Alex Salmond has died having failed to achieve just two of his great ambitions – make Scotland an independent country, and judge the annual Tartan B*****s contest for the worst Scottish political story of the year, held at the strictly private Christmas dinner for Holyrood hacks.

The first he almost achieved in 2014, the second he begged each year to be allowed admittance to, when he hosted festive curry nights for journalists at the first minister’s residence Bute House. It suited his tastes for revenge and humiliating others.

My first memory of meeting Salmond involved walking down Union Street in Aberdeen in 2007 and watching as people ran out of shops to come and shake his hand and talk to him.

The only other two British politicians I have witnessed receiving such adulation were Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, who in many ways shared the populist ingredients to change the UK story. Salmond brought the SNP to power and almost delivered independence, Farage delivered Brexit and destroyed the Tories.

Salmond’s untimely death at 69 in North Macedonia brings back some very mixed recollections of a man extraordinarily gifted politically, but who also possessed deep flaws.

Close contact with him ranged from him being the most charming person you could ever meet to a monstrous bully.

For a brief time I was in the circle of trusted journalists when I worked in Holyrood for his local paper the Aberdeen Evening Express between late 2006 and early 2008.

He would almost always pick up the phone, and when we met in the Scottish Parliament he would be charm itself, often putting his arm round me, asking how I was.

Salmond could frame the moment. I remember several conversations on the night of the election victory in 2007, when he would tell me: “I don’t know if I have won but Labour has certainly lost.”

But about a fortnight before I changed newspaper one of his advisers told me: “Pity you are leaving forThe Scotsman. You know none of us are going to speak to you when you do that.”

It was not a joke.

A week later I did my final story for the Evening Express. It was the exclusive interview with Salmond after he had been cleared in an inquiry into whether he had interfered to help Donald Trump (who he was at one time very close to and then became bitter enemies with) get planning permission for his golf course in Aberdeenshire.

It turned out also to be a parting gift. A week later, with me arriving at The Scotsman, Salmond literally turned his back when he saw me. Salmond was Trumpian long before Donald Trump – no wonder the two originally got on so well. He, more than any other politician, taught me political journalism is a contact sport.

But that was how he did things. Journalists in Holyrood were divided into nationalists and unionists. It was how Salmond as first minister would divide Scotland.

The Independent’s Whitehall editor Kate Devlin was also reporting on Scottish politics with the Daily Telegraph and Glasgow Herald and recalls how he was “cagey” with female hacks and seemed to prefer dealing with men.

But she pointed out how he liked to claim that the careers of Scottish journalists were thanks to him – after he boosted interest in Scottish independence.

“He was once entirely unembarrassed when the journalist in person turned out not to be Scottish but from Ulster,” she said. “‘Ah, but Ulster Scots?,’ he asked me.”.

In 2008 the Glasgow East by-election became a touch point moment in Salmond’s march to create an SNP hegemony in Scotland.

I wrote a piece mocking Salmond’s well known love for gambling and suggesting that this was a bet he was about to lose after seeing canvas returns for Labour. The SNP then won by 365 votes.

At the victory press conference, I saw Salmond looking around the forest of hands for the final question until he found me.

It did not matter what I asked – he was never going to answer. Instead on live television he read out my piece and poked fun at me to the laughter of all the SNP supporters in the room. A “proper monstering”, as a colleague noted.

It underlined everything about Salmond. He revelled in proving people wrong, could destroy you in a few words, and was incredibly thin-skinned.

Years later, after he had got back to Westminster in 2015, I had written a piece based on a briefing suggesting he might lose to the Lib Dems, which of course he then won. I ran into him in a bar in parliament.

Salmond wandered over carrying two glasses of pink champagne – which Kate points out was his preferred tipple there – and handed me one with a twinkle in his eye.

“According to you I’m not supposed to be here,” he laughed. “Cheers!”

As Kate noted, despite his belief in independence, he loved the House of Commons and being in Westminster. As well as the chamber, he enjoyed the social side of Parliament, spending nights on the Commons terrace.

The divisions Salmond deliberately created made for a frightening Scotland to live in. Covering the patch, I had the windows of my home smashed seven times, death threats, and the rest, from SNP supporters before I was transferred to Westminster. Twitter trolling first became a thing with SNP supporters under his leadership.

I am glad I did not live in Scotland during the referendum period when people were putting up Yes posters at their home for protection and then voting No.

During that period between 2012 and 2014, Salmond and the SNP stopped at nothing. He tried to get me sacked for reporting on a leak from the EU saying Scotland would not automatically be allowed in as members if they became independent.

Nothing underlined how he divided up journalists into two groups more than his ungracious defeat in the referendum. Only pro-independence journalists were invited for his press conference conceding defeat, although the rest of us gatecrashed.

The next day he deliberately kept out many publications and journalists who were seen as “unionist” as he announced his resignation as first minister.

As first minister, Salmond went after lesser Labour politicians with a ruthlessness that often verged on bullying. Wendy Alexander and Iain Gray were utterly destroyed and humiliated by him.

But being the complex man he was, you would see Salmond go after prey like “Looord” George Foulkes but then he would go for a drink with them at another time and talk about their shared love of Hearts football club.

However, the devotion in his inner circle had a dark side. One former aide who was going to the private sector, said to me: “He (Salmond) will always be my boss though… always.”

