Aaron Hunter, Author provided

The English town of Lyme Regis is part of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. It was here in the 1830s that William Buckland, better known for the discovery of the first dinosaur, Megalosaurus, collected fossils with another pioneering palaeontologist, Mary Anning.

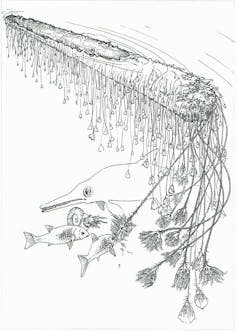

One of their discoveries was the remains of fossilised crinoids, sometimes known as “sea lilies”. Close relatives of sea urchins and starfish, these flower-like animals consist of a series of plates connected together in branches with a stem. The specimens from Lyme Regis, dating back to the Jurassic period over 180 million years ago, look like polished brass because they have been fossilised with pyrite (fool’s gold).

Buckland noticed that these crinoid fossils were attached to small pieces of driftwood we call lenses, which had turned into coal. He hypothesised that the crinoids had been attached to the driftwood while alive, and perhaps for their entire lives, possibly living suspended underneath it.

Crinoid fossil, Author provided

Modern crinoids don’t typically take such journeys, but we’ve since discovered fossilised examples of groups of floating crinoids. However it wasn’t clear whether these were really thriving colonies living on the driftwood or just short-term passengers. Now my colleagues and I have shown that such rafts could last for as long as 20 years, plenty of time for crinoids to grow to maturity and become full-time ocean sailors.

Buckland’s idea was initially seen as fantastical and the scientific world remained sceptical. Until, that is, the discovery in the 1960s of a truly spectacular group of fossils from Holzmaden, a village not far from Stuttgart, Germany. In among marine reptiles, crocodiles and ammonites, were giant colonies consisting of complete logs covered with hundreds of perfectly preserved crinoids.

The German professor Adolf Seilacher and his then student (now professor) Reimund Haude appeared to have resolved Buckland’s mystery. These floating rafts of crinoids did exist. This idea was strengthened by evidence that, in the Jurassic period, what is now Holzmaden had been a seabed that was uninhabitable due to low oxygen levels. The crinoids would have clung for life to these logs as there was no seabed for them to live on.

R. Haude, University of Göttingen

However, not all scientists agreed. One of the key questions asked was whether these log rafts could have survived for long enough for the crinoids to grow to maturity. This can take up to ten years, based on modern growth rates of their living relatives that can still be found at depths of around 200m.

A team of scientists from the UK and Japan led by myself decided to tackle the problem. We were motivated by groundbreaking research on Japanese crinoids by Professor Tatsuo Oji, that were kept alive in the labs at the University of Tokyo.

One of the key parts of the original theory was that any floating colony of crinoids would have grown until the population became too heavy for the wood raft to support it. The log would have sunk to the oxygen-free seafloor where the crinoids would then have become fossilised. However, research on living crinoid populations off the coast of Japan revealed that the animals would be too lightweight, even in large mature colonies, to cause a log to become overburdened and sink.

Model breakup

Our research then turned towards the wood itself. We established that the way to understand how long the colony could have lasted was to develop a “diffusion model”. This estimated how long it would take before the log would become saturated with water and fail.

The wood in crinoid raft fossils hasn’t been preserved well enough for us to know what species it comes from. So we represented it in the model with a composite estimate of trees we know existed in the Jurassic, such as conifers, cycads and ginkgo trees.

We found that the floating wood and its crinoid cargo would have been able to last for at least 15 years and maybe up to 20 years before the log would begin to sink or break up. There is evidence from museum collections of fragments of wood with entire, fully grown crinoids attached to them that could only have resulted from this kind of collapse.

Finally, we utilised a technique known as spatial point analysis developed by Dr Emily Mitchell, to plot the spaces between the fossils and work out whether the position pattern is ecological, environmental or both. This enabled us to estimate how this crinoid community might have looked on the log.

Royal Society

We found that the crinoids do indeed hang suspended underneath the driftwood, but clustered towards one end of it. Although difficult to observe in the original fossils, the pattern resembles that of other modern rafting species such as goose barnacles. They tend to inhabit the area at the back of a raft where there is least resistance, which can tell us the direction of travel of the colony across the ocean.

This research has now put beyond doubt that crinoid raft colonies could exist and survive for many years to grow to maturity and travel the vast distances across the Jurassic oceans. They are a deep-time example of similar structures we see in today’s oceans.

These exciting techniques are now being used by a new team to compare living populations on the sea floor to their Jurassic forebears. This could reveal how past changes in climate have shaped marine communities and will help scientists understand how such communities might respond to future challenges in an ever changing world.

![]()

Aaron W Hunter does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.