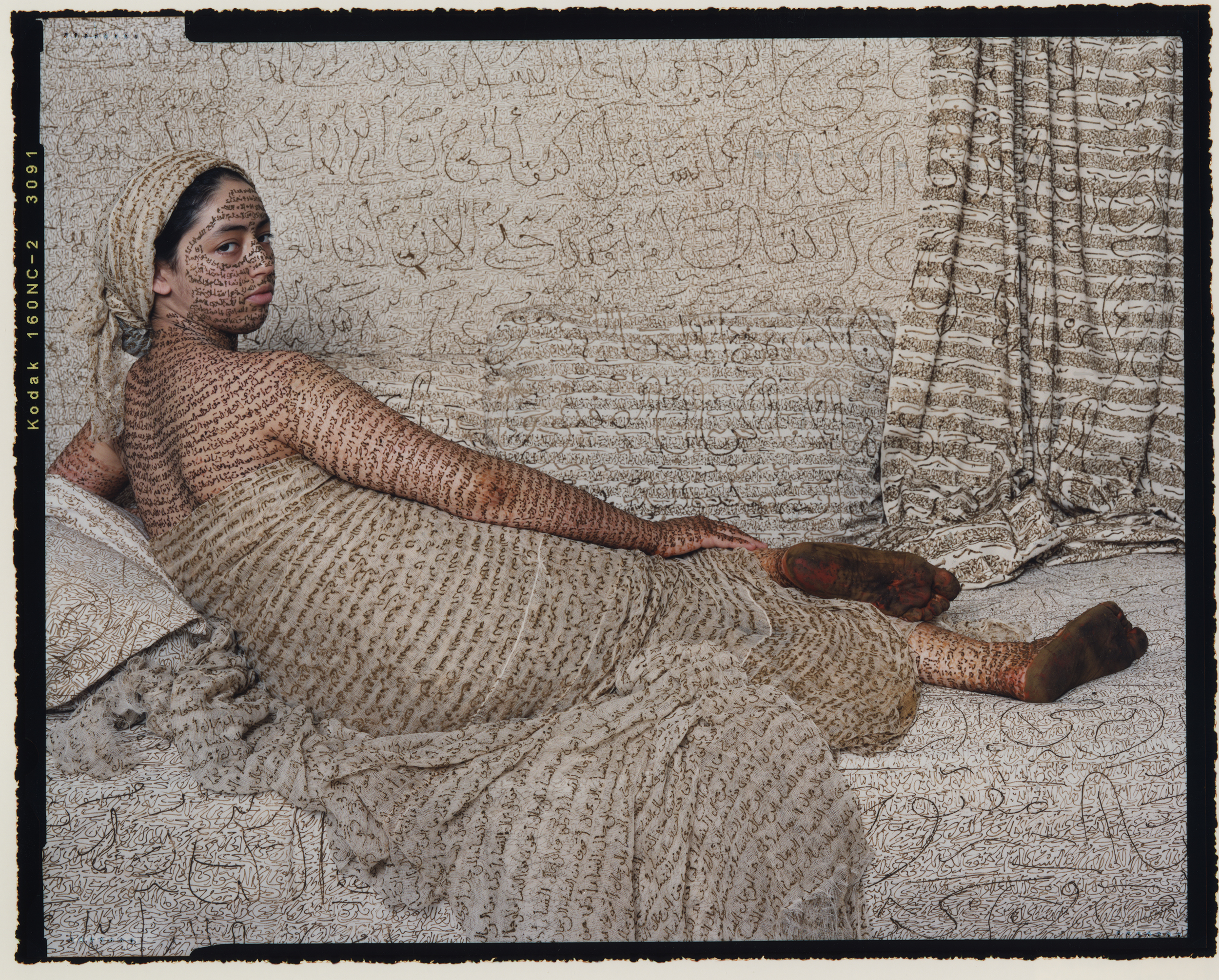

Lalla Essaydi, Harem #2, 2009. 71 × 88 in 180.4 × 223.5 cm.

Moroccan artist Lalla Essaydi, 64, is well known for her dazzling, multidimensional staged photographs, which in spite of their simplicity, masterfully capture and challenge the complexities of social structures, women’s identities and cultural traditions.

Essaydi‘s artworks not only reinvent visual traditions; they also “invoke the western fascination with the odalisque, the veil, and, of course, the harem, as expressed in Orientalist painting.”

