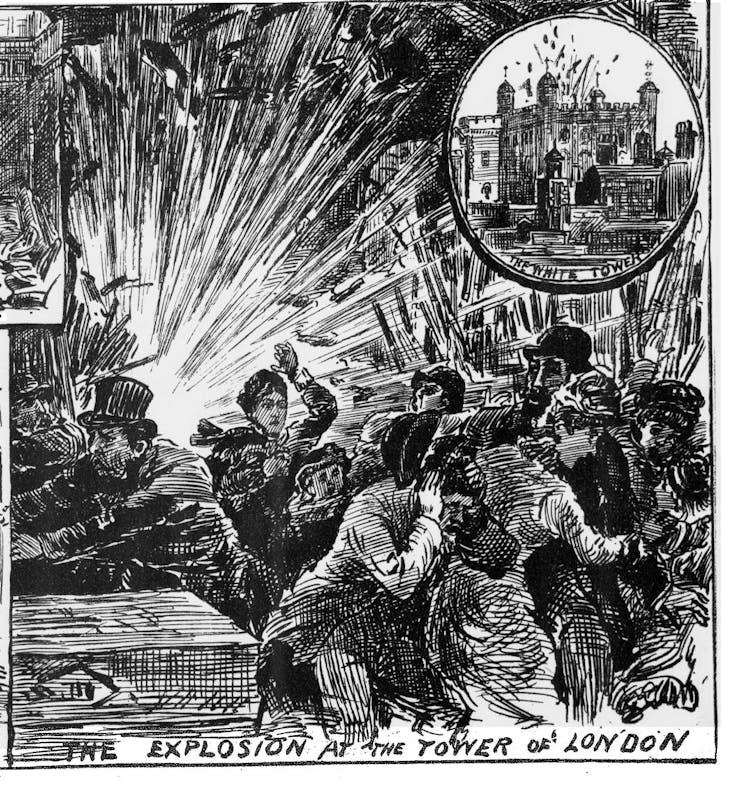

On the last day of February 1884, the then home secretary Sir William Harcourt rose in the UK parliament to answer a question about a series of bomb attacks on two of London’s major railway stations. He read out details of an initial investigation of two bombs, one which had detonated at Victoria Station and another which had been discovered, unexploded, at Charing Cross.

The bombs, which had been deposited in the stations’ left luggage offices, were of a similar design, and resembled the remains of bombs that had detonated, Harcourt said, in Glasgow, Liverpool and elsewhere in London. The unexploded device, discovered by a vigilant ticket clerk at Charing Cross, and the remains of the bomb that had detonated at Victoria were rushed to the Woolwich Arsenal.

According to Harcourt, the Charing Cross device comprised a “shabby black American-leather portmanteau, two feet by twelve inches”. But what it contained was of particular interest. As reported in The Telegraph, it was an “infernal machine” comprised of a clock, a pistol trigger mechanism, moving cogs and bars of a soft, chemical-smelling material.

An expert was called: Colonel Vivian Dering Majendie, a man whom, The Times reported, was renowned for being “most painstaking in his investigations” into explosive devices and the people who built them.

Majendie, according to the news report, had only to pick up and make a cursory examination of the chemical bars, in order conclude that they were – as all suspected – slabs of dynamite. He next turned his attention to the clock to which the extracted bars were attached, noting that its manufacturer’s stamp indicated an American origin. Finally, he examined the trigger mechanism, quickly determining that it had misfired, which was why the bomb had been a dud.

Dangerous as the examination had been, the act of coming face-to-face with devices designed to kill and capable of doing so at any moment was just another day for Her Majesty’s Inspector of Explosives. This was a title that had been bestowed on Majendie in 1871, reflecting both the esteem in which Majendie was held and the societal fears of terrorism that were gripping Britain in that era.

Forensics expert

Born in 1836, Majendie had served as an artillery officer in the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the Indian Rebellion (1857), before becoming an instructor at Woolwich Arsenal in the 1860s. In this capacity, he developed a reputation for expertise in the composition and assembly of explosive devices.

This led, in 1875, to him being appointed to advise the government on the wording of the first Explosives Act. The Act regulated the sale and production of gunpowder and dynamite – a substance invented in the 1860s for the purposes of mining. It had also quickly become the favoured weapon of Fenians (Irish republicans), anarchists, nihilists and other terrorists.

Majendie was also adept in the burgeoning discipline of forensics – he is regarded as the founder of today’s Forensics Explosives Lab (FEL) which – among other tasks – was at the forefront of the investigations into the Manchester bombing of 2017.

Nearly 140 years earlier, the man who laid the foundations for the FEL was tackling a different terrorist threat, namely the so-called “Fenian dynamite campaign” of 1881-1885, which involved bombs being placed in public and police buildings, tube stations and barracks, as well as onboard ships in London, Glasgow, Manchester and Liverpool.

TheIrishstory.com

Majendie served as both explosives analyst and detective in this original “war on terror”. His investigations into the bomb plots of February 1884 revealed that not only were the clock parts and explosives used similar in both the bomb that went off and the unexploded device, but that they were of American make. This led Majendie to the further conclusion that the origin of the attacks could be found on the other side of the Atlantic.

Security consultant

Beyond unravelling the transatlantic plots of those he called “dynamite rascals”, Majendie also advised the government on all manner of security issues, from how to remodel the Tower of London so as to protect it from insurgencies, to measures for securing the proposed Channel tunnel in the event of a continental invasion. In this sense, Majendie was more than just a bomb disposal expert – even if he was the first person in history to be recognised as such. He was also what might today be loosely termed a “security consultant”.

Despite these forays into planning the bricks and mortar of national security, Majendie’s stock in trade remained forensic explosive investigation. As such, in 1894, he crowned his career by investigating the French anarchist Martial Bourdin’s attempt to detonate a bomb at Greenwich Observatory.

Wikimedia Commons

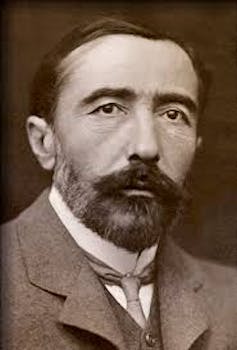

The sensation this created in the UK national press would later lead the novelist Joseph Conrad to pen his infamous 1907 tale of anarchist terrorism, The Secret Agent.

As always, Majendie provided a sober reality to the sensationalism that surrounded the bombing. Having examined Bourdin’s wounds and his “infernal machine”, Majendie concluded that the explosion had not been caused by the bomber tripping over his own feet (the buffoonish cause of the explosion provided by Conrad) and instead had simply mishandled the chemical components of the weapon.

Majendie’s investigation of the Greenwich bombing was one of the last triumphs of his storied career – he died of a heart attack in 1898. He was both an empirical investigator with a passion for science and, through his security consultancy, a participant in the panics over anarchist terrorism and foreign invasion that ran rampant in Britain at the end of the 19th century. Majendie embodied the contradictions of an age in which progress and rationality competed with societal fears in the midst of the first “war on terror” – a man both for and of his time.

![]()

James Crossland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.