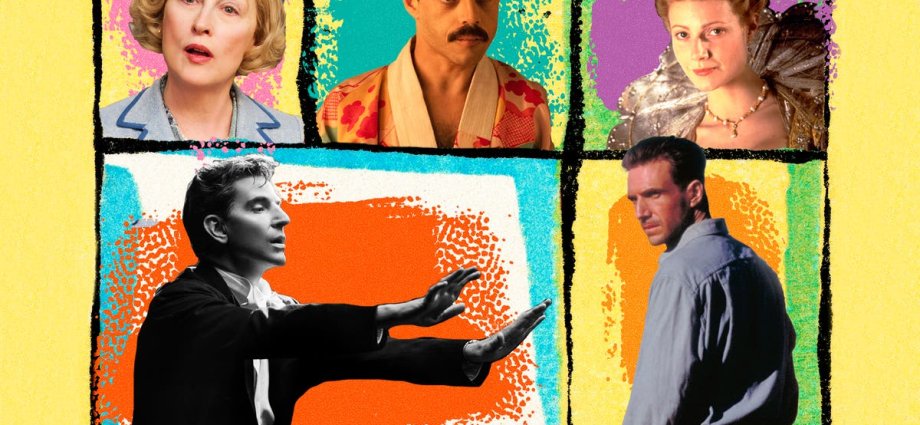

Take one real-life story, ideally about an important person from the past. Hopefully their tale is set during a war, or a time of general strife, so there are plenty of obstacles that can be overcome to the sound of swelling orchestral music. Cast an actor who’s much better looking than the real important person, so that they can spend hours in the make-up chair during the film shoot, giving them some anecdotes for the chat show circuit. Present them with a few set-piece speeches that will look good when played out-of-context during an awards ceremony. Ask Meryl Streep if she’s around for a glorified cameo that has “Best Supporting Actress” written all over it, and voila! You perhaps have the perfect Oscar bait.

If you pay attention to the film calendar, you’ll have noticed that every year without fail, winter time sees cinemas filled with this sort of film: worthy, weighty stories, ones that, we’re told, “speak to the current moment” somehow, even if they’re set in the 18th century and are filled with crinolines. Movies, in other words, that are doing everything they can to earn themselves an Academy Award. The term Oscar bait has come to sum up this glut of well-made, often earnest productions, which prove that prestige movie-making can be as formulaic as genre blockbusters. In its most dispiriting form, awards bait is Rami Malek wearing fake teeth and lip-syncing to Queen’s greatest hits in Bohemian Rhapsody, or whatever Crash was.

Perhaps this year’s most blatantly Oscar-baiting contender is Maestro, the latest film from Bradley Cooper. Learning to sing and play guitar for his 2018 remake of A Star is Born – as well as lowering his voice about an octave and undergoing a punishing self-tanning schedule – clearly wasn’t enough: the film’s eight Oscar nominations resulted in just one win (for Best Original Song). So for his second film, Cooper has doubled down. In Maestro, he plays – while wearing a dubious prosthetic nose – the legendary composer Leonard Bernstein, having spent six years learning how to conduct an orchestra (Oscar voters apparently love to see one of their own mastering a niche new hobby, like when Margot Robbie got really good at ice-skating for I, Tonya).

Again, Cooper’s efforts have resulted in a swathe of nominations (seven, this time). But will those nods amount to anything on Oscar night? The smart money is on Maestro getting trounced by Oppenheimer. On paper, Christopher Nolan’s movie is, yes, another film chronicling the life and times of a famous American, requiring a physical transformation from its lead, and sometimes shot in black and white. But somehow, despite all that, Oppenheimer hasn’t been cast as quite so, well, baity. Perhaps it’s a goodwill hangover from last summer’s “Barbenheimer”phenomenon, perhaps it has connected better with viewers, or perhaps it just doesn’t seem so keen on success. Herein lies the strange conundrum of Oscar bait. Sometimes, if you try too hard, you ruin your chances. “Cooper has accidentally violated one of the cardinal rules of campaigning,” Vulture claimed earlier this year. “Show you want it, but don’t be desperate.”

Sticking close to the old Oscar bait template, then, isn’t a sure-fire route to glory: how an awards campaign is managed is just as important (and, erm, so is the actual quality of the film: believe it or not, but there was an innocent time when Cats was considered a potential Oscar contender). And sometimes this backfires well before the Academy has finalised its shortlists: it’s not uncommon to hear a film touted as a major awards contender around autumn festival season, only for its hopes to be dead on arrival come mid-January. Imagine the unique humiliation of spending three months telling chat show hosts about how you’d, say, learned to yodel or whittle spoons as part of your Method process, then hearing crickets on nomination morning.

Spoils of war: the surprise triumph of ‘The Deer Hunter’ is seen as a template for Oscar glory

(Shutterstock)

The phrase “Oscar bait” dates all the way back to 1948, when it appeared in US magazine The New Republic’s damning review of Fort Apache, a Western from director John Ford. At this point, Ford was indeed a three-time Best Director winner (and would receive a fourth trophy a few years later), which raises the chicken-egg question of whether his style was actually pandering to Academy voters, or whether those Academy voters just enjoyed the sort of films he made (at this point, the Academy Awards had only been running for about two decades, so ideas about what did and did not constitute an Oscar movie weren’t quite so codified).

