Sukhonosova Anastasia / Shutterstock

When you meet someone new in person, one of the first things you notice is how they speak – if they speak the same language as you or have a different accent. You’ll also notice if they use different dialect words or phrases to describe things.

Dialects can tell us lots about the history, culture and traditions of a place, a group of people or even an individual family – which is why my team at the Dialect and Heritage Project is launching the Great Big Dialect Hunt. Like the rest of the UK, England has a rich and varied dialect landscape, from the dialects of Cumbria and Northumberland in the north, to those of Cornwall, Kent and Sussex in the south. We are interested in hearing all of them, whether you come from a tiny village or a large city.

By capturing a snapshot of present-day usage in England, researchers will be able to ascertain the extent to which dialects are still used, how they vary across the country, and why they matter to people. The project will investigate whether dialects are shaped only by where we grow up and go to school, or if there are other factors in play, such as words inherited from family members, or adopted as people move from place to place or form new relationships.

What is a dialect?

The linguistic boundaries between a language and a dialect are much less distinct than might be imagined. As linguist Max Weinreich said: “a language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” Some languages are mutually intelligible and less distinctive from each other than some dialects. But typically, we think of languages containing multiple localised variants called dialects.

A dialect is a set of sounds, words, phrases and grammatical structures associated with a particular place or social group. Location is the most common definition – you may know (or be) someone who speaks Yorkshire dialect, for example.

An accent, on the other hand, is simply a way of pronouncing –- we all have an accent. When people talk about not having an accent, what they really mean is that their accent doesn’t “betray” their geographical origins.

Read more:

Why does the UK have so many accents?

Dialects can be found in both speech and writing, though are much more commonly encountered in spoken language. Oddly enough, many people who speak in dialect don’t read or write it, and vice versa.

Dialects can be a source of local pride, but they also underline differences. Many of us have had the experience of encountering unfamiliar words from other places, or using what we think of as an unremarkable expression – only to be met with blank stares and requests for explanation.

What dialects tell us

Dialects can tell us about society, history and movements of people. There are words with Old Norse influence in the Yorkshire dialect (such as “beck” meaning “stream”) because it formed part of the viking Danelaw – those parts of the country that were colonised by vikings during the Anglo-Saxon period.

The words “sneck” for “door latch” or “flit” meaning “to move house” are found as far apart as Scotland and Yorkshire. Why? Because both can be traced back to the Northumbrian variety of Old English, which straddled the present-day Scottish/English border.

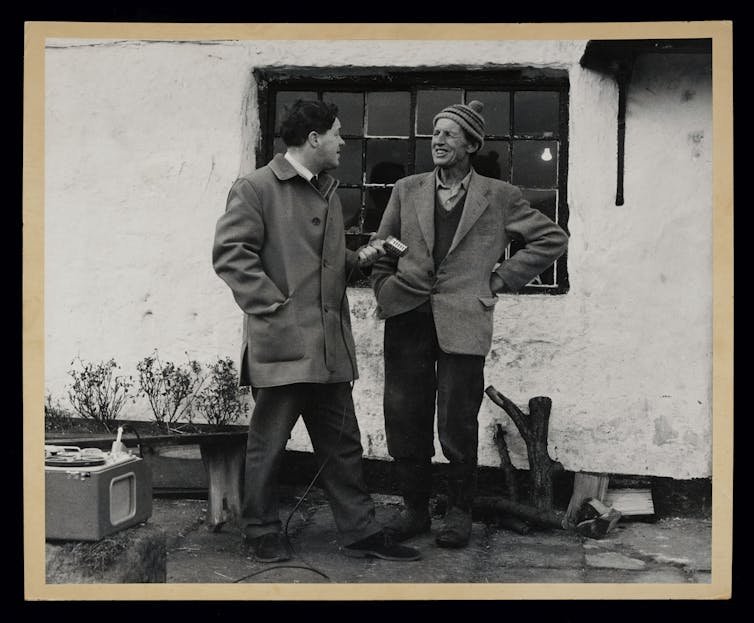

The Survey of English Dialects / University of Leeds, Author provided

Traditional dialect studies such as the Survey of English Dialects, which was carried out during the 1950s and early 1960s, used dialects as a way to learn about earlier forms of language. Researchers from the University of Leeds visited 313, mainly rural, village locations across England, interviewing two to three speakers in each place. They asked participants some 1,300 questions about the language they used in everyday life.

Fieldworkers were careful to select older speakers who, ideally, were lifelong residents, and likely to be “good” speakers of “traditional dialect”. The research methodology specified a preference for “old men with good teeth”.

Our research makes no such demands about age, length or place of residence, or the state of one’s teeth. We would like to hear from everyone –- young or old, long-term resident or recent arrival –- whether you think you use dialect or not. This is a dialect study for today and the way we live now, and a linguistic time capsule for the future.

Why dialects matter

There is something almost visceral about hearing someone use a word from your childhood, local town or village, or a familiar accent that immediately transports you to a specific time and place.

In addition to collecting present-day dialects, we are sharing historical materials (sound recordings, photographs, dialect fieldworkers’ notebooks, fascinating stories of life in times past) from the Survey of English Dialects and the Leeds Archive of Vernacular Culture with the communities from which they were originally collected.

Dialects are living heritage that we carry within us throughout our lives, connecting us to past and present, people and places. They are about who we are, our sense of self and identity, and where we feel we belong. As such, they deserve to be studied and celebrated, in all of their glorious diversity.

![]()

Financial support for the Dialect and Heritage Project has come from National Lottery Heritage Fund (£530,500), the University of Leeds’ Footsteps Fund and alumni donations (£110,000), and partner museums (£23,000).