Coronavirus is causing a strain on health services around the world. Just last week, over 80% of critical care beds in England were full, with warnings of hospitals hitting their limits in the coming days.

Because of the fast moving and uncertain nature of the pandemic, it is difficult to predict with any certainty how many beds will be required, even over a relatively short timescale. One option would be to reduce admissions of non-COVID patients, but that is normally a last resort.

Faced with an unexpected rise in admissions, senior managers responsible for hospital bed planning have relatively few levers at their disposal. Unfortunately, unforeseen events such as the rapid spread of novel variants make it easy to get such decisions wrong.

This is where academic modelling teams like ours can provide practical guidance and advice at both national and local hospital levels.

Working in an emergency

Our team works with NHS Lanarkshire (NHSL), which is the third largest integrated Health Board in NHS Scotland, serving a population of about 660,000 people. NHSL manages three large general hospitals, together comprising more than 1,400 inpatient beds, plus several small community hospitals.

We have been providing NHSL with detailed local COVID-19 modelling support since early March 2020, to complement the national advice and guidance.

March 2020

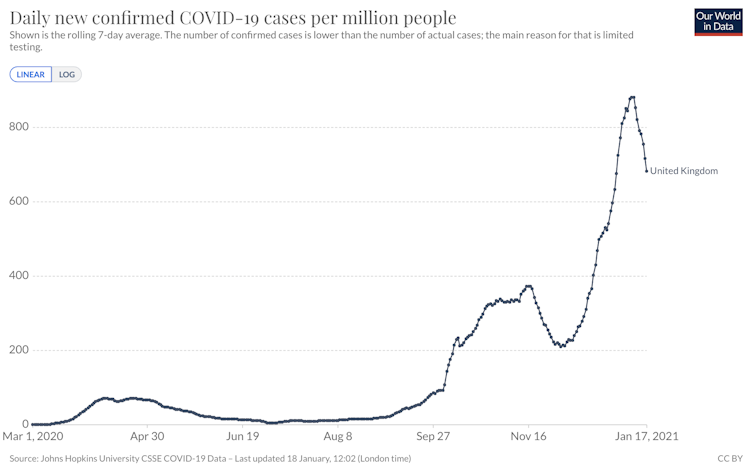

In the middle of March 2020, new confirmed COVID-19 cases in the UK were rising very rapidly. London seemed to be the worst hit but the situation appeared to becoming critical in Scotland, too.

Health Boards, including NHS Lanarkshire, were getting strong advice from the Scottish Government to substantially reduce hospital admissions of non-COVID patients. Operating theatres were cleared of their normal equipment and filled with COVID-19 beds. Patients who were in hospital for other reasons, many of them elderly, were discharged as soon as practicable or transferred into care homes.

However, by the end of March 2020, we were already able to predict the peak of COVID-19 cases would be reached in the first two weeks of April. In consequence, plans for further reductions in non-COVID healthcare could be shelved at an earlier stage than would have been possible otherwise, and hospital managers could contemplate the future with greater confidence.

How the models work

Computer models estimating the requirement for hospital beds, whether in intensive care units (ICU), high dependency units (HDUs) or general wards, need to take into account a few key factors.

These include the number of new infections, the estimated proportion of infected people requiring hospital admission, the probability of the length of stay and the number of beds already occupied, whether by COVID-19 patients or people admitted for unrelated conditions.

Read more:

Mutating coronavirus: reaching herd immunity just got harder, but there is still hope

As the full force of the COVID-19 pandemic started to become nationally apparent, a key question was how many intensive care beds would be needed locally for the impending surge in COVID-19 patients.

Our modelling team, which initially also included Dr Nicola Irvine a consultant in acute medicine, collaborated closely with the public health department. Along with Chandrava Sinha, we built a model showing the impact of expected new COVID-19 cases, with a detailed age profile, on the use of ICU, HDU and general ward beds over a six- to eight-week planning horizon.

The resulting model provided NHSL executives with a tool to predict critical needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. But an important strength was our ability to incorporate detailed local data – for example on age profiles, length of stay distributions, local clusters of cases – into the national picture.

OurWorldInData, CC BY

The situation today

Essentially, the same scenario we faced in March 2020 is playing out now. COVID-19 cases rose very rapidly across the Christmas and New Year period, as the novel coronavirus variant was taking hold.

As before, urgent questions have arisen about how much non-COVID healthcare activity should be curtailed. Again, we are inserting the latest case data and age profiles into our computer model to support senior managers in making these difficult decisions.

It is already becoming clear the current national lockdown measures are having a significant dampening effect on the growth in new cases in Lanarkshire and elsewhere. This new downward trend in cases is reflected in our latest forecasts, presented last week, for bed occupancy over the next six weeks. They show a substantial reduction compared with forecasts we produced only a fortnight ago.

Computer modelling can offer a vital tool during situations when planning resources in scenarios hospitals have never encountered before. To be effective, modelling support must be timely and realistic, while properly reflecting the high degree of uncertainty involved.

![]()

Robert Van Der Meer receives funding from Scottish Government, NHS Lanarkshire, Pancreatic Cancer UK, Cancer Research UK.

Gillian Hopkins Anderson receives funding from Scottish Government.