“My work speaks primarily in terms of Moroccan identity, but visual identifiers such as the veil, harem, ornate ornamentation, and sumptuous color also resonate with other regions in the Muslim and Arabic worlds where the place of women has historically been marked by limited expression and constrained individuality,” Essaydi said in an interview with Global Voices.

Raised in Morocco, Essaydi has lived in Saudi Arabia and France and is currently based in Boston. She has exhibited at the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., the Art Institute of Chicago, the Fries Museum in the Netherlands, among others.

Essaydi is a poet of architecture, the female body, and color. Where letters overwhelm her composition, the bold presence of women and the veiled apprehension in their eyes disrupt all equations of beauty.

Excerpts from the interview follow.

Moroccan artist, Lalla Essaydi. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Omid Memarian: Over the past two decades you have been creating striking artworks that conceptually challenge social structures and comment on power and authority. How did you find and develop this visual language?

Laila Essaydi: My approach to art in general, and my relation to Islamic art in particular, is deeply rooted in my personal experience. As a Moroccan-born artist who has lived in New York, Boston, and Marrakesh and who travels frequently to the Arab world, I have become deeply aware of how the cultures of the “Orient” and “Occident” view one another. In particular, I have become increasingly aware of the impact of the Western gaze on Arab culture.

Although Orientalism most often suggests a 19th-century European vision of the East, as a set of assumptions it lives on today: both in the gaze of the West and in the way Arab societies continue to internalize and respond to that gaze. In its early form, Orientalism was a literal “vision,” finding expression in the work of Western painters who traveled to the “exotic” East in search of cultures more colorful than their own, I have used it as a point of departure in much of my own work—in both painting and photography.

The imagery I found in Orientalist painting has resonated with me in tricky ways and ultimately helped me situate my own experience in a powerful visual language.

In my photography, I explore this space, whether mental or physical, and interrogate its role in gender identity-making, while engaging with centuries of cultural heritage and artistic practices. For instance, my images of women, embedded in Islamic architecture, recognize and represent an alternative to similar spaces, as imagined for women, in painting and photography, from within the Arab and Muslim worlds. My fusion of calligraphy (a sacred art traditionally reserved for men) and henna (an adornment worn and applied only by women) similarly reproduces artistic traditions and practices common in everyday life in Islamic cultures while transgressing gender roles and the boundaries between private and public spaces.

Lalla Essaydi, Harem #1, 2009

OM: You were born and raised in Morocco, spent 19 years in Saudi Arabia, moved to Paris and studied there and finally landed in the U.S., studied, and lived there. How has this geographical path impacted your art, your perception of women, and their presence in your photos?

LE: My work is inspired by personal history. The many territories that converge in my work are not only geographical ones but territories of the imagination, shaped, above all, by childhood and memory—by these invisible influences. My work cannot be reduced to Orientalist discourse. Orientalism has given me a lens through which to focus on the converging territories of my work and through which to see more clearly the influence of Western imagination in the Eastern ways of conceptualizing the self. At a more personal level, my creative practice is a means through which I can reinvent and position myself in different times and cultural contexts.

At the same time, I also celebrate the cultural richness of Morocco, the Middle East and North African countries. Although I tend to think of my work as, first and foremost, being about the experience of women, I would say that these elements are also significant. They do not happen incidentally but are part of the inherent qualities that I bring to my vision and my work.

Lalla Essaydi, Bullets Revisited #37, 2014.

OM: How did earning a BFA and MFA from Tufts University and the School of Museum of Fine Art contribute to your career and artistic transformation? Was the education something you expected?

LE: I enrolled in the Museum School because I wanted to return to Morocco and be able to pursue my hobby with greater knowledge and skill. Instead, I found my life’s work.

I learned that some of the most important things in our lives happen unexpectedly. We take a class in painting and discover an entire new world at our fingertips: waiting to be grasped. We take a class in painting and find art history, and installation, photography and so much more. We look for a glass of water and find an ocean, calling to us. And we answer the call.

I never dreamed I would spend seven years in this environment, immersing myself in everything the School had to offer, and learning more than I had ever imagined was possible.

This was, and is, a school of artists, designed by and for artists: where students are free to choose what they want to learn. It only offers elective modules, and there are no mandatory classes. When we realize the riches that are available, we want to absorb everything.

At first I was overwhelmed. I was one of those students who roamed the corridors of the School late at night, peering into the empty rooms, with their silent trappings of whatever medium was taught there.

