Being overweight increases the risk of many serious health conditions, including strokes, cancer, diabetes and hypertension. Less well known, perhaps, is the link between being overweight or obese and the health of our brain. Research has shown that a higher body mass index and mid-life obesity are both linked to increased risk of dementia. Some evidence also indicates that obesity and Alzheimer’s disease cause similar brain dysfunctions.

Our latest research has now shown that being overweight or obese negatively affects brain health, especially in the regions most vulnerable to the effects of Alzheimer’s disease. This could potentially exacerbate symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease should it develop.

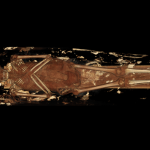

Our study looked at 57 people who were healthy and had no sign of Alzheimer’s, 68 patients who had mild cognitive impairment but could still function normally in everyday life, and 47 patients with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia. We took measurements of each participant’s body mass index and waist circumference to determine whether they were a normal weight, overweight or underweight. We then invited all participants to have an MRI scan to measure the structure of their brain (such as its volume and the number of connecting fibres), as well as its function, as measured by blood-flow levels.

Our findings showed that in overweight or obese people who had no or mild cognitive impairment, the more excess weight they carried, the greater their levels of brain cell loss and the lower their brain blood flow. We also found some damage to fibres that connect brain cells. All of these changes affect mental functions, including how well we remember things and our ability to do everyday tasks.

We also found that these changes occurred in the frontal, temporal and parietal brain regions. Not only do these regions play an important role in memory, planning and interpretation of the visual world, they’re also areas where Alzeimer’s causes the greatest amount of cell loss and decreased blood flow.

Robert Kneschke/ Shutterstock

Interestingly, in patients with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, the healthier their weight, the less they showed brain cell loss. This suggests that maintaining a healthy weight after being diagnosed with dementia may help patients preserve more brain cells for longer, slightly slowing progression of the disease.

Excess weight

Our findings show how complex the relationship between maintaining a healthy weight and brain health is. While our study doesn’t show obesity or excess weight to be a direct cause of Alzheimer’s disease, the findings do suggest that being overweight or obese throughout a person’s lifetime lowers the brain’s resilience to the damaging effects of the disease. This results in more severe symptoms and faster decline in those who develop Alzheimer’s.

Our study also highlights the importance of looking after our weight from an early age to avoid the negative effects of excess weight on the brain. This is especially important after middle age, where the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease increases considerably – and because damage to the brain is usually not reversible and accumulates over time.

Although the cause of Alzheimer’s disease is not known, we know that a number of factors can increase our risk of developing it – excess weight being one of them. Obesity puts a severe strain on the cardiovascular system and damages the brain vessels’ walls.

This in turn results in high levels of inflammation, toxicity to brain cells, and lower metabolism and blood flow in the brain. Our study adds to the large body of evidence that indicates the damaging effects of obesity on the vascular system worsen some of the mechanisms that cause Alzheimer’s disease.

There’s still no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, which is why it’s important to take as many precautions as possible from an early age to prevent the likelihood of developing it.

![]()

Annalena Venneri receives funding from EU, MRC, EPSRC, ARUK, Italian Ministry of Health, NIHR, Royal Society, Welcome, Leverhulme. She is affiliated with Sheffield Teaching Hospital NHS Trust, Brunel University London.

Matteo De Marco ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.