Dinosaur fossils have always amazed with their horns and spikes, enchanting us with elongated necks and foot-long teeth. But less attention has been paid to the dinosaur derriere – for reasons of taste, maybe, but also because it’s difficult to find a well-preserved bottom in the fossil record of our Mesozoic friends.

But a chance encounter at a German museum has helped us understand the story behind one dinosaur’s behind, revealing that the creature’s back opening might have been “flashed” for communicative purposes – much like baboons use their bottoms for communication today.

The dinosaur rear is different than the mammalian one we’re familiar with. Where mammals evolved separate openings for reproduction and the expulsion of faeces, dinosaurs and their relatives possess one single rear orifice called the “cloaca”. This all-purpose opening was used for defecation, urination, mating, and the laying of eggs.

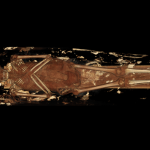

While we’ve long known that extinct dinosaurs would have had a cloaca, no fossil had actually preserved those parts well enough to be closely studied. But recently, a number of amazing discoveries of dinosaur fossils across northeastern China have revealed birds and non-avian dinosaurs with immaculately preserved feathers and clear markings on scaly skin.

A new dimension

These Chinese fossils are so well preserved that even melanin pigment – which determines the colour of skin, hair, and scales – is visible. This has enabled palaeontologists to reconstruct dinosaurs with their original colour patterns, transforming monochrome 2D fossils into colourful 3D representations.

Read more:

Six amazing dinosaur discoveries that changed the world

With the help of palaeoartist Bob Nicholls, we previously reconstructed the original colour patterns from a small herbivorous dinosaur called psittacosaurus, which lived over 100 million years ago. It is a labrador-sized herbivorous dinosaur, closely related to the much larger ceratopsians group of dinosaurs – of which the triceratops is the best-known example.

We reconstructed the original colour patterns of the psittacosaurus from a beautiful fossil specimen held at the Senckenberg Museum of Natural History in Frankfurt. By projecting this reconstruction onto a lifesize 3D model, we revealed that it had counter-shaded camouflage, helping it conceal itself in wooded areas.

Rock bottom

But this particular dinosaur still had some secrets to reveal. After completing the study on the psittacosaurus’ colour patterns, we made a casual return to the Senckenberg Museum – to film a video abstract that showed how we reconstructed the dinosaur’s colours.

As we filmed, we noticed that the cloacal opening (or vent) was extremely well preserved, captured in this video. We believed we could reconstruct this lesser-studied part of a dinosaur’s anatomy, too.

And so we set out to reconstruct this psittacosaurs’ cloacal region – rebuilding a backside from over 130 million years ago.

Our final reconstruction revealed a pair of lips on either side of the opening, which flared outward in the direction of the tail tip. Between the lips, a section of the tail formed a swollen lobe. Together, these three parts formed the entry point for mating and the exit point for eggs, faeces, and urine. If it was a male, the opening would probably have hidden a penis, too.

We noted in particular that the scales on the cloacal lips were very dark, due to melanin pigment inside them. Because the underside of the dinosaur was light in colour, the dark cloaca will have stood out dramatically when the psittacosaurs was alive. In an effort to explain this, we turned to nature’s different backsides for answers.

Comparing behinds

Dinosaurs and avian species coexisted. We know birds have evolved visual signalling for species recognition and sexual selection – the obvious example being the male peacock’s dazzling feathers.

Some living birds actually use cloacal visual signalling, although it is rare given that birds’ vents are usually covered by their feathers. One present-day example, the Alpine Accentor, sees the female flashing her colourful cloaca during courtship.

Simon Vasut/Shutterstock

We now know dinosaurs had advanced forms of visual signalling too, like iridescent feathers. And so-called ‘naked’ dinosaurs – covered in scales rather than feathers – could well have used cloacal signalling in the absence of these feathers.

Our well-preserved dinosaur fossil may therefore have provided a rare glimpse into a widespread social behaviour among dinosaurs – though it’s difficult to say whether this behaviour was used for mating displays or other forms of communication.

We can’t really say for sure until we have more well-preserved cloacal vent fossils to compare our findings against – but our evidence certainly suggests that hundreds of millions of years ago, dinosaurs flashed their behinds as a form of communication.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.