A new census, the first of its kind, of all local councils in the UK reveals significant under-representation of ethnic minorities, with some councils having fewer ethnic minority councillors than would be expected given their highly diverse local populations.

An institutional disadvantage in local government can perpetuate wider ethnic disadvantages – and scrutiny and pressure must be extended to this level of government to improve representation. The Black Lives Matter marches, the Windrush Review finding of institutional failures in the Home Office’s “hostile environment” policy, and the discovery that ethnic minority people are at higher risk of death from COVID-19, keeps issues of racial disadvantage at the top of the news agenda. Yet, we still lack a clear view of what to do about it.

One of the strategies must be to make sure ethnic minorities are fairly represented in decision-making bodies. The importance of this local level is underlined by the recent lockdown of ethnically diverse Leicester and the inclusion of many diverse areas on a list of future possible local lockdowns.

In national politics, Britain has made progress on ethnic minority representation in the last ten years. From a small handful of ethnic minority MPs there are now more than 60 – and on both sides of the houses of parliament. From all-white government, Britain has progressed to the most diverse cabinet in history, with two out of the three top jobs held by minority politicians. Despite the remaining shortfall, at the national level the intense scrutiny since at least 2010 has helped to improve things – and quickly.

What is now needed is this same intense scrutiny of local government. Before now, we knew virtually nothing about the representation of ethnic minorities at the local level, even though this arena carries so much impact on the lives of minorities. From planning, transport, education, housing and green spaces that affect everyone, to more specific decisions to do with grants for local organisations and powers over local businesses – including licences, enforcement of trading standards and business support – local authorities can play a role in perpetuating ethnic disadvantages, or could be used to address them.

Minority report

Our study found that 7% of local councillors are of ethnic minority origin, compared to 10% of MPs. This is largely explained by the uneven distribution of ethnic minorities around the UK, as numbers of ethnic minority councillors are higher in ethnically diverse areas. However, we also identified many diverse areas such as Manchester, Reading and some London boroughs, that have a significant shortfall.

Author provided

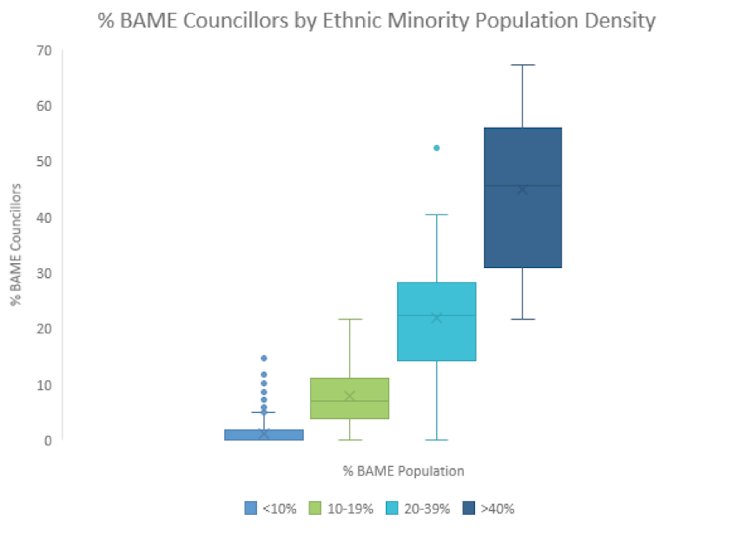

A significant number of the areas where people with ethnic minority origins constitute 40% or more of local residents, have fewer non-white councillors than they should, with a small number having a shortfall of minority councillors of between 10-25% (see Figure 1).

Maria Sobolewska/Neema Begum, Author provided

We conclude that the effort that political parties have made to increase their diversity at a more visible national level – including by placing ethnic minority parliamentary candidates in safe seats – has not been replicated at the local level.

