Pneumonia is one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases, killing around 2.6 million people a year. In severe pneumonia, the tiny air sacs inside the lungs become filled with so much fluid and pus that patients struggle to breathe. In many people, this is fatal.

Patients can deteriorate very quickly, which means treatment is often given based on the person’s symptoms without knowing the underlying pathogen causing the condition. Part of the problem is that it can take several days to culture a patient’s specimen.

Because of the slowness in getting laboratory results, doctors often give patients best-guess antibiotics, followed by a different antibiotic if the first course doesn’t work. Sadly, in many cases, none of the antibiotics work and, in some cases, they can even harm the patient.

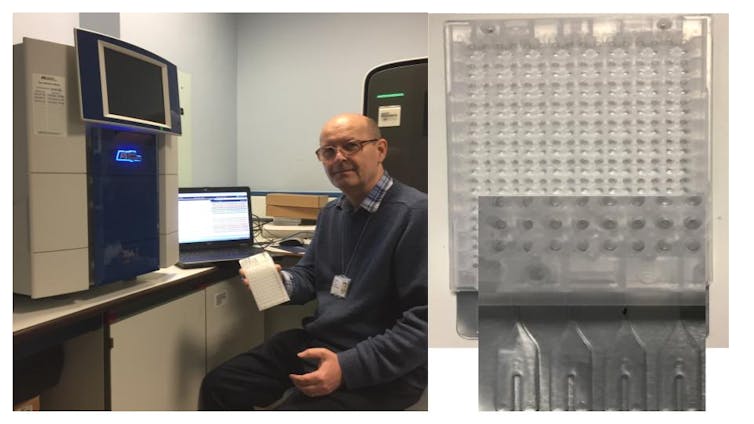

A new, cheap and rapid diagnostic system, developed by scientists (including co-author of this article, Andrew Morris) at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, England, could transform pneumonia care. An early trial of the diagnostic, conducted in the adult intensive care unit at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, showed that it can identify the pathogen responsible for severe pneumonia in patients on ventilators in just four hours. This compares with 61 hours needed to turn around a result using conventional culturing methods. It can also detect bacteria known to cause pneumonia often not picked up with conventional methods.

Lara Marks, Author provided

The new test uses what’s known as an array card. It contains tiny wells loaded with DNA sequences that match those of common microbes that cause pneumonia. If that DNA sequence is present in a patient sample, the array card amplifies it so that it can be detected.

The card includes genes from 52 respiratory pathogens commonly found in ventilated patients with pneumonia. Many different microbes can cause pneumonia. This includes viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 and flu as well as bacteria and fungi. A number of things determine which type of organism causes the disease, including where the patient picked up the disease – in the community or in a hospital – and the condition of their immune system.

Encouragingly the array card’s fast turnaround of results had a measurable effect on the choices ICU doctors at Addenbrooke’s Hospital made. Over half of the doctors changed their antibiotic prescriptions, with most changes leading to fewer antibiotics being used.

The team also tested the diagnostic in patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19, by loading sequences for the virus on to the array card. It proved very helpful in picking up secondary bacterial and fungal pneumonia in patients on ventilators. Patients with COVID-19 were found to be highly susceptible to these secondary cases of pneumonia, many of which were caused by hard-to-treat multidrug-resistant bugs.

Customisable

The array card is customisable. Single targets can be added or modified without having to re-optimise the entire panel. The team chose to target genes based on their local experience with pneumonia and antibiotic resistance.

The array card diagnostic is now integral to the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in the ICU at Addenbrooke’s Hospital. It has proven particularly useful for separating patients who have the virus from those who do not. This has helped to improve safety on the ward and free up beds and nursing staff.

The developers of the test hope to roll out the array card system globally. One of its attractions is that it can be quickly adjusted to take account of the different pathogens in different locations, as well as different patterns of drug resistance. This is vital for more precise antibiotic treatment and preventing the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

For those admitted to intensive care with pneumonia, the risk of dying is high, between 15% and 50%. Many who survive are also often left with chronic ill health, including weakened muscles and heart problems. The speed and completeness of a patient’s recovery depend a lot on their age and the pathogen that caused their infection.

Thankfully, there is now a test that can rapidly identify the pathogen so that effective treatment can started sooner. The new test is particularly important because pneumonia remains a stubbornly persistent disease which imposes a major burden on healthcare resources. Pneumonia is the most common secondary infection patients acquire when in ICU. A large proportion of pneumonia acquired in the ICU is linked to mechanical ventilation.

![]()

Lara Marks has received funding from the UK Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Andrew Morris receives funding from the Wellcome Trust.