When Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced that he would not be going ahead with his plan to scrap the top rate of tax in the UK, he claimed that he had done so because “he listened” to the public. There had indeed been a widespread outcry over his plan, set out in his ironically named “mini-budget” on September 23, but the reversal is more likely because the Conservative government’s own MPs would block its passage through parliament by voting against it.

Some of this resistance was probably a genuine belief that the measures were wrong. But a more likely explanation is that many MPs fear that their seat (and control of government and parliament) would be in danger if they went along with the idea.

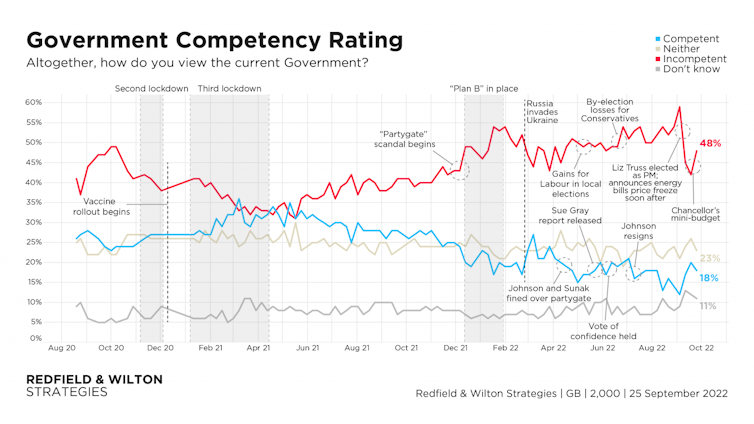

That fear is warranted. Recent polling provides very few glimmers of hope for the Conservative party. The mini-budget is merely a chapter in a much longer story. It was already clear in July that the darkening perceptions of the Conservative party were unlikely to be improved by anyone – and particularly not Truss (who is an ally of Boris Johnson).

Since then, Labour has been buoyed by a successful party conference. All told, the reversal (or postponement) of the cut to the top rate of tax is likely to do little for the public, even if it takes the heat off the furore.

What the polls say

The headline polling figures, which reveal who people would vote for if there was an election tomorrow (or their response to a question to that effect), show an average of a 24 percentage point lead for Labour.

Some individual polls put Labour ahead by 30 or more percentage points. In truth, these are likely to be over-generous. But even the most pessimistic poll for Labour, the lowest lead (Redfield and Wilton, which gives the opposition a 17-point lead) would still probably deliver a landslide election victory.

Polling since then indicates these large leads are not pure outliers. It should be noted that this is not a sudden change. Labour has been growing in strength for months, ever since the “partygate” scandals.

The difference in figures is likely due to how the companies deal with voters who answer “don’t know”. Some just remove them from the results, while others distribute them proportionally to the other parties. It may also be a function of how different pollsters treat the likelihood of voting at all. In any case, they all show a significant lead for the opposition.

It gets worse …

Vote intention polling doesn’t tell the whole story. Often when we look at the bigger picture, other figures look more positive for the Conservatives. That, however, is changing. And this is a significant point of concern for the government.

The economy, for example, is by far the most important issue for voters, with healthcare a close second, and Labour are much more trusted than the Conservatives to deliver on both (68% think the Conservatives are managing the economy badly). In fact, Labour is now trusted more than the Conservatives to deliver on almost any policy.

Given that the Conservatives number one campaign promise is to deliver economic growth, it is bad news for them that the Labour Party is seen as better on this issue. With an economic turnaround unlikely in the immediate future, this is unlikely to change.

Also, there is a lot of evidence in political science that personal economic fortunes are an important factor in who people vote for. People don’t often vote for governments that have, or will, make them worse off.

The polling around the two leaders is also positive for Labour. Unlike at the start of September, Keir Starmer has a solid lead over Liz Truss when people are asked to choose who would make the best prime minister – 44% answer that he would, versus 15% for her.

Unsurprisingly, only 15% of those polled think Truss is doing “well” as PM, and 65% think she is doing “badly” (60% also think Kwarteng is doing badly as chancellor). The small hope for Conservatives is that many people are unsure, 37% regarding who would make the best PM and 19% regarding who they’d vote for. This means that there’s a sizeable electorate that could still be moved.

Redfield & Wilton

The polling does, however, show that a substantial minority of those who voted Conservative in 2019 would now vote for Labour. While previously there was little movement between the two parties (suggesting the Conservatives were still holding firm), this indicates that a migration is now happening.

The hope the Conservatives will have – aside from their projection that the policies will materially improve people’s lives after a difficult winter – is that there are still many people who are not convinced by any party.

U-turn if you want to

If Kwarteng was hoping his tax U-turn would be enough to reverse these trends, he is likely to be disappointed. It might calm some of the furore, but it is unlikely to move the public. Most do not think it is a priority. It also does not solve the primary problem – a lack of policies to help people struggling with rising bills, rents and mortgages.

The U-turn is also likely to undermine Truss’s argument that she is a strong leader on a mission to change the country. Just a day before the U-turn, she said she was fully committed to the policy.

MPs and senior Conservative politicians speaking against the budget all contribute to the image (and reality) of a party in disarray. Many will now be left wondering: if this can be overturned by internal rebellion, what else is up for grabs?

There is a growing consensus among political scientists that trust in politics is at a crisis point. Trust in politicians and the government is made up of three key components: the idea that they are acting in your interest, that they are doing so competently, and that they are applying integrity to the task.

Liz Truss’s rise to PM was fuelled more than anything by a lack of integrity from Boris Johnson, accompanied by underlying concerns from the public about the Conservative party’s competence.

The new government may have now completed the trifecta by clearly stating whose interests they are serving in response to these crises. Truss has effectively admitted as much herself when she said she was prepared to “be unpopular” to get her way. The reaction to her premiership so far at least indicates success on that front.

![]()

Hannah Bunting receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Daniel Devine receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)