Shutterstock

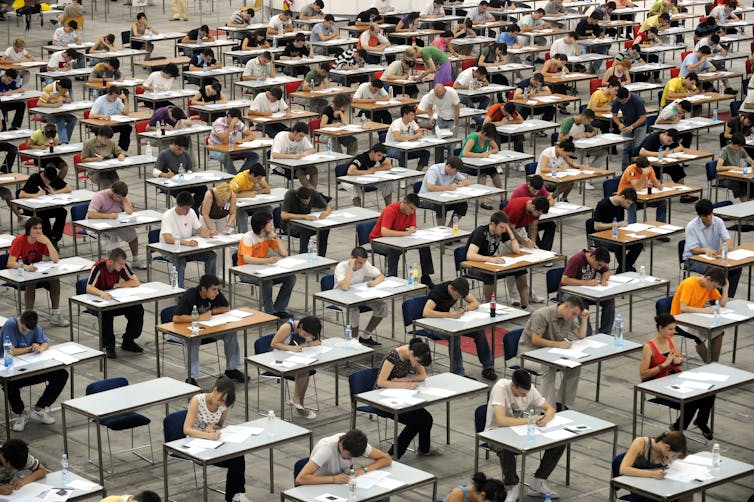

Anger and confusion followed the release of this year’s Scottish Qualification Agency (SQA) results, the first of the UK nations to publish school results in the aftermath of COVID-19. About one quarter of teacher-recommended grades were changed: most were downgraded, and this was more likely to happen to pupils in poorer areas. This controversy shows that assessment is not neutral: the system of assessment can benefit some groups of students over others and it requires more than technical processes to ensure justice.

While the Scottish government initially defended the results in the name of maintaining standards, they are right to have now recognised that the approach was too technocratic and broke an essential link between what a student has actually done and the mark they receive – which is the genuine meaning of standards. But this problem is not new to this year’s results.

How assessment works

To understand the strengths and weaknesses in the initial SQA approach we need to compare two different approaches to assessment: norm-based and criteria-based. In criteria-based assessment students’ work is evaluated against specific criteria, such as strength of argument, quality of research or clarity of expression. All students are assessed against the same criteria.

The number of As in a year could go down or up, and going up does not necessarily mean the dreaded “grade inflation – where increases in grades are assumed to mean a reduction in standards. Large variation may be unlikely but not impossible – and variation itself should not be seen as a problem. Criteria-based marking is considered just because it retains a link between what a student has actually done, the marking criteria and the mark they receive.

In norm-based assessment, results depend on comparing students in a form of ranking: the higher your ranking, the higher your mark. Exactly the same piece of work could get an A one year and a C another year, depending on the performance of other students, rather than the quality of the work. In the past there was even a fixed percentage of grades each year.

Assessment in 2020

When final exams this year were cancelled, the SQA asked teachers to make judgements based on a range of sources, including prelim exams, class work, practical work, in-class tests and homework. The aim was to get a broad sense of students’ level of learning.

As long as teachers had common criteria for grade levels, this system had many advantages compared with traditional exams. Teachers were also encouraged to talk with one another about their judgements. This form of joint decision-making using criteria contributes to more just and more robust assessment outcomes.

Shutterstock

The controversy relates to something called “moderation” which is intended to check on quality, standards and consistency, adjusting the initial scores of a wide range of markers.

Problems arise when moderation tries to standardise large groups, such as across a whole country, and does so using norm-based approaches, thus undermining the principles of criteria-based marking. Norm-based moderation is administratively convenient but educationally unsound.

It was through moderation that one quarter of students had their marks changed. The Scottish government initially said that without moderation the extent of increase in grades among disadvantaged students would not be considered credible. To moderate results, the SQA used a range of mechanisms, including comparing this year’s students with average performance in their school over previous years. If the variation was considered too large, results were adjusted down using rankings provided by teachers.

Once a student’s grade is decided with reference to their peers or previous students, this is norm-based marking. It breaks the fundamental link between what a student has actually done, the criteria and the mark they deserve.

System based on standards

Versions of norm-based moderation have been going on for decades, in all parts of the UK and under governments of all persuasions.

The SQA does have several sophisticated procedures to lessen unfairness, but the problem remains that the system long associated with protecting standards in the UK uses norm-based expectations. Pressure to do so often comes from universities and employers who want to use grades to make selection between students easier: but is this the purpose of schooling or assessment of student learning?

Shutterstock

The approach initially taken this year was also flawed because the SQA was not comparing like with like. Previous year results were based heavily on a final, traditional exam, which is very different to the broad range of items teachers used to make judgements this year. There is evidence that traditional approaches to education and assessment disadvantage working class students. The increase in poorer students’ pre-moderated marks may not lack credibility – but it may show that the assessment approaches we have put faith in for years have been unjust and themselves not credible.

Taking the lead from the SQA’s recommended approach of judgements made through professional discussions, effort should have been made to go back to schools: any moderation can only be based on evidence of different interpretation of criteria.

It would be time-consuming for teachers and SQA staff, but consider the ultimate benefits in terms of rigorous, credible and just assessment that will shape a generation’s futures. The most important thing is that we do not for any reason break the link between a student’s work, the criteria and their mark.

The controversy, and the Scottish government’s change of heart, reinforce the need to explore the foundations of what we call standards so that defending them is not simply a justification for the status-quo. This year’s results in Scotland are not necessarily more or less fair than previous years, but probably unfair in new ways: COVID-19 has shone a light on the larger problem of justice and assessment.

![]()

Jan McArthur receives funding from Economic and Social Research Council, the Office for Students and Research England (grant reference: ES/M010082/1) and National Research Foundation, South Africa (grant reference: 105856).