Dinosaurs were the dominant group of animals on Earth for over 150 million years. Long-necked, plant-eating sauropods such as Brontosaurus, Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus are probably among the most famous dinosaurs, in part thanks to their huge size and strange body shape (consisting of a long neck, long tail, round body and columnar limbs). Some of the largest sauropods measured up to 37 metres long.

But less well known is that they descended from much smaller, two-legged, omnivorous or plant-eating creatures called sauropodomorphs. My colleagues and I recently identified a new dinosaur species that represents the oldest known evolutionary step between early sauropodomorphs and sauropods, from about 225 million years ago.

The sauropodomorphs were among the first dinosaurs to exist during the late Triassic period, from about 230 million years ago. During this time, dinosaurs weren’t yet the dominant group of animals on Earth and had to share the world with, among others, crocodile-like reptiles called phytosaurs and mammal-like reptiles, such as Morganucodon.

Towards the end of the Triassic and in the earliest Jurassic, environmental changes led to the evolution of larger, more immediate predecessors of sauropods. These dinosaurs were larger, had longer necks, ate only plants and, more importantly, walked on all fours due to their size. These transitional species include Pulanesaura from around 190 million years ago in what is now South Africa, and Leonerasaurus from a similar time in what is now South America.

Our new dinosaur, which we have named Schleitheimia, falls into this category. Some of its bones were first found in Switzerland as early as 1915. Others had been found in Hallau, near Zurich, in the 1940s, and others from the same geological layer had been discovered in Schleitheim, also near Zurich, in the 1950s. But for years, these fossils were thought to belong to an earlier, sauropodomorph species.

In 1986, palaeontologist Peter Galton identified this set of fossilised dinosaur remains, kept at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, as belonging to a common sauropodomorph known as Plateosaurus. Plateosaurus had quite a long neck, but did not walk on all fours all the time.

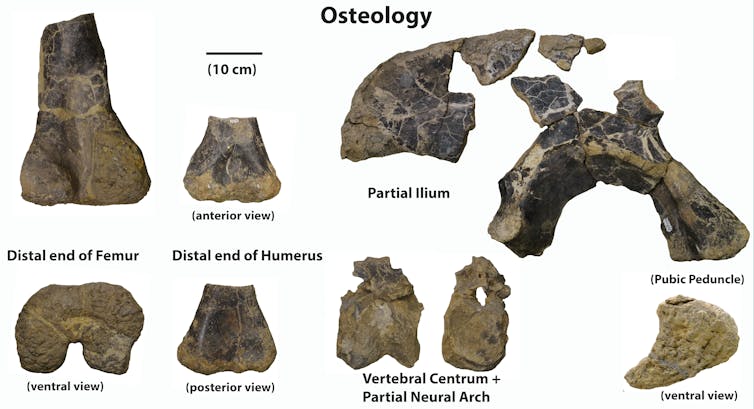

However, when Munich palaeontologist Oliver Rauhut examined the bones more recently, he noticed odd features on them, which made it impossible for them to belong to Plateosaurus. So in 2015, he and I visited the Zurich Palaeontological Museum and examined the bones thoroughly. We discovered several sauropod-like adaptations on the dorsal vertebrae (backbones), the femur (leg bone) and the pelvic or hip area.

University of Utrecht, Author provided

All these adaptations suggest the dinosaur was heavier and mainly walked on all fours, so it couldn’t be a Plateosaurus. It had to be something else, and indeed, it turned out to be something new.

We ran a phylogenetic analysis, which compares anatomical traits between different animals and calculates how many evolutionary steps are necessary to make them related to one another. This suggested our new dinosaur, Schleitheimia, was actually an intermediate type between sauropodomorphs such as Plateosaurus and true sauropods such as Brontosaurus.

Oldest transitional species

This makes Schleitheimia special in two ways. First, it is a lot older than the other known transitional types of dinosaur between sauropodomorphs and sauropods. And second, it is the first transitional form known from Europe.

What is even more interesting, is that some of the Schleitheimia fossils were found in the same quarry as an actual Plateosaurus. This means that both the ancestral sauropodomorphs and the transitional forms shared the same habitat for a time. Eventually, however, the true sauropods took over the environment.

Perhaps their size and longer necks helped them forage for food, we aren’t sure. But what we do know is that by the early Jurassic period, around 170 million years ago, sauropods were already living around the world from China to Argentina. Schleitheimia provides one more piece of the puzzle as to what happened in the sauropods’ very early history on Earth.

The next steps here will be to look at other material from roughly the same age from Switzerland. The original, historic pit where Schleitheimia was found, has been reopened to see whether there is more material.

We want to know if there were more intermediate sauropodiforms around, such as Schleitheimia, or just more sauropodomorphs? And how did the early sauropods diversify and spread out in the early Jurassic? The fact that we can still find new dinosaur species, even in historical museum collections, gives us hope of answering these questions.

![]()

Femke Holwerda does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.