On September 21, the UK government’s Science Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) published a document calling for a national circuit-breaker lockdown to curb the steadily increasing cases of COVID. The Sage scientists warned that “not acting now to reduce cases will result in a very large epidemic with catastrophic consequences in terms of direct COVID-related deaths and the ability of the health service to meet needs”.

Instead of heeding the warnings of their own scientists, the government instead solicited the fringe views of “experts” who advocated for controlling the effects of the virus with less restrictive measures, while shielding society’s most vulnerable. The result being that the government tried to limit the impact of the disease with a series of light-touch restrictions, including the original three-tier system introduced in the middle of October.

By the end of October, under these measures, the virus had spread to such a degree that the situation in the UK had become untenable. A national lockdown to control the spread of the virus became unavoidable. News of these imminent restrictions was leaked to the press almost a week before the lockdown came into force.

Springing a leak

At the time, the chairman of the Police Federation of England and Wales, John Apter, suggested that the leak would cause confusion and encourage “some to make the most of their pre-lockdown time”. But is this how things actually played out?

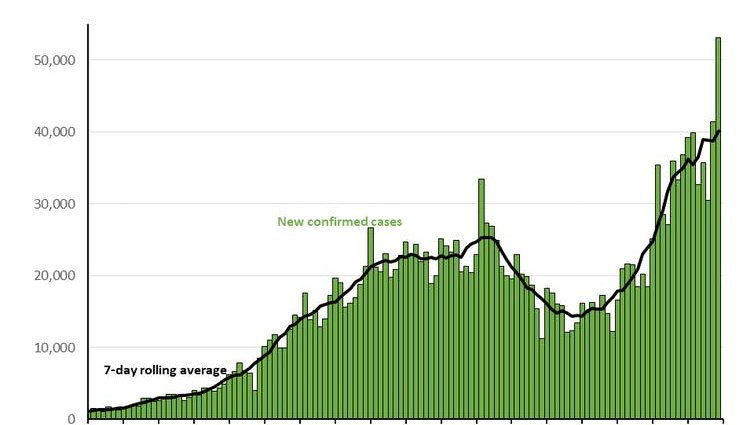

A new study, that has yet to be peer reviewed, attempts to answer this question. The analysis looked at case figures from across 315 local authorities. The publicly available data shows that in the ten days leading up to the national lockdown, there was a stagnation of cases. This was then followed by a sharp rise during the first week of the lockdown until its peak on November 12. Subsequently reported cases declined almost until the end of the lockdown at the beginning of December.

Credit: Kit Yates, University of Bath and Independent SAGE.

From the case data, the authors calculated a reproduction number (commonly referred to as R – the average number of people an infected person will pass the disease on to during the course of their infectious period). Their calculations seemed to suggest that while all three tiers brought down the reproduction number from around October 20, it then rose again in the five days before the lockdown was implemented in tiers 1 and 2. The authors conclude that the leaking of the lockdown plans before its implementation led indirectly to a surge in infections.

Far from definitive

While it’s tempting to believe that the leak was the sole cause of the infection surge at the start of the lockdown, this explanation is overly simplistic. The evidence provided by the authors is far from definitive. The official government announcement was made on the Saturday after leaks on the Friday night meaning the leak itself had limited impact (although it’s unclear to what degree the timing of the government’s announcement was influenced by the leak). Several other influences may also have been at play in the weeks leading up to the lockdown.

To understand the peak in cases during lockdown, we should consider the reasons for the plateau in cases in the fortnight leading up to it. In part, this may have been a result of tier 3 bringing down cases in the worst affected areas. Certainly, there was evidence to suggest that tier 3 was bringing down case numbers on Merseyside before the lockdown was instituted. The stagnation in cases might also have been a result of behavioural change as people saw the increasing hospitalisation and death figures reported in the media and decided to limit their mixing.

Perhaps the most compelling argument to explain the levelling off of cases is the staggered half-term break. Sage has suggested on many occasions that schools contribute significantly to the reproduction number. Remember, roughly speaking, that it takes somewhere between five and ten days beween people being infected and their positive tests being reported. A flattening of reported cases between October 23 and November 7 seems to agree nicely with the staggered half term across the UK from October 17 to 31. At least part of the spike in reported cases that occurred on November 12 might then be explained by the return of schools in the three days before the lockdown was implemented.

In reality, a combination of factors probably led to the spike in cases during the second lockdown: the return of schools, the leaking of the government’s plans and the five-day hiatus between the official announcement and the lockdown itself.

With just over 24 hours between the announcement and its implementation and with most of the country already under relatively tight restrictions, we can hope that any behaviour-induced rise in cases might be avoided as we enter our third national lockdown.

![]()

Christian Yates does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.