There was a cultishness about it. Beyond mere loyalty. The fact that person would later be involved in the sex crime allegations against Salmond did not surprise me. It did lead me to question what really happened. Did he abuse his immense personal power? Or was this, as he alleged, a Nicola Sturgeon-led plot against him?

It may be that both explanations were true. He was cleared in the criminal court but a subsequent Scottish government inquiry into the prosecution upheld five alleged victims’ complaints. What is beyond doubt is that the scandal destroyed Salmond as an SNP politician and led to the creation of the rival Alba, which never proved to be a vehicle which could rekindle his old flame.

Salmond felt there was a lack of gratitude to him from the SNP establishment. It was he who returned as leader in 2006 on the wave of anger about the Iraq War to save the SNP from irrelevance under John Swinney and lead them to victory and now 17 years of power. Swinney, Sturgeon, Humza Yousaf and many other glittering SNP careers are all thanks to him.

Yet the way they turned against him reflects that many considered him to be a monster. His questionable morality was never better highlighted than doing a regular show on Putin’s propaganda channel Russia Today.

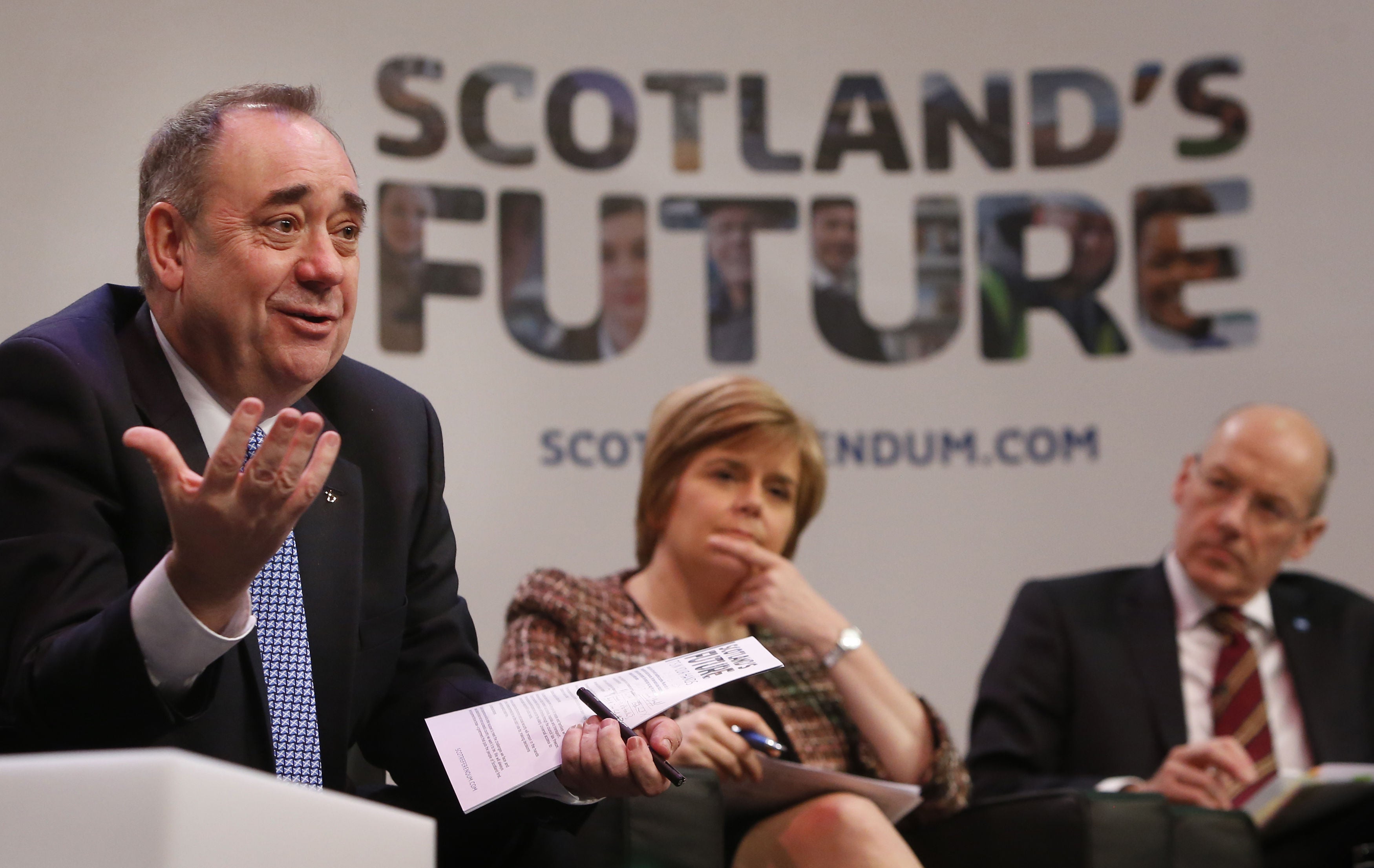

As a political journalist, you want to be reporting on the great moments of history as they happen and the most consequential figures. Writing the first page of history. Kate and I were lucky enough to be reporting from the frontline of Scottish politics through the extraordinary dominance of Salmond; from seizing power in Holyrood in 2007 to crushing Labour properly in 2011, the independence referendum in 2014, to his return to Westminster at the head of a massive cohort of 56 SNP MPs in 2015.

Love him or loathe him, it was always a privilege to be covering him. People speak of consequential politicians and Salmond was always, good or bad, a man of consequence.