Life outside the womb is tough – not least because of the many bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens that can harm a baby. Not only does a baby’s immune system need to be able to recognise and eliminate pathogens, it also needs to be able to distinguish harmless substances and helpful bacteria important for health – such as those in our gut microbiome, which help break down foods and protect us from pathogens.

Breastfeeding is known to be important for a baby’s immune development, and is also linked to numerous long-term health benefits, such as lower rates of obesity, asthma and autoimmune disorders compared to those who were formula fed. But until recently, researchers haven’t quite known why the immune systems of breastfed babies are better equipped compared to formula-fed infants.

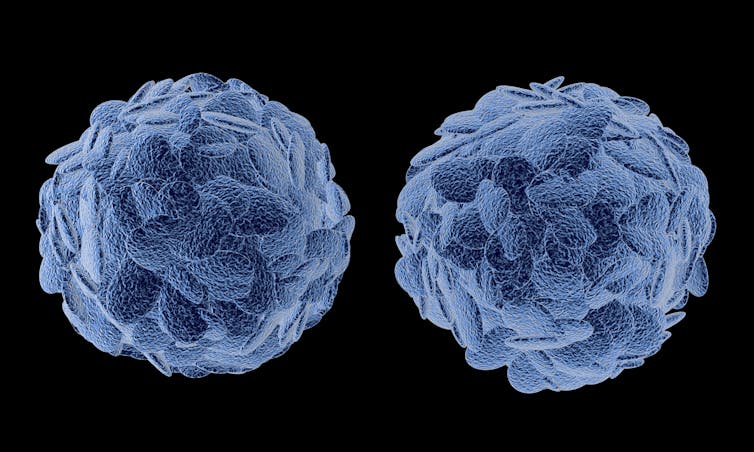

Our latest study may have the answer. We found that breastfeeding is important for helping babies to develop important immune cells in their first weeks of life. These immune cells, known as regulatory T cells, provide balance in the immune system by controlling its response to pathogens, and preventing autoimmune responses (where the immune system mistakenly attacks your body).

We studied blood and stool samples from a cohort of 38 healthy mother and baby pairs. All babies in the study were born by elective Caesarean section and samples were taken at birth and at three weeks of life.

We found that the population of regulatory T cells was nearly twice as abundant in breastfed babies at three weeks of age compared to babies who were formula-fed. This shows that these babies’ immune systems are better equipped to know which pathogens they should attack and which pathogens are harmless to the body. We demonstrated that this change is likely to be driven by interaction with the mother’s cells during breastfeeding.

ratlos/ Shutterstock

During pregnancy, the immune systems of the mother and baby are known to interact via cells moving through the placenta. Our results show that their immune systems continue interacting after birth via breastfeeding. We uncovered this by isolating immune cells from both the mother and baby, and growing them together in the lab.

The baby’s cells were less likely to see the mother’s cells as foreign if the baby was breastfed compared to formula-fed – an effect mediated by regulatory T cells. This means that the baby’s immune system “tolerates” these maternal cells from breastmilk and does not launch an immunological reaction, like it would do with any other foreign cell.

The early development of regulatory T cells is likely to be a key element in effective immune function in later life. This response is essential in preventing allergies, where the immune system mounts an undesirable response against harmless substances, and decreasing the risk of autoimmune disorders, where the immune system reacts against the body’s own cells.

Regulatory T cells are also of great importance in building an effective gut microbiome, which evolves gradually after birth. If the immune system eliminated, rather than tolerated, these gut microbes in early life, several of their beneficial health effects would be hindered. For example, this could lead to digestive problems, or could increase the risk of intestinal infections.

We also examined the composition of the gut microbiome in stool samples collected from babies at three weeks of age to understand how it is linked with immune development. We found subtle but important differences between breastfed and formula-fed babies. Two distinct bacterial strains, Veillonella and Gemella, were more abundant in samples of breastfed babies. These strains are known to produce short-chain fatty acids which are essential for the development and normal function of regulatory T cells. Greater presence of these strains in the gut may contribute to regulatory T cells being more abundant in blood samples of breastfed babies.

Although the number of participants in our study may appear small, we worked with a unique cohort of babies, creating the largest study of its kind to date. But our study also had some other shortcomings. For instance, we only followed up participants up to three weeks of life. It will be interesting to see in future studies how long the observed changes are present for in the immune system, and whether the number of regulatory T cells equalises in later life between breastfed and formula-fed babies.

And while we intentionally studied babies born by Caesarean section to observe a group exposed to as similar birthing conditions as possible, it will also be interesting for future studies to see whether our observations are also true for babies born by normal delivery.

While breastfeeding is recommended for infant nutrition by the World Health Organization, there are of course many reasons why a mother may need to formula-feed her baby. And in most developed countries, this alternative is safe for babies, and the composition of many infant formulas is frequently changed to be as close to breastmilk as possible. Although it’s unlikely that breastmilk can ever be fully mimicked, research like ours may help to guide the tailoring of formula milk to offer better health advantages to all babies.

![]()

Gergely Toldi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.