Collective action is often the key to creating dramatic social or environmental changes, be it reducing pollution and waste, diminishing overfishing by sourcing alternatives, or getting more scientists to openly share their data with others.

Collective action, however, can involve social dilemmas. That’s because the choice to act altruistically might come at some personal cost. To deal with such problems, cooperation and communication are key. Now our new research, published in Rationality and Society, sheds some light on the best way to get people to cooperate in such situations.

In the world of economics, decisions about cooperation are often studied in laboratory games such as the prisoner’s dilemma or the public goods game. The public goods game is one of the best examples of a cooperative set up: participants have to secretly choose how many of their private tokens to put into a public pot, which everyone can benefit from.

The interesting aspect of the cooperative situation in this game, and many others, is that it exposes each member of a group to uncertainty, which is the fundamental source of the social dilemma. Even if an individual member might cooperate by sharing their resources, they can’t be sure if anyone else will. So, if you cooperate you are taking a chance, meaning the first move to cooperate can be viewed as altruistic.

It might be disappointing to realise that others might not cooperate. This may prompt some to opt instead to free-load, which is to cooperate less or not at all, but still benefit from the potential cooperative actions of others. The first move to do so is viewed as selfish by scientists.

So what do people typically do in such situations? It depends what other factors people take into account, for instance the social status they have in the group, as well as the type of resources they are giving up.

In reality, decisions of this kind are often made in situations that involve discussions with others. The communication aspect here can be crucial. Communication helps group members to size up the intentions of the others, and gives them a chance to persuade their peers to act cooperatively.

However, this presents another form of uncertainty. We know that people don’t always do as they say. For instance, they might be virtue signalling – talking in ways that promote themselves as virtuous and reputable, without actually intending to cooperate.

Talk is cheap

To look at the effects of communication on cooperation, we assigned 90 people to groups of five. Each member of the group had to perform a task which was tied to money – squeezing a hand grip device multiple times to get a small reward each time.

Each member of the group had a choice to make: either keep the money for themselves each time (free ride), or contribute it to the group pot (cooperate). Whatever money was in the group pot each time was multiplied by 1.5 – so half more than what could be earned individually.

Two other important elements of the experimental set up helped us to understand more precisely the influence of communication on cooperative behaviour.

Participants had to choose whether to cooperate under specific sets of circumstances. In the “possible virtue signaling” condition, each member had to state before they performed the task how many times they intended to share money they had earned, and were told that this information would be communicated to the rest of the group. In the “money in your mouth” condition, each member was told that the actual number of times they shared the money would be communicated to the rest of the group. In the “flying blind” condition, however, no information was communicated to the rest of the group.

fizkes/Shutterstock

Once every member of the group had performed the actual task, all five members entered into a group chat online where they could discuss the task, and the information (at least for two conditions) that was presented to them. After the group chat, they then performed the task again, and were each paid the amount that they had personally earned, as well as the amount earned by the group.

So what happened?

People were much more likely to cooperate during the “possible virtue signaling” and the “money in your mouth” conditions than in the “flying blind” condition. So, knowing that your intentions or actions would be passed on to the group made a difference. But how much of a difference was determined by what was discussed in the group chat.

There was a direct relationship between how much the group reached a consensus to cooperate, and how much they actually cooperated. In other words, when people said things that helped the group reach a consensus, they ended up acting cooperatively.

Our study suggests that avoiding phrases that indicate hedging and equivocation helps people cooperate. Being vague about the extent of your intended contribution, “I’ll give more next time”, and offering conditional contributions, “I’ll give more if everyone else does”, will fosters mistrust within your group and reduce people’s sense of obligation. Ultimately, this will hinder the group’s ability to reach an agreement to cooperate.

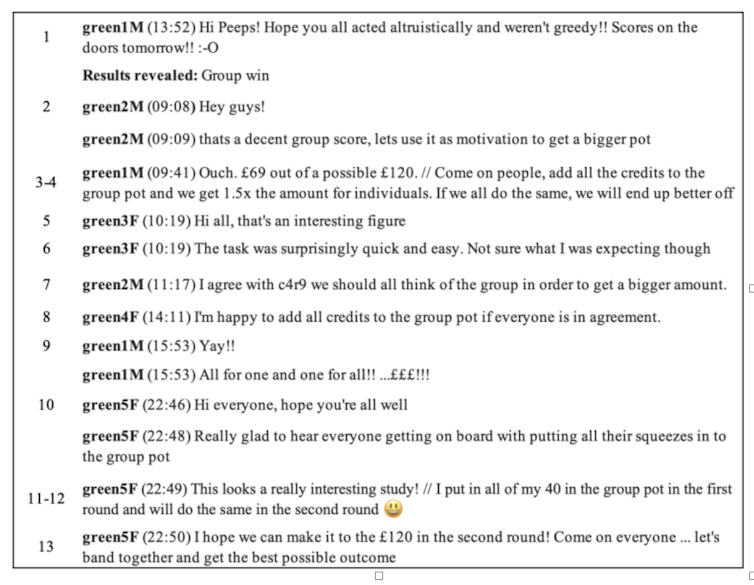

Author provided

A better approach, as can be seen in the example above, is to be explicit and specific with the promises you make about your contribution. It’s also important to pose a direct question to the entire group which asks about everyone’s intended contribution. This encourages each member to make a commitment, and if someone evades the question, it’s a useful signal.

The communication styles we use can also make a difference. Speaking in a way that signals solidarity and authority will strengthen the group’s collective identity and establish a norm to cooperate. Humour and warmth help too. On the other hand, we found that groups that used more formal and self-interested communication styles, such as those associated with the world of business and politics, were less cooperative.

In short, showing strong leadership through assertive statements, expressing encouragement through motivational phrases, and making people feel part of your group are good first steps in getting others to cooperate.

![]()

Magda Osman receives funding from: ESRC, Research England, British Academy, EPSRC, Wellcome Trust, Food Standards Agency, Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, Alan Turing.

Devyani Sharma works for Queen Mary University of London. She receives funding from the ESRC.

Zoe Adams receives funding from: ESRC and Queen Mary University of London

Agata Ludwiczak does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.