Omicron, the latest variant of concern, was discovered in samples collected on November 8 in South Africa. It rapidly replaced delta as the dominant variant in the country and now accounts for nearly 100% of cases in South Africa.

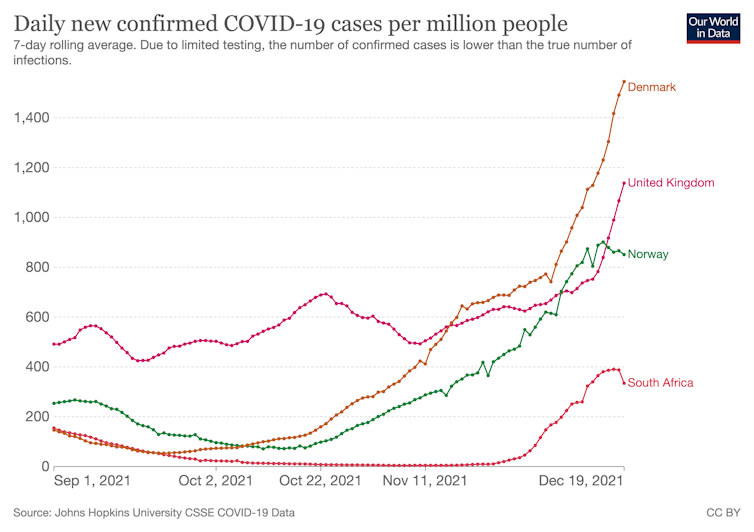

Since then, this latest “variant of concern” has since spread throughout the world and is surging in several countries, including the UK, Denmark, Republic of Ireland and, most recently, the US.

Two factors appear to contribute to its success: high transmissibility and its ability to evade the protection from vaccination. Omicron’s potential to overpower national health systems worries many public health experts and has led to some countries introducing strict control measures.

Dangerous situation

The UK is heading into the festive season in a dangerous situation. New omicron cases are doubling approximately every two days in some areas, including London. To put this in context, such a rapid spread has not been seen since March 2020 when the reported numbers doubled every three to six days in the absence of any restrictions or vaccination protection.

The current regulations – mandating wearing masks in the public, encouraging working from home and avoiding large events – reduce the transmission and deprive the virus of the opportunity to spread. Nearly 70% of the population have received two vaccine doses and over 40% have received a booster. These measures have been sufficient to stop the delta variant from spreading, but have so far failed to prevent the omicron outbreak.

The GISAID Initiative, https://www.gisaid.org/about-us/mission/

There is still substantial uncertainty regarding the future of the outbreak. However, the course of the omicron epidemic can be gleaned from what scientists already know. The four components underlying disease spread are the duration of infectiousness, opportunities for transmission (contacts), transmission probability during each opportunity, and population susceptibility.

It is now clear that omicron is more infectious than other variants and so can transmit much more easily. Vaccines are also less effective at preventing infection and severe disease – from over 90% effective against delta (at two doses) to 50%-70% effective against omicron following booster shots. Even more concerning is the impact on the unvaccinated, or those who have only had one or two jabs.

As a result, the current spike is likely to continue well into January 2022. Models predict more than half a million infections, unless more substantial restrictions on social mixing are introduced.

This size of the omicron outbreak could cause several thousand hospital admissions a day, peaking in late January. Such numbers could easily overwhelm the NHS, which is already stretched by the ongoing delta epidemic.

Uncertainties

It is perhaps too early to fully understand the new variant potential for causing hospitalisation and death. Although there is evidence from South Africa, from Denmark and the UK of lower severity, there are enough differences between the countries to make the predictions for the UK difficult. Still, the current estimates of between 400 to 1,200 deaths per day (depending on the scenario) are enough to cause the public health officials to call for stricter control measures to be applied.

Our World in Data

Another big uncertainty in the predictions is the level at which the public will obey restrictions aimed at stopping the virus from spreading. Social mixing over Christmas is likely to increase infections, although substantial restrictions have already been announced in Scotland and Wales and are being considered in England and Northern Ireland. These measures follow restrictions imposed in other countries like Germany or Sweden.

Mask wearing and other simple hygiene measures reduce the possibility for the virus to spread. Even more importantly, winning the race between the variant spread and booster vaccination is essential to reduce susceptibility and protect the already stretched NHS. The UK is well-positioned in this respect, although logistic challenges might slow down the ambitious programme of booster vaccination.

Forget about herd immunity

The omicron spread has significance for COVID epidemiology beyond the immediate impact on public health. Herd immunity has been hailed as a key concept behind COVID control strategies. The underlying assumptions are that the population can gain sufficient levels of immunity through either vaccination or past infection to stop the virus from spreading. Omicron emergence and rapid global spread has clearly shown that, for such an organism, herd immunity is not possible in the long run.

New variants will probably continue to arise and repeated vaccinations and continuation of control measures will be needed to counter these future threats.

![]()

Adam Kleczkowski receives funding from the UK Research and Innovation and the Scottish Government.