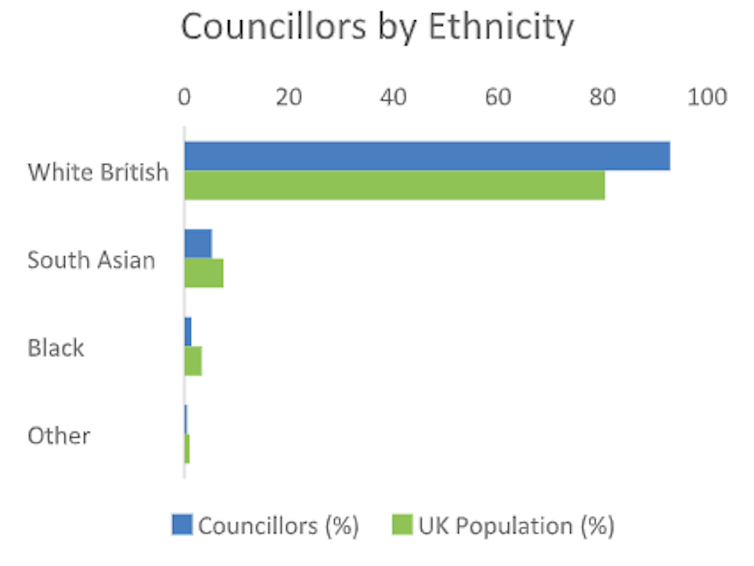

There are also disparities between different ethnicities and, within this, gender. Most ethnic minority councillors are of South Asian background, whereas people of black background are less well represented (see Figure 2).

Maria Sobolewska/Neema Begum, Author provided

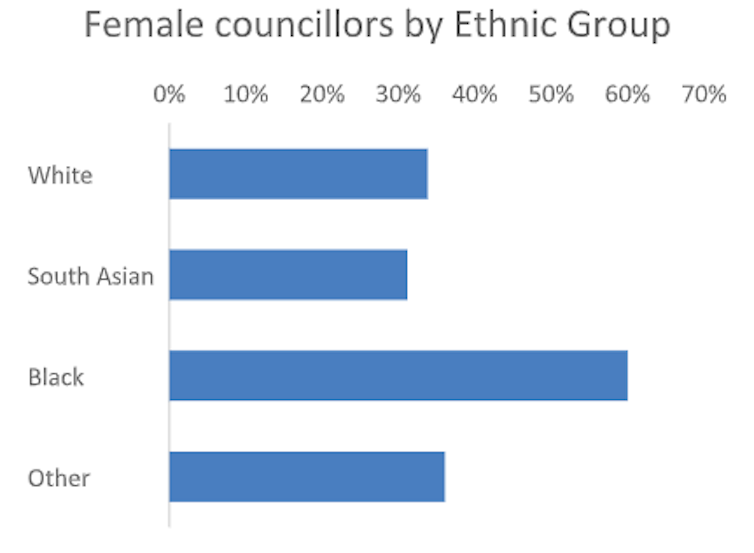

Most South Asian councillors are men, with South Asian women most underrepresented among all women. Conversely, among black councillors, it is men who are the least well represented, as 60% are women (see Figure 3).

Maria Sobolewska/Neema Begum, Author provided

Most ethnic minority councillors represent the Labour Party, perhaps unsurprisingly given the Labour advantage among ethnic minority voters. While the Conservatives have increased their share of ethnic minority MPs, particularly of South Asian background, we are yet to see a similar increase at the local level, again highlighting the lack of a similar push to diversify at this less visible and less scrutinised level of government.

Our study improves on previous efforts, which have been either a census of a selection of local authorities (either in London or those that were deemed particularly ethnically diverse), or were based on surveys with relatively low response rates (Local Government Association biennial surveys). We covered not only all local authorities in England, but also included these in the devolved nations. But the effort and time involved in collecting and coding data on individual councillors is often prohibitive. This could be entirely avoided if the government chose to enact and extend to local government section 106 of the 2010 Equality Act, which puts a duty on the political parties to collect and report equality data of their candidates.

The government has been called on before to enact this section, by the Equality and Human Rights Commission and the pressure now should be reapplied, given the momentum of the anti-racist movement in the UK. Local councils could also be required to publish data on diversity just as the House of Commons now does routinely.

This kind of scrutiny is necessary to keep up the pressure on political parties to improve representation at the local level, and thus ensure ethnic minorities have the power to improve their lives, and their opportunities as active participants in an important political institution.

![]()

Maria Sobolewska receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

Neema Begum receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council.