If you have been following the media coverage of the new vaccines in development for COVID-19, it will be clear that the stakes are high. Very few vaccine trials in history have attracted so much attention, perhaps since polio in the mid-20th century.

A now largely forgotten chapter, summer polio outbreaks invoked terror in parents. Today, restrictions on gatherings and movement in the efforts to control COVID-19 have been a huge strain on society, but in the 1950s, parents locked their children in stifling hot buildings during the summer with windows sealed shut because they were terrified polio would somehow seep through the cracks in the wall.

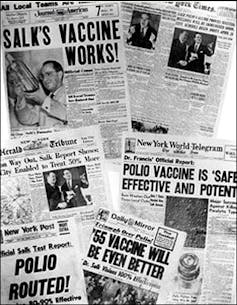

The development of the polio vaccine in the US in 1955 was a moment of global celebration. Reaching that point involved millions of citizens raising funds to develop the vaccine, political goodwill by the bucket-load and a driven public-private scientific collaboration, with scientist Jonas Salk at the helm. Children across the US were enlisted in one of the largest clinical trials in history.

March of Dimes/Wikimedia Commons

Clearly, setbacks and challenges occurred along the way, even once the vaccine was being rolled out. In a shocking episode called the “Cutter incident”, a failure in making and inspecting the vaccine by a California-based firm called the Cutter Laboratories led to children getting polio from the vaccine, which contained viable poliovirus.

The incident led to a major tightening of federal regulations to ensure production safety. It also resulted in new laws being passed that prevented vaccine manufacturers from being sued. (The fear was that drug manufacturers would not want to develop vaccines without being protected by the law.)

A lack of urgency for vaccine uptake quickly set in. It is taken for granted that children are vaccinated routinely, but this acceptance took time. In the early era of vaccination, it was a tool against epidemics and people expected to be vaccinated during an outbreak. Through health education and communication, funding of immunisation services, and political support across party lines, vaccination was promoted as a central pillar of a public health globally.

Promise of an Aids vaccine

When the next big plague of the 20th century hit – Aids – naturally it was vaccination that would be looked to. Within a short time of scientists confirming HIV was the cause of Aids in 1984, the US health and human services secretary, Margaret Heckler, announced that a vaccine would be ready in two years. The high expectations and hope instilled in vaccination were not surprising, particularly following the eradication of smallpox from the planet in 1980. However, an Aids vaccine proved to be unattainable.

Unfortunately, many aspects of HIV infection make it very difficult to develop a vaccine. Instead, it has been antiretrovirals – a group of drugs that inhibit various steps in the HIV replication process – that have proved to be the most effective strategy for treating Aids.

The stigma of Aids was also an inhibitor for controlling the disease. Health officials at the beginning of the Aids crisis coyly referred to the transmission being through “bodily fluids”, instead of specifying blood and semen. This lead to misunderstandings about the disease being spread through touch.

New pandemic, same problems

Today, COVID-19 is the latest public health crisis that cannot be separated from politics and society. Fear of this disease, and whether it is taken seriously and seen as important to protect against, will play a major role in the support and uptake of a vaccine.

Most people want to return to a “normal life”, and a vaccine is the most reliable way to achieve this. However, the public’s desire for a vaccine is balanced against concerns about the speed of vaccine development, wariness about new types of vaccines, and mistrust of pharmaceutical companies, governments and the “health establishment”.

Public action in communities has been evident throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, in neighbours supporting the elderly and those unable to leave their homes by delivering groceries and medication, as well as compliance with government health messaging, and willingness to take part in medical trials. But national political stakes for a vaccine remain high with politicians using “vaccine deals” to bolster popular support and win elections.

The acceptance of vaccines is fragile, so when leaders promote their country’s vaccine with clear political motivations, it can knock the public’s confidence and draw intense scrutiny. As with the polio vaccine of the past, the world is watching.

![]()

Samantha Vanderslott receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the New Venture Fund. She is also a steering committee member for the Vaccination Acceptance Research Network (VARN).