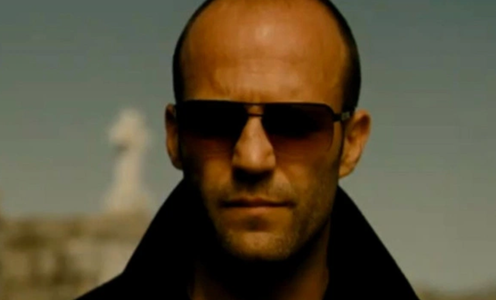

Millennium Films

Vividly portrayed in films from The Godfather to The Sweeney, the idea of criminal enforcement using threats, intimidation, assault and murder has long been an established underworld practice.

Despite the widespread cultural fascination with this shadowy part of society, there is little in the way of academic work that explores the role of enforcers.

My latest research with colleagues from Scotland and the US consisted of interviewing underworld figures from two parts of the UK – the West Scotland and the West Midlands, to further explore the nature and extent of this phenomenon.

In popular culture, the criminal enforcer conjures up images of machismo, allure, brute force and professionalism. In the fictional world, enforcement activities like debt collecting or extortion seemingly take place within the night-time economy, in pubs, clubs and casinos.

Also in media portrayals in news and on television, the preferred mode of communication seems to be violence – a constant presence in organised crime. My previous research on organised crime argues that violence can be used strategically by a crime outfit to start, maintain or advance a criminal enterprise. But to what extent is this the case for enforcement out on the streets of our towns and cities?

Becoming an enforcer

The West of Scotland and West Midlands have long histories of organised crime – both places are major hubs for illicit drugs. Through a comparative study we gained extensive insights into a number of areas including how people become enforcers; how contact is made between all parties involved; the costing arrangements; and the degree of planning involved.

In the study, a criminal enforcer was defined as any member or associate of a criminal organisation who acts illegally to achieve his ends. Essentially the enforcer is someone who settles a dispute to get “justice” for his employer, such as a debt that is owed.

It’s 100% social. You need to have that name. Everybody needs to know that you’re the person who collects the debts. Often, you gain that criminal reputation and respect from the work that you’ve put in, the prison time that you’ve done.

This was a response from John, an ex-military private investigator, when asked whether strong social connections are required to be a successful enforcer. Social capital, according to John, underscores the saying: “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know”. So this view is not exclusive to the legitimate world and makes clear the importance of being known and being seen on the streets when it comes to underworld enterprises.

Shutterstock

The economics of enforcement

Researchers who have explored the economics of crime and punishment tend to examine how offenders calculate things: the practicalities and money offered by a legal income; the income potential of illicit methods; the probability of being arrested for criminal behaviour and the likely punishment if convicted.

Aaron, who has previously worked as a debt collector for several crime groups, alludes to the good money that is associated with enforcement:

… Sometimes the lender will tell you to get back his money and you will get a percentage. I’ve been involved in situations where individuals have had to pay back the money with interest. In these cases I’ve been told by the lender to take a percentage from the money he’s owed and whatever else he’s charged on top.

Interestingly, Aaron did not seem to factor in the probability of being arrested in his calculations. This should not be mistaken for foolishness, as enforcers are rational and sophisticated in their planning and carrying out of illegal work.

Planning and acting

Popular culture often portrays enforcement as a physically violent endeavour. According to Theo, a convicted offender, violence is not necessarily good for business:

I’ve been part of situations where it’s been a “criminal figure” who dealt with a legitimate company that owed him money… I didn’t go in with tools [weapons]. It’s because I was dealing with normal nine-to-five people, who would happily call the police… You’re better off reasoning with them and having a conversation.

Theo’s approach to violence is dependent on the circumstances of the debtor. Enforcement, in relation to debt collecting, is not a process that is exclusive to underworld operatives. His approach of “reasoning” with normal everyday people (as opposed to other criminals) implies logic, which is much needed when retrieving owed money.

Overall, our study suggests that nuanced enforcement practices is an alternative form of criminal justice that is woven into the fabric of any provision of illicit goods or services. Yet, it is a criminal activity that is overlooked in national debates due to limited academic research.

Certain kinds of occupation often facilitate criminal behaviour like enforcing, such as a military background. Future research would help establish potential links between previous occupations and becoming involved in the enforcer business for organised crime, whether using lethal or non-lethal approaches. Clearly there is nuance there that is rarely explored in popular police and mafia dramas.

![]()

Mohammed Rahman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.