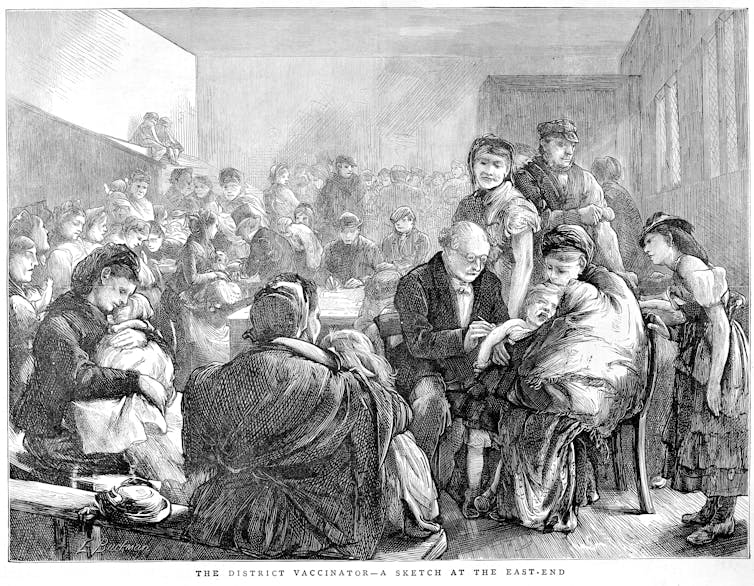

E.E. Hillemacher/Wellcome Collection

As the 1906 UK general election results rolled in, it became clear that the Conservative party, after 11 years in power, had suffered one of the most disastrous defeats in its history. Of 402 Conservative MPs, 251 lost their seats, including their candidate for prime minister, defeated on a 22.5% swing against him in the constituency he had held for two decades.

Rising food prices, unpopular taxes and an opposition that promised to spend heavily on an expanded welfare state all contributed to the Tory downfall that year. But something else had tipped the opposition Liberal landslide over the edge – compulsory vaccination.

Anti-vaccination campaigner Arnold Lupton had taken Sleaford in Lincolnshire for the Liberals on a 12% swing and immediately started his parliamentary campaign to abolish compulsory vaccination against smallpox, a public health policy that had been in place in England and Wales since 1853 (with Scottish and Irish legislation following suit in later years).

Hardly a single Conservative MP was an anti-vaccinator, but 174 of the 397 Liberal MPs in the new parliament signed Lupton’s petition.

Their attempt at changing the law was unsuccessful, but this flexing of parliamentary muscle by the anti-vaccinators persuaded the new Liberal government that the most expedient option was to reach a compromise with its backbench rebels.

In 1907, the law was changed to permit quick and easy opt-out by parents. Vaccination of all babies against smallpox remained theoretically compulsory until 1946, but in practice, it was now optional. A five-decade-long campaign, in the streets, the courts and finally parliament, had resulted in victory for the opponents of vaccination.

This is a sobering story for those of us who are researchers, medical professionals or public health activists campaigning against the spread of vaccine hesitancy in the modern world.

The success of vaccination in saving millions of lives, not just from smallpox but a host of other diseases, seems so obvious that the case scarcely needs to be made. And yet it does, as just a cursory glance at social, even at times mainstream, media will reveal.

In response to this tide of dangerous disinformation, vaccine advocacy work often focuses on issues such as the lack of public comprehension of scientific concepts of “relative risk” and “efficacy”, and the connections of the anti-vaccine activists to more general conspiracy theories and extreme religious or political movements.

The conclusion of many vaccine advocacy pieces is often that we must simply educate the public better while simultaneously cutting the flow of disinformation, yet this has often proved to be an uphill struggle. Why? Can vaccine advocates learn anything from the historic defeat of 1906?

Social media of the Victorian era

A recently published resource of Victorian anti-vaccination “street literature” seeks to contribute to this effort by providing free access to 3.5 million words from 133 documents, ranging from short pamphlets to longer publications over the period 1854-1906.

What the 133 sources have in common is that they were all produced for public consumption, designed to strengthen or maintain the beliefs of the converted while reaching out for new converts. Existing outside the conventional publishing industry, this street literature was the social media of the Victorian era.

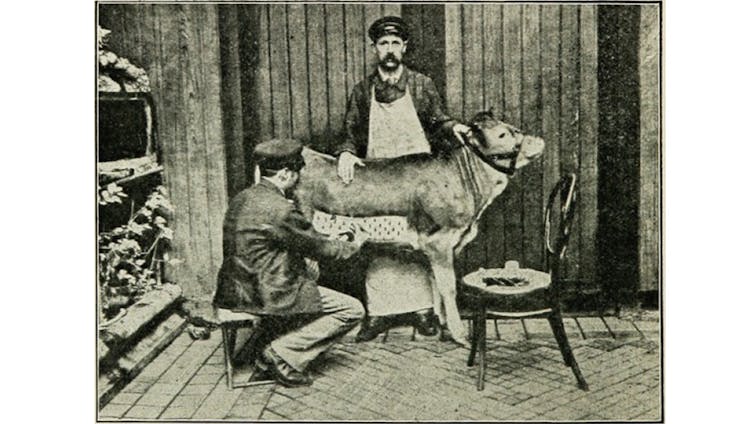

Wellcome Collection

Computational analysis of these texts reveals anti-vaccination themes that are very similar to those of today. For instance, doubts about the effectiveness of vaccines, what they’re made of and their safety, feature prominently.

Other common themes include complaints that civil liberties are infringed by compulsory vaccination, alongside conspiracy theories of government cover-ups, general distrust of the medical profession, and an orientation towards alternative medicine.

What changes is the detail. For instance, fear of the inadvertent introduction of syphilis, tuberculosis and skin diseases, as very occasionally happened in Victorian times, may be compared to the blood clots issue with the COVID vaccine.

Other more spurious scare stories, such as an association between vaccination and tooth decay or mental illness have their parallels in the discredited autism claims of the present day. Likewise, modern conspiracy theories about big pharma have their Victorian parallel in allegations of medical profiteering from vaccination fees.

This study of the Victorian anti-vaxxers shows us that there are indeed recurrent fears more than two centuries old. But it also teaches us that some of the motivations of vaccine hesitancy stem from social, political and religious beliefs that are equally deep in time and often deeply held.

Wellcome Collection

For example, William Tebb, one of the most prominent anti-vaxxers of Victorian times campaigned with equal energy on a whole raft of causes, from women’s suffrage to the abolition of slavery via vegetarianism, animal rights and mystical religion.

For Tebb and many of his followers, these were intimately connected causes. To reach the root of the problem, we need to untangle these connections in sensitive ways that go beyond conventional public engagement.

![]()

The project described in this article is funded by the UK Economic & Social Research Council.

Chris Sanderson received funding from the UK Economic & Social Research Council for this project.

Alice Deignan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.