Eventually, the School taught me a second lesson. With all these opportunities and this great array of artistic riches, with this enormous freedom to choose, comes responsibility.

Responsibility first means discipline, and setting priorities, followed by learning new skills and techniques. And then comes self-direction, as we learn and understand new ways of thinking about art, and the ambition to do something important with our lives.

My career offered me something else, something I did not expect. This very public environment offered me a private space, something I had never had at home. It offered me a space where I was free to express my thoughts in private, without the inhibiting knowledge that they were available for all to see. This enabled me to explore and bring to the fore aspects of my own interior life I hadn’t even known were there.

While I knew that creating art is an intensely personal experience, I also learned that it happens only with the help of a lot of gifted and dedicated people: people who teach and guide, people who encourage and nurture, people who inspire you to keep reaching to create what is excellent and beautiful and true. You can tell, I loved the School.

Lalla Essaydi. Les Femmes du Maroc: La Grande Odalisque, 2008

OM: Women and their private space in the Arab world are central to your series “Harem” and other work. Where did this curiosity and focus come from and sow has it changed over time?

LE: My work reaches beyond Islamic culture as it also invokes the Western fascination with the odalisque, the veil, and, of course, the harem as it is expressed in Orientalist painting. Orientalism has long been a source of fascination for me. My background in art is in painting, and it is as a painter that I began my investigation into Orientalism. My study led me to a much deeper understanding of the painting space so beautifully addressed by Orientalist painters in thrall to Arab décor. From its terrific prominence in these paintings, this décor made me keenly aware of the importance of interior space in Arab/Islamic culture. And finally, of course, I became aware of the patterns of cultural domination and predatory sexual fantasy encoded in Orientalist painting.

Memarian: Your artworks incorporate multiple layers, a beautiful and colorful layer on the outside, and inviting mixed layers of calligraphy, henna, ceramic, and also models. The latter rests on the edge of cliché, but it also creates a lively and mystical visual labyrinth. What is it like to navigate this fine line?

Essaydi: It is important for me that my work be beautiful. While it is received very differently in Western and Arab contexts, its aesthetic is appreciated in both. More critical for me, however, is that the photographs achieve a balance between their political, historical and aesthetic content, as well as make a statement on art.

But the fact that I have sometimes been critiqued for, on the one hand, perpetuating expectations and stereotypes rather than refuting them and, on the other, for exposing that which should remain private, indicates that responses to my work are highly subjective, context-specific and likely culturally informed. Tempered by the ambiguity of the work’s literal meaning, perhaps defaulting to the most accessible and intuitive reaction: perception of the stereotype. Nevertheless, with deliberate subtlety, my work introduces alternative, challenging perspectives on canonical 19th-century Orientalist paintings. As a female artist from the regions depicted, mine is an historically repressed voice that “complicates any neat framing of the canon.” Drawing on similar visual devices, I try to engage it in an unfamiliar and uncomfortable dialogue, and re-situates the Orientalist genre in the history of art.

Harem Revisited #34, 2012

OM: In a 2012 interview you said that your models “see themselves as part of a small feminist movement.” While “freedom” is one of your main concerns, and many of your works seem to reconstruct traditions, how does this contradictory formula have such a liberating result?

LE: My work may seem to “reconstruct traditions,” but in fact I am trying to create a new understanding.

The liberating result comes because in many ways, performance is an intrinsic element of my photographs, evident in the figures’ careful composition, in the physical act of writing and, more importantly, in the intensity of the sitters’ embodied presence that also renders them subjects rather than objects.

Through writing, I lay bare personal thoughts, memory, and experiences that belong to me and the women featured as individuals within a broader narrative. Though my work speaks primarily in terms of Moroccan identity, visual identifiers such as the veil, harem, ornate ornamentation, and sumptuous color also resonate with other regions in the Muslim and Arabic worlds where the place of women has historically been marked by limited expression and constrained individuality.

While my work evokes the region’s traditional aesthetics and social practices, I insert a dimension that complicates them: a personal narrative that takes form in the written word. In volumes upon volumes of text, these women voice critical reflections on and interrogations of memories, all captured within the space of my photographs. At the same time, I write about historical representations of Moroccan, Arabic, Muslim, and African women. To understand my work, then, one must examine long-standing preconceptions held by diverse peoples over time, as well as by myself.

Lalla Essaydi, Bullets, Jackson Fine Art. February 3 – April 15, 2017