Violence has engulfed northern Ethiopia and, as usual, it is the civilians caught in the middle of this bitter ethnic conflict who are paying the highest price. Amnesty International reported on November 12 that a brutal massacre had taken place in the town of Mai Kadra in the northwestern province of Tigray. Scores – maybe hundreds – of people, described by Amnesty as seasonal labourers, were killed with knives and machetes.

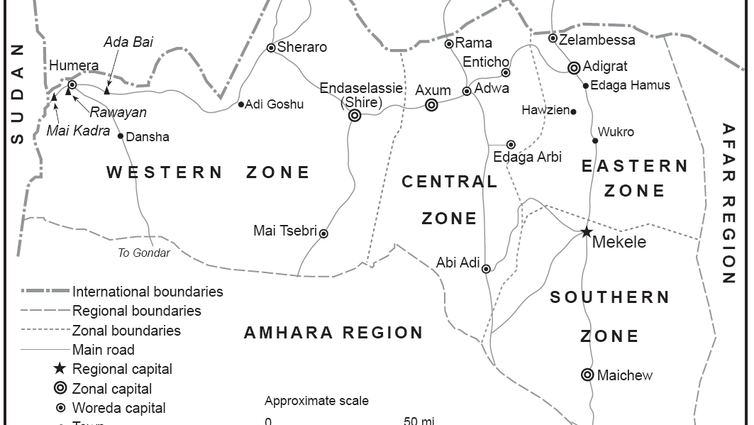

Fighting has also been reported near the border town of Humera where the Ethiopian army is understood to have wrested control of the airport from the Tigray People’s Liberation Army (TPLF). So far an estimated 25,000 people have fled to Sudan, including from the Humera area, an area that can be seen as a microcosm of the tensions that are pulling at the complex ethnic fabric across Ethiopia.

Ethiopia’s ‘Casablanca’

Back in 1993, while I was casting around looking for potential PhD research sites, a friend and colleague recommended I go to Humera, a town in the far northwest corner of Ethiopia. “It’s like an Ethiopian Casablanca,” he told me. I duly went to check it out. What I found held not so much the mystique of an old Islamic city but a bustling community of Tigrayan former refugees who had recently been repatriated after a decade in camps in eastern Sudan where they had sought refuge during the civil war that raged in Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991.

Originally highlanders, they were resettled into the fertile lowlands around Humera with the expectation that they would become smallholder farmers, supplementing their incomes working on the commercial sesame and sorghum farms in the area. Humera itself was a war-ravaged, dusty town that was just coming back to life after years of neglect. Remnants of the civil war could still be seen: in the walls of buildings that had been pockmarked by bullets and shrapnel, the carcasses of old abandoned tanks, and a local administration that was largely run by the former cadres of the TPLF, as a civilian administration had not yet been installed.

Although they were repatriating to Ethiopia from Sudan, the Tigrayans were not returning to their highland communities of origin. They were settled by the new regional administration into an area of northwest Ethiopia that had once been part of the Gondar province, but had been newly incorporated into the Tigray region in a process of redistricting that took place as soon as the Tigrayan-led government took power in 1991.

Repatriating 25,000 Tigrayans to these western lowlands became a way of laying claim to the land. Most were settled onto plots that had made up the unsuccessful state farms under the Marxist “Derg” government that had controlled the area from 1974-91 in the areas known as Mai Kadra, Rawayan and Adabai.

Life in the first years for newly repatriated refugees was difficult. They had to rebuild their lives from virtually nothing and learn to farm new crops using different methods than they had been accustomed to in their original homes. The Tigray region was faced with enormous post-war reconstruction needs, and many of the returnees in these three sites felt that they had been forgotten by the regional authorities once they returned. They received only meagre food and cash assistance for the first few months after returning and then were expected to become self sufficient. Gradually, however, people came to think of this place as home.

Laura Hammond, Author provided

At first, people in the local area got along with each other reasonably well. Amhara, Tigrayan, Welkait and other ethnic groups coexisted peacefully. The strongest resentment to the redrawing of regional boundaries to incorporate the area into Tigray region seemed to come from further away – from the city of Gondar a day’s drive to the south and the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa in the centre of the country. In these places the symbolism of shifting regional boundaries and seizure of land fed into a growing narrative of resentment against the Tigrayan-dominated central government.

Explosion of violence

These tensions have escalated over the years. The Humera area was largely isolated by the Ethiopia-Eritrea border war which lasted for two decades from 1998 to 2018. The main route for transporting sesame, its largest cash crop, out of the area – through Eritrea – was closed, and the town’s location along the banks of the Tekezze River which separates the two countries in the west was within the militarised zone.

Since coming to power in 2018, Abiy Ahmed, the first Oromo prime minister, has made overtures to the Eritrean president, Isaias Afewerki, seeking to end the border conflict with that country and implement the peace treaty originally agreed in 2000. His efforts helped him secure the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize.

But internally he has been focusing his efforts on weakening the Tigrayan-led government. He has replaced the former ruling party with a new Prosperity Party, which the former Tigrayan leadership has refused to join. When national elections were postponed, citing the risks posed by COVID-19, the Tigrayan regional government went ahead and held their own election on September 9. The central government refused to recognise the results and declared its intention to install an administration of its own choosing, thereby ramping up the tensions between the centre and the region.

Read more:

Residual anger driven by the politics of power has boiled over into conflict in Ethiopia

The real losers in this political crisis are, of course, the civilians caught in the middle of the fighting. For the people of Humera and its surroundings, who fled civil war during the 1980s, then lived through the border war with Eritrea and are now again on the front lines, the fighting brings back the trauma of past wars and displacements.

The grievances of each side are real and legitimate. But the violence that is now spreading across Tigray and into Eritrea and neighbouring regions is not resolving them. It is only adding to them, heaping pain and outrage onto a dangerous bonfire that is already burning out of control.

![]()

Laura Hammond receives funding from the European Union. She is Team Leader of the Research and Evidence Facility for the Horn of Africa. She is also Global Challenge Leader for Security, Protracted Conflict, Refugees and Forced Displacement for UK Research and Innovation's Global Challenges Research Fund.