As the US election campaign nears its end point, one thing about the result is certain: a lot of people won’t vote. Turnout at the 2016 US presidential election was only 60.1% – even without a pandemic. In 2020 there is a risk that COVID-19 will further undermine turnout.

The US is not alone and not the worst. Turnout at the 2016 Haiti presidential election, held only weeks after Hurricane Matthew, was 17.8%. The 2019 presidential election in Afghanistan, delayed because of technical problems, hit 9.6%. Actually, the US is pretty much in line with the global average of most recent presidential elections at 59.8%.

The main problem is that there is a major difference in who votes and who doesn’t, as we demonstrate in a new book. Our analysis of 55 countries reveals turnout is lower among women, younger voters, less educated citizens and poorer voters. Low turnout rates are also an issue among people with disabilities and among ethnic minorities.

This means that an election winner often enters office with a policy agenda based on the interests, hopes and dreams of those that made it to the polls – not those who didn’t.

Read more:

Trump’s encouragement of GOP poll watchers echoes an old tactic of voter intimidation

Who doesn’t vote

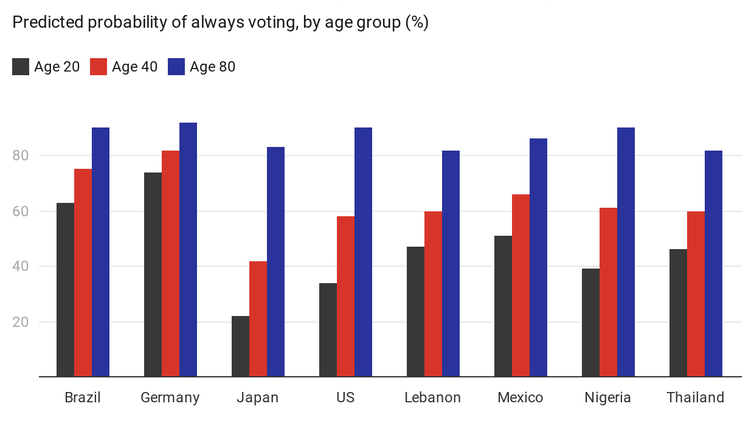

The nature of these turnout gaps varies enormously by country. The US has enormous gaps by education, age and between lower and upper income categories. The difference in the predicted probability of voting between citizens with less than a secondary education and those with bachelors degrees stands at 39 percentage points. The voting gap between the over 80s and under 20s is as much as 56 percentage points.

CC BY-ND

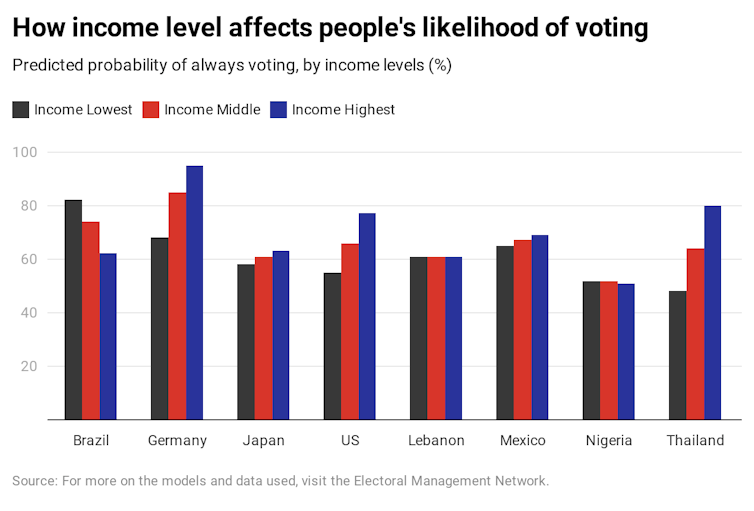

And when it comes to income, the richest have a 22 percentage point lead over the poor. In other words, these citizens, who are more likely to vote than their younger, less educated and less wealthy counterparts, are who decides elections.

Broadly similar patterns are found in Germany, Mexico and Japan. In Brazil, however, where there is compulsory voting, it’s actually poorer citizens that are much more likely to vote than those in the highest income group, who can perhaps afford the fine. In Nigeria, there is also a sizeable gender gap with women much less likely to take part in elections.

CC BY-ND

Pathways to exclusion

Politicians often wash their hands of these election inequalities by arguing that it’s an individual’s responsibility to vote. But while there is clear evidence that some voters are being systemically excluded, there are also remedies available that could act as proactive interventions to level-up democracy.

Violence and intimidation are the worst of these pathways to exclusion. This can be highly gendered in nature, for example when gangs of young men were paid as party agents to threaten supporters of opposition candidates in Uganda. Instances of men shouting at women are also found in English polling stations. Voters can also be deterred digitally. A recent Channel 4 investigation found 3.5 million Black Americans were profiled in the 2016 presidential contest by the Trump campaign, with the aim of suppressing turnout through targeted Facebook ads.

Election laws can also prohibit participation. Although not included in most turnout statistics, many citizens aren’t entitled to vote because of prior criminal convictions or because they are overseas.

Citizens can also be formally enfranchised, but informally discouraged to vote. While voting is compulsory in some countries, it is optional in others, despite evidence that compulsory voting can give better representation to the poor.

Onerous voter identification requirements, used in pilots in the UK, led to many citizens not being able to vote because they couldn’t provide identification on the day – or they refused to out of principal. The design of polling stations and voting practices can likewise disadvantage citizens with disabilities.

Read more:

Voter ID: our first results suggest local election pilot was unnecessary and ineffective

Uneven resourcing and management of elections can also exclude some voters. Voter experiences at polling stations were uneven across the 2008, 2012, 2014 and 2016 US elections. Compared to white, Hispanic, and Asian voters, African American voters were most likely to report waiting more than 30 minutes or experiencing a problem with the voting machine or their voter registration.

Incomplete electoral registers, which tend to miss poorer, younger and Black and minority ethnic citizens more than others, have lead would-be voters to be turned away from UK polling stations during local elections.

Making elections more inclusive

Turnout gaps represent a major threat to political equality. Measures which have been successful at addressing these gaps include giving votes back to disenfranchised citizens such as those denied because of past criminal convictions. Automatic or same-day voter registration to prevent citizens being unable to vote on election day, and compulsory voting, can also increase overall turnout.

Research also shows that better resourced electoral officials can prevent queues at polling stations and boost voter confidence in the process. Better training for poll workers can prevent citizens in some geographical areas being more likely to be asked for voter identification. Opportunities for voting by mail can build political inclusion for those with disabilities. And ensuring that elections are externally observed can also help prevent irregularities.

Politicians need to take these reforms forward around the world to make sure as many people as possible are able to exercise their democratic rights.

![]()

Toby James' research has been externally funded by the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust, British Academy, Leverhulme Trust, AHRC, ESRC, Nuffield Foundation, SSHRC and the McDougall Trust.

Holly Ann Garnett receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Defence Academy Research Programme.