A new test using easy-to-collect cells from the inside of the cheek can predict a person’s risk of death within the coming 12 months, scientists say.

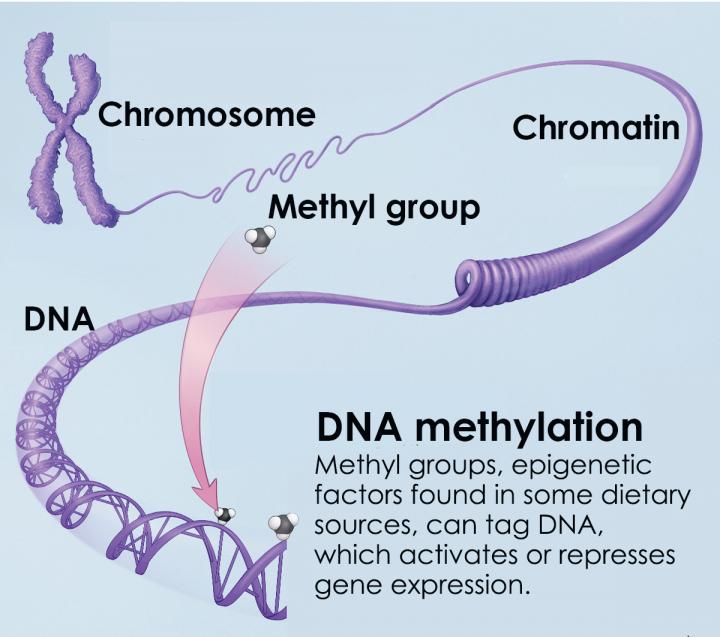

Previous studies have shown that behavioural and lifestyle factors like stress, poor sleep and nutrition, smoking, and alcohol consumption can speed up ageing, the effects of which tend to get imprinted on our genome as “epigenetic marks”.

These appear in the form of chemical modifications to DNA such as the addition of methyl molecules. Such changes make it possible to quantify the body’s ageing progression at the molecular level.

Previous efforts to test the extent of molecular ageing markers have relied on examining blood cells, the collection of which can be onerous.

A new study published in the journal Frontiers in Ageing describes a new method to determine the extent of biological ageing from epigenetic marks in cells collected from cheek swabs.

Researchers say the new test, called “CheekAge”, can establish potential links between specific genes in the body and processes driving human mortality.

The test was developed by correlating the fraction of methyl group modifications at around 200,000 sites in the human genome with an overall score for health and lifestyle.

It was then used to predict mortality from any cause in over 1,500 women and men born in 1921 and 1936.

The findings revealed that CheekAge is “significantly associated with mortality in a longitudinal dataset”. They also suggest that there are common signals of mortality across tissues in the body.

“This implies that a simple, non-invasive cheek swab can be a valuable alternative for studying and tracking the biology of ageing,” study author Maxim Shokhirev says.

Inside the genome, scientists looked at DNA methylation sites most strongly associated with death in greater detail. They found genes around or near some of these sites are potential candidates for impacting lifespan or the risk of age-related disease. The potential candidates include PDZRN4, a gene thought to play a possible role in suppressing tumour growth, and ALPK2, a gene implicated in cancer and heart health.

They also found genes previously implicated in the development of cancer, osteoporosis, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome seem to impact lifespan.

“Future studies are also needed to identify what other associations besides all-cause mortality can be captured with CheekAge,” Adiv Johnson, another of the study’s authors, said.

“For example, other possible associations might include the incidence of various age-related diseases or the duration of ‘healthspan’, the period of healthy life free of age-related chronic disease and disability.”