seven staff, and around one in five nurses, reported they had experienced thoughts of being better off dead or of hurting themselves in the previous two weeks.

This study serves as a stark reminder of the toll the pandemic has already had on NHS staff. On top of this, it raises questions about the mental health of frontline workers and how they can be supported as cases continue to rise.

The researchers worked with clinical ICU leads from six NHS hospitals in England to circulate an anonymous online survey to staff during June and July 2020. The survey included questionnaires used by clinicians and psychologists to measure levels of PTSD symptoms, depression, anxiety and problem drinking. These are used widely within the NHS to assess whether people should be referred for psychological therapies or other treatments.

Read more:

Nurses report PTSD symptoms due to the pandemic – here’s why

The study looked at 709 staff, with around half nurses, 40% doctors, and the remainder made up of other clinical roles. Around two in every five staff met the threshold for having probable PTSD, one in ten for severe anxiety, and one in 15 with severe depression or problem drinking. Nurses were more likely to experience mental health concerns than doctors.

It is important to note this study only provides a snapshot of mental health among staff who chose to complete the survey during the summer of 2020. We cannot say how long these experiences lasted or whether things have improved or got worse. Nor can we say how representative the participants were of ICU and anaesthetic staff in those hospitals, as these details were not reported.

Why is this important?

These findings provide a window into the mental health impact of the pandemic on those, arguably, closest to the myriad challenges unleashed on the NHS. ICU staff have faced, and continue to face, high mortality rates among their patients. They are providing end-of-life support in an environment where communication and family visiting is often impossible, while also contending with increased concerns for their own wellbeing and that of their families. It is perhaps not surprising this study has uncovered evidence of devastating mental health consequences.

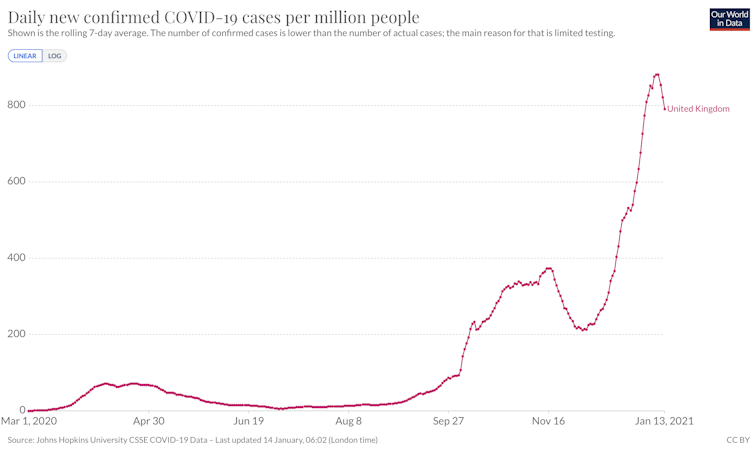

What may be surprising, however, is the scale of the problem. At the time this research was conducted, the pressures of COVID-19 on the NHS were considerably lower than those being faced currently. Yet, as the authors note, the rate of probable PTSD among ICU staff in this study, around 40%, was over double those previously reported among military veterans. Given the trajectory of the pandemic, it seems likely the situation has only deteriorated.

OurWorldInData, CC BY

Such high levels of probable PTSD, anxiety and depression raise concerns for the safety of both staff and patients given the associations between healthcare staff’s mental wellbeing, burnout and patient safety.

Furthermore, given the large body of evidence linking psychological wellbeing to physical wellbeing, including in the context of viral infections, as well as the effectiveness of vaccines, failing to protect frontline staff’s mental health may only exacerbate the existing crisis.

While these findings are important and will rightly inspire interest, it is important to reflect on what this study cannot tell us.

It cannot, for example, tell us which ICU staff are most at risk of poor mental health or how to best help them. While nurses showed poorer mental health than doctors, this may be an age and gender effect explained by the greater proportion of young females among UK ICU nurses, a group we know from other studies during this pandemic are the most likely to be suffering poor mental health.

It is also unclear how many of these staff were ICU-trained staff or those from other specialities deployed to support ICUs during the pandemic. Staff from other specialities might be expected to experience even greater mental health difficulties given their relative inexperience of managing patients in an ICU.

What more needs to be done?

The current work suggests the prevalence of mental health difficulties among ICU staff was already high, even before we entered the current and most devastating phase of the pandemic.

There is, therefore, an urgent need for trusts to provide a suite of measures to support the mental wellbeing of staff, and for these to be both preventative and curative. Also, as the pressures of COVID-19 have not been restricted to ICUs, it is imperative that the effects on non-ICU staff are also considered.

Finally, we should strive to understand the personal, social and contextual factors that have enabled almost half of all staff to remain resilient in the face of the pandemic. Among these people, we may find new ways of supporting NHS staff.

Before COVID-19 the NHS had over 100,000 vacancies. The number of hospital beds was in decline, having halved in the preceding 30 years, and our number of critical care beds per capita was far below the average for Europe as a whole. A mental health crisis among NHS staff will compound these issues, with potentially devastating consequences for all aspects of healthcare long into the future.

![]()

Kieran Ayling receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health.

Kavita Vedhara is a member of the scientific advisory board of the Fertility Health Group