Taiwan and Iceland have won praise for their effective responses to the coronavirus pandemic. They are among a group of countries which adopted a cooperative strategy early on in the pandemic, bringing together multiple organisations to tackle the challenges in containing COVID-19.

A cooperative strategy is when organisations try to achieve their goals through cooperation with other organisations. Our own recent synthesis of research explains the attraction of this approach. It can allow public authorities or companies to speed up their response to new challenges by partnering with other organisations which have complementary resources and expertise.

While other countries, including South Korea and Germany, have deployed a cooperative approach, it’s been a key part of both Taiwan and Iceland’s response to the pandemic.

Taiwan’s model

Taiwan’s handling of COVID-19 has been exemplary. As of June 29, Taiwan, with a population of 23.8 million, has recorded only seven deaths linked to the virus, with 447 confirmed cases – 435 of which had fully recovered.

The Taiwanese government acted quickly to control its borders. It activated a Central Epidemic Command Centre (CECC) on January 20 to coordinate cooperation across different government ministries and agencies, and between government and businesses. The CECC also coordinates big data analytics, testing, quarantine and contact tracing.

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Administration and National Immigration Agency worked together to identify suspected cases for COVID-19 testing, integrating their databases of citizens’ medical and travel history. Since late March, all new arrivals must quarantine for 14 days.

CECC also partnered with police agencies, local officials and telecom companies to enforce quarantine with the support of mobile phone tracking. Local officials would call quarantined citizens to ask about their health and bring them basic daily supplies if required. Along with a 24-hour helpline, Taiwan’s Center for Disease Control collaborated with two tech companies – HTC and LINE) – to create a chatbot which allowed people to report their health status and get advice about the virus.

Taiwan can now test about 5,800 samples a day through a cooperative network of public and private testing centres and certified laboratories.

To avoid the panic buying of face masks, the government rationed their distribution and ramped up production. In February, the government partnered with the Machine Tool & Accessory Builders’ Association and manufacturers, investing in new machinery to produce surgical face masks. In return, manufacturers have to sell the masks back to the government at an agreed price.

This effective government-led cooperative strategy resulted in the establishment of 60 production lines in 25 days, something which would normally have taken several months. More production lines have been added, and Taiwan now can produce about 20 million masks a day.

The public can interact with the government on vTaiwan, a virtual democracy platform for open discussion to build consensus on policy solutions. A face mask map app grew out of a suggestion on vTaiwan and now provides real-time information on stock availiability. The app was developed through collaboration between the Digital Ministry and a group of entrepreneurs and hacktivists.

Iceland’s strategy

Iceland provides another example of a country which used a cooperative strategy to manage the pandemic. As of June 29, Iceland had recorded 10 deaths and 1,838 confirmed COVID-19 infections, of which 1,816 have fully recovered. Its success can be explained by the government’s quick action in activating the National Crisis Coordination Center on January 31 to coordinate the country’s response to COVID-19 through mass testing, quarantine and tracing close contacts of infected citizens.

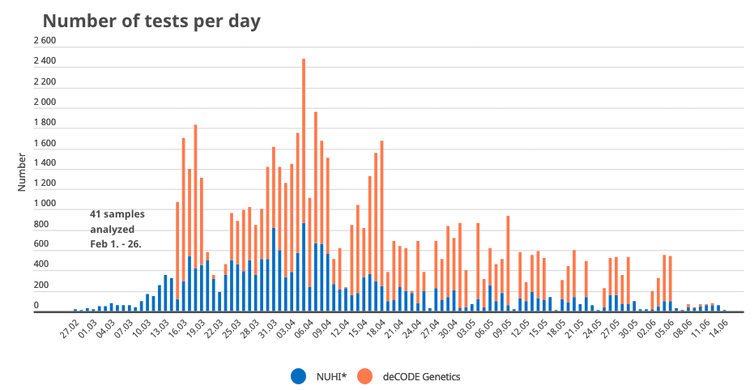

A public-private partnership between the National University Hospital of Iceland and deCODE Genetics enabled Iceland to carry out aggressive testing from February.

Government of Iceland

Similar to Taiwan, cooperation and coordination between Iceland’s government ministries and agencies have played a key role in quarantine and contact tracing.

The Directorate of Health worked with the Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management to create a team of 60 contact tracers in February, drawn from police investigators and healthcare workers. In this collaboration, the police contributed their expertise in traditional detective methods and enforced quarantine rules.

These two departments also partnered with a group of companies to create the Rakning C-19 tracing app in consultation with Iceland’s Data Protection Authority.

Read more:

Contact tracing is working around the world – here’s what the UK needs to do to succeed too

Public trust

The governments of both Taiwan and Iceland have secured high levels of public trust for their responses to coronavirus. In Taiwan, YouGov polls in May showed that public trust in the government and healthcare professionals on COVID-19 was very high – at over 80%. A combination of transparency and effectiveness may explain polling in April which suggested that 84% of Icelanders were willing to sacrifice some human rights if it helps to prevent the spread of the virus.

The example of these two countries shows how trust can be promoted by speedy government action to activate a crisis management and command centre which is headed by medical experts rather than politicians. Its purpose should be to coordinate cooperation between government and business and to communicate transparently with the public. This fits with a general lesson from cooperative strategies: openness between all parties is crucial and is a foundation for collaborative trust.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.