We make decisions every day, many of which are so straightforward that we hardly notice we are making them. But we tend to struggle when faced with decisions that have uncertain outcomes, such as during the pandemic. Cognitive scientists have long been interested in understanding how people make such uncertain decisions. Now our new research, published in the journal JAMA Network Open, gives a clue.

Scientists typically test decision-making under uncertainty using “probabilistic tasks”, in which study participants can choose from two or more options, each with a specific probability of providing a reward (usually points or money). This could be a game, for example, in which you have to choose between a picture of an apple or a banana on a computer screen. The apple might be programmed to give you points 80% of the time while the banana will do so 20% of the time, but during the game the probabilities can change. You would not be aware of the probabilities at any given time, however – leading to uncertainty. Your task would be to find out which option is more rewarding.

Humans generally use two decision-making strategies when faced with uncertainty: exploitation and exploration. Exploitation involves frequently choosing options that are familiar and provide a higher certainty of reward. Exploration involves trying out choices that are unfamiliar. In an uncertain and changing environment, it is thought that the best strategy is to flexibly alternate between exploration and exploitation.

Whether people explore or exploit depends on the situation at hand. When under time pressure, people are more likely to repeat old choices and explore less.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

A common symptom of many psychiatric disorders is difficulty in coping with uncertainty. People suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), in particular, feel incredibly uncertain about their thoughts, feelings and actions, and may feel anxious. They may feel doubtful over whether they counted the number of tiles accurately, or whether they scrubbed their hands thoroughly enough.

In our study, we demonstrate that people with OCD struggle to make decisions when they are uncertain. We asked 50 teenagers with OCD and 53 teenagers without OCD to complete a probabilistic task, in which the probabilities associated with each option would reverse halfway through the task (for example the apple picture would go from giving a reward 80% of the time to 20% of the time). The ideal strategy would be to exploit the more rewarding choice early on (apple), but then engage in exploration (pick banana) once you’ve noticed a shift in how often points are offered.

Teenagers with OCD did not do this, however. Across the task, they displayed a great deal of exploration of choices. They showed a tendency to switch choices and select the less rewarding choice more often than teenagers without OCD. Fascinatingly, when teenagers with OCD performed another task which was not probabilistic and didn’t trigger uncertainty, they showed no problems with decision-making.

Uncertainty caused by the probabilistic task may have caused teenagers with OCD to doubt their decisions and feel the need to “check” the less rewarding choice frequently. This exploration could be a strategy for them to try to seek out information until they feel certain. Intolerance of uncertainty is a plausible reason for why people with OCD feel compelled to check items like locks, stoves and switches in daily life.

The results also suggest that many people may start to explore in this way if they are feeling uncertain enough.

Pandemic uncertainty

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a great deal of uncertainty for everyone, which in turn seems to have increased our tendency for exploration in the form of information-seeking. A study has shown that perceived uncertainty has led to people seeking more information about COVID via social networking apps and online news media.

On the one hand, this has led to more preventative actions, such as increased hand washing and mask wearing, which can reduce uncertainty and keep people safe. On the other hand, this information-seeking may not be entirely beneficial. A recent study has shown that since the onset of the pandemic, otherwise healthy people are reporting more obsessive-compulsive symptoms, such as constantly checking for new information to reduce feelings of pandemic-induced uncertainty.

Semnic

Excessive information-seeking during this period can lead to high levels of stress. We know from previous research that it can eventually lead to burnout and avoidance of information altogether, leaving people less informed about government guidelines, safety measures and COVID-19 treatment advances.

