Nobody has officially claimed responsibility for deploying the satellite-controlled machine-gun with “artificial intelligence” used to assassinate Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh in Tehran at the end of November. But you would get fairly short odds were you to take a bet on it being the Mossad, Israel’s aggressive – and notoriously inventive – foreign intelligence service.

Israel has been carrying out what it calls “targeted killings” ever since its foundation in 1948. In his book, Rise and Kill First, leading Israeli journalist Ronen Bergman estimates the number of targeted killings at approximately 2,700.

Israel’s intelligence agencies are renowned for the inventiveness of their assassinations. Wadi Haddad, the director of foreign operations of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), was murdered in 1978 with poison in his toothpaste. Yahya Ayyash, “the Engineer” who masterminded a number of Hamas suicide bombings on Israel, was killed by an explosive charge placed in his cellphone in 1995.

Imad Mughniyeh, Hezbollah’s chief of staff, was killed by a car bomb in Damascus in February 2008. According to Bergman, the Israelis might have tried to kill Iranian general Qasem Soleimani with Mughniyeh, but only had US permission to kill Mughniyeh.

But, of course, it’s not just Israel which disposes of its foes via extra-judicial killings. We are living in the greatest-ever age of assassination as states, fearful of the twin threats of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction, are using increasingly sophisticated intelligence to track and kill dangerous people and deprive other states of dangerous knowledge.

New technology

The modern era of assassination began on 9/11 when the US realised how exposed it was to mass casualties from terrorist attacks on its soil. The “war on terror” took both crude and more subtle forms, the former being the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the latter being an airborne assassination programme enabled by new technology.

The drone has been a very effective assassin of terrorists. The first killings by drone took place in Yemen in 2002 – and, by the end of 2013 US drones and aircraft had killed between 719 and 929 people in Yemen alone. Meanwhile between 2004 and the end of 2013, the number of people killed by drone in Pakistan was between 2,080 and 3,428.

Special forces have been used to kill key targets such as Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan in 2011 and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Syria in 2019. In finally killing Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani in a drone strike in Baghdad in January 2020, the US took the radical step of eliminating a key state actor it considered to be a terrorist. The killing was deemed unlawful by the United Nations.

Russian president Vladimir Putin has also been ruthless, particularly when it comes to eliminating political foes. The attempted murder, by nerve agent, of former intelligence officer and British spy Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, south-west England, in 2018 and the successful murder of former Russian intelligence officer Alexander Litvinenko by polonium-210 slipped into a cup of tea in a London hotel in 2006 are merely the most high-profile killings in a chain of assassinations during Putin’s presidency. Among his victims have been opposition politicians and journalists, as well as veteran fighters from the bitter war in Chechnya who had been designated as terrorists by Moscow.

Preventing proliferation

Since the 1940s, the world’s leading powers have tried to prevent their enemies from developing weapons of mass destruction. Assassination to prevent the development of these technologies was pioneered by Britain in the second world war. One night in August 1943, the Royal Air Force bombed the German missile development and testing site at Peenemünde, on the Baltic. The RAF targeted the living quarters of the scientists, engineers and technicians with the aim of killing as many as possible. Approximately 130 German scientific workers were killed in the attack.

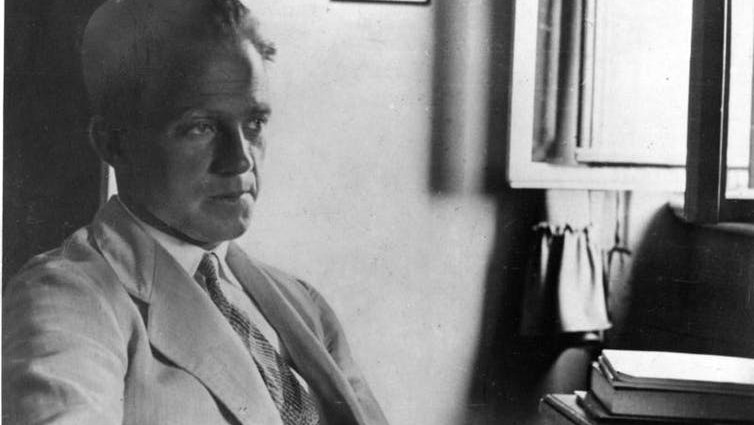

Britain and the US also feared that Nazi Germany might be developing an atomic bomb. In 1944 an American agent was dispatched to Switzerland to attend a lecture by Germany’s leading nuclear physicist, the Nobel Prize-winning Werner Heisenberg.

German Federal Archives, CC BY-SA

The agent was armed and had orders to assassinate Heisenberg if anything the physicist said indicated that Nazi Germany was close to developing an atomic bomb. In the event Heisenberg’s lecture gave no hint of this, which is why he survived his visit to Switzerland.

Israel has also used assassination to try to prevent its neighbours from developing missiles and nuclear weapons. In the 1960s, it tried to obstruct Egypt’s missile development project by murdering German engineers working on it. In 1980-1981 scientists and engineers working on Iraq’s nuclear weapons project were murdered while outside Iraq.

In 1990 the Israelis killed Canadian scientist Dr Gerald Bull, who was manufacturing for Saddam Hussein a “supergun”, the largest cannon ever assembled, which would have fired rocket-assisted projectiles thousands of kilometres. Bull’s murder ended the project.

Since 2007 Israel has tried to kill Iranian nuclear scientists: four have been assassinated, and an attempt made on the life of a fifth. Israel has never accepted responsibility for the assassinations but is universally thought to be behind them. Regardless, killing a small number of scientists won’t stop the project.

Assassination is as old as politics itself. But the increase in terrorism and the spread of the technology and know-how for the development of weapons of mass destruction are increasing its use. It is inevitable that states will resort to the assassination of individuals or groups of people they regard as dangerous.

![]()

Paul Maddrell is the author of Spying on Science: Western Intelligence in Divided Germany, 1945-1961 (Oxford University Press, 2006).