Smells, scents and stenches are a common feature in the messy world of sex. In animals, aromas such as pheromones are often used to attract and charm potential mates. But some male butterflies use sex smells for another purpose entirely: to deposit a stench on their coital partner so foul that other potential suitors will give her a wide berth.

This jealous behaviour from one of nature’s most beloved insects is not without precedent. A previous study found that some male butterflies effectively slap a “chastity belt” on their mates, plugging their sexual organs to hamper the attempts of other males to mate with the female.

And although a stink is perhaps a less permanent parting gift than a genital plug, it’s still motivated by the same key evolutionary incentive: male butterflies will be favoured by natural selection if it’s their sperm that is fertilised in a female – not that of their rivals.

Turning off other males with a smelly signal ensures the male butterfly’s paternity – giving other suitors cause to take wing and avoid the newly impregnated female. The smell might also benefit the female, who can safely store sperm from the first male while avoiding costly harassment from other males.

What’s particularly striking about the chemical that produces this post-coital stink – identified some years ago as a compound called beta-ocimene – is that it occurs in flowering plants as well as in butterflies.

For years, this has puzzled researchers. How is the very same chemical compound produced by plants and butterflies – two very distantly related species? Our recent study used genome mapping (which reveals the DNA sequence of an organism) to answer this question. In doing so, we identified a novel gene that produces beta-ocimene in butterflies, entirely distinct from those known in plants.

Several smells

While it’s unusual for insects to produce chemical compounds found in plants, it’s also important to highlight that different butterfly species have access to a vast arsenal of different smelly compounds.

Our study involved the South American butterfly genus known as heliconius, in which even closely related species deploy a different type of chemical bouquet on their female partner.

The existence of this wide range of smells suggests rapid evolution – a quick turnover of pongs, stinks and stenches in the heliconius genus. In the wild, these smells battle for dominance, with the stinkiest odour resulting in the fewest males “trying it on” with an already-mated female.

Sequencing a stench

We know that the smelly beta-ocimene compound is not found in all heliconius butterflies. For instance, it’s present in heliconius melpomene butterflies, but not the closely related heliconius cydno butterfly. We realised that mating these butterflies, and examining which smell their offspring used, would help us understand how these smells evolve.

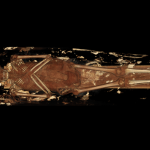

The first step of this project began at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, in a small town on the Panama Canal called Gamboa. We mated the two species of butterfly to create hybrids, analysed the smelly chemicals produced by these hybrids, and sequenced their genomes to create a complete map of their DNA.

This approach, known as “quantitative trait locus mapping”, allowed us to identify a section of the butterfly’s genome associated with pheromone production – the gene at the source of the smells.

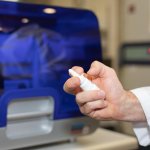

We then transferred this gene into simple bacteria, which happen to use a very similar genetic code to insects. The bacteria with the smelly gene were then tested in a controlled chemical environment, to see if they would produce the beta-ocimene we so often see in flowering plants.

In performing this experiment, we identified a novel gene, HMEL ocimene synthase, which produces beta-ocimene in heliconius melpomene butterflies in a completely different way to how it’s produced in plants. This gene is in no way related to the plant genes we already know to produce beta-ocimene.

The independent evolution of the same trait in plants and insects – in this case, pheromone production – helps us understand evolution a little better.

And, while beta-ocimene is produced by plants to tempt insects towards their pollen-rich flowers, it’s deployed by male butterflies to ward off rivals in the rancid game of butterfly love – showing that, when it comes to smells, context really is everything.

Chris Jiggins receives funding from European Research Council, BBSRC and NERC.

Kathleen Darragh received funding from NERC (Natural Environment Research Council) and STRI (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute).