In the same week that saw at least 27 people die in the Channel trying to cross in a small boat, the UK government released its quarterly immigration statistics bulletin.

Political pressure has piled up on the UK government – and on Home Secretary Priti Patel in particular – to take action. In turn, she has deflected blame onto the allegedly overgenerous “broken” asylum system for encouraging people to attempt the crossing in the first place.

Since the tragedy, the government narrative has shifted from the bombastic “stop migrants to defend our border” to the more humanitarian-inflected “stop migrants (in France) to protect them from drowning”.

The data show that in the year ending June 2021 (the latest available comparable statistics) the UK received 31,235 asylum applications – fewer than France and Spain and far behind Germany, which received 113,625.

Counter to what one might expect from media reports, the British “summer of migration” (echoing an expression used in Germany in 2015) was pretty much in line with previous trends in terms of asylum applications.

The Channel tragedy has been used by the UK government to drum up further support for changing the rules on claiming asylum in the UK.

It’s important to assess the reality of this situation so that the government cannot exploit legitimate humanitarian concerns about the risks migrants take when crossing the Channel to legitimise further curtailing their right to claim asylum.

More people are not being granted asylum

One of the faults of what Priti Patel calls the “broken asylum system” is its alleged generosity – as interpreted through the high success rate of asylum applications.

At a first glance, the current success rate in the UK (64%) is higher than in countries like Germany (39%) and France (23%). However, this may be the result of differences in how countries managed the COVID disruption. In the case of the UK, a minority of relatively straightforward cases were decided quickly during the pandemic. And because they were straightforward cases, they were likely to result in asylum being granted. The consequence is a success rate over the past year that is significantly higher than in previous years. The flipside to this is that many cases were left undecided and an overwhelming backlog has accumulated.

The reality on the ground is that there is a very large pending caseload. Thousands of people are living in protracted uncertainty. They are surviving on limited state subsidies with no right to work – which is especially striking given the lack of low skilled workers in several areas of the labour market and struggle with recruiting.

People will continue to try to reach the UK

Another important fact coming out of the government’s asylum figures is that the top five countries of origin of asylum applicants in the UK are different from the EU’s main destination countries (Germany, France, Spain, Italy and Greece). Despite what we hear often in media and political commentaries in the UK, not every asylum seeker is heading to the UK. But some will continue to try to do so.

In the EU, most people claiming asylum come from Syria and Afghanistan. In the UK, the main countries of origin are Iran, Eritrea, Albania, Sudan and Iraq. This difference is mostly due to the role played by family, historical and geopolitical connections in shaping decisions about where to move to and settle.

What this means is that the people are attempting to cross because they have strong motivations to come to the UK, while other asylum seekers in Europe do not. More boots on the ground and boats in the sea may be able to stem a flow through a particular route temporarily but they do little to combat the underpinning drivers. A more likely outcome is that new, more expensive and dangerous, routes will emerge to meet demand.

This is ‘worse than 2015’

In presenting the latest figures, the government chooses to highlight that the rate of asylum applications is “higher than at the peak of the European migration crisis in 2015-16”. These choice words are misleading because the migration crisis unfolded largely on mainland Europe rather than the UK. When people hear “worse than 2015”, it contributes to the overall narrative of the UK being “invaded” by unauthorised migrants. The reality is that there has been only a small increase to an already comparatively small figure.

More safe routes

New measures planned as part of the nationality and borders bill making its way through parliament will make it even harder to claim asylum in the UK. These changes are being brought in under the guise of curtailing people smugglers and closing unsafe routes to the UK.

The government has already said it wants to penalise people for attempting to reach the UK by boat, describing these journeys as “unmeritorious”. This clearly signals that applicants entering the UK are not considered deserving of asylum – even before they make a claim.

Future support will be channelled into specific refugee resettlement schemes, which are presented as “safe routes” into the UK. But these offer help to extremely limited numbers of people who meet the government’s specific requirements.

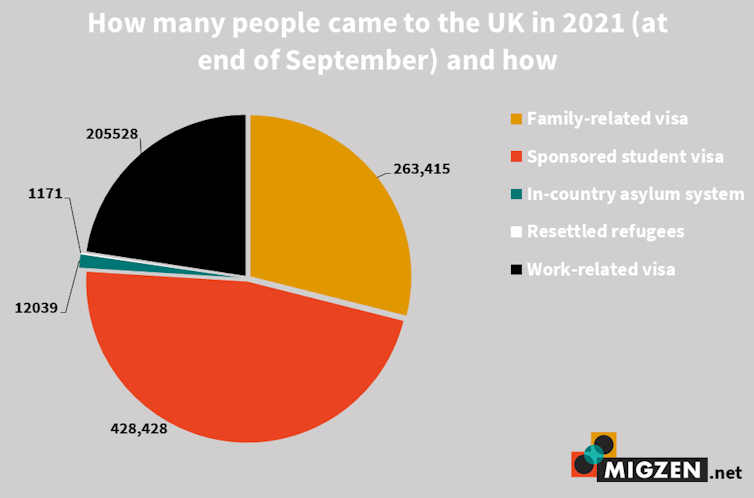

MIGZEN, Author provided

The government is presenting these small scale schemes as a viable alternative to having a fair and working asylum system in the UK. This is far from true and we should be wary of the resettlement of a small number of refugees being used to justify a draconian approach to the right to claim asylum of the many.

![]()

Nando Sigona receives funding from the UKRI/Economic and Social Research Council for 'Rebordering Britain and Britons after Brexit' (ES/V004530/1). For info www.migzen.net

Michaela Benson receives funding from the UKRI/Economic and Social Research Council for 'Rebordering Britain and Britons after Brexit' (ES/V004530/1). For info www.migzen.net