Glance at the winners’ lists from the next few decades and you can see the rubric for Oscar success gradually emerging. Long, weighty historical epics dominate the Best Picture category (and around the middle of the century, musicals were awards magnets too); in the acting fields, characters from literary adaptations and real-life stories abound. But what we now think of as Oscar bait really exploded when the gap between box office success and industry prestige started to widen. Towards the start of the Seventies, it was common to see some of the year’s highest grossing films recognised in the Best Picture category. Then came the dawn of the “summer blockbuster”. Directors like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas’ earliest crowd-pleasers Jaws and Star Wars were both Best Picture contenders over two consecutive years, but after that, box office success and Oscar glory started to diverge. At the same time, filmmakers (or more accurately, film marketers) awoke to the fact that awards prestige could help shift tickets for a smaller, less mainstream movie that might otherwise be a hard sell.

Take 1978’s The Deer Hunter, which had an awards campaign now regarded as the blueprint for all Oscar campaigns to come. After a woeful test screening, the studios were ready to trash this bleak, three-hour epic about traumatised Vietnam War veterans. Then a saviour emerged in the form of Broadway and film producer Allan Carr, fresh from working on promotion for a very different film, Grease. He arranged enough screenings to make it Oscar eligible, then The Deer Hunter practically disappeared (apart from a few showings on Z Channel, a cable network for film devotees based in Los Angeles – a channel likely to be frequented by industry types). When The Deer Hunter received nine Oscar nominations, it returned to cinemas around the country, with posters shouting about its Academy Award prestige. It all paid off: the film grossed around $50m and finished Oscar night with five trophies (including Best Picture). Producers started to sit up and see that awards success could equal a major box office boost.

In the Nineties, Harvey Weinstein took a bullish, often bullying approach to campaigning – and shaped what we still consider “awards-worthy” in the process. Miramax, the film company Weinstein founded with his brother Bob, initially balanced edgier fare from then-rising directors like Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh with well-made, slightly sentimental indie dramas (which often happened to be period pieces, literary adaptations, or biopics: think The English Patient or My Left Foot). Weinstein got these films in front of Academy voters thanks to a barrage of aggressive tactics: phoning up retired actors who still held voting rights, setting up screenings in the Motion Picture Retirement Home, and reportedly even orchestrating smear campaigns to try and wipe out the competition. His efforts were brutally effective: his most notorious success remains Shakespeare in Love in 1999, with the film winning five trophies and beating frontrunner Saving Private Ryan to the Best Picture title.

Access unlimited streaming of movies and TV shows with Amazon Prime Video

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Access unlimited streaming of movies and TV shows with Amazon Prime Video

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

The movies that Weinstein elevated so successfully solidified the formula for Oscar bait. They also showed that a narrative about the film was just as important as the film’s actual story. Promoting a biopic about a historical figure who was under-appreciated or even mistreated in their own time? Why not claim that a vote for the film is a way of finally celebrating their legacy? Take the campaign for The Imitation Game, another Weinstein film, this time about Alan Turing’s work at Bletchley Park. In the run-up to awards season, “For Your Consideration” billboards appeared around Los Angeles, bearing the emotionally manipulative message “Honour the man. Honour the film”.

Real-life hero: biopics, like ‘The Imitation Game’, have won the Academy’s favour regularly over the years

(Weinstein Company)

Of course, the idea of Oscar bait is a contested one. The author and journalist Mark Harris has described it as “a terrible term that takes our sideline fixation [the Oscar race] and tries to recast it as a defining motive for artists”. In other words, it’s wrong (and deeply cynical) to believe that filmmakers set out with the sole purpose of making a film that picks up trophies. Making a film is such a long, draining and costly endeavour that surely the people behind it must believe in its message. Sometimes it feels like talking about Oscar bait is just another way to show off superior, more discerning taste: other people might be impressed by the gorgeous period costuming, sweeping score and third act monologue perfect for an awards show montage, but you’re certainly not.

Perhaps one day, it will become an outdated term. After the #OscarsSoWhite backlash in 2016, a response to the Academy failing to nominate a single person of colour in all four acting categories that year, the organisation has made a concerted effort to expand and diversify its membership. It’s more difficult to make generalisations about voters’ tastes, which has made certain races a little harder to predict. If you’d suggested a few years back that a film in which the protagonist’s fingers turn into hot dogs would one day win Best Picture, you’d probably have received worried looks among awards prognosticators. And yet last year Everything Everywhere All at Once practically pulled off a clean sweep, sausage hands and all.

Whether or not that film’s success marks a “new normal” remains to be seen. But wouldn’t it be nice if, going forward, the Academy made room for tear-jerking true stories and wacky, genre-defying action-comedy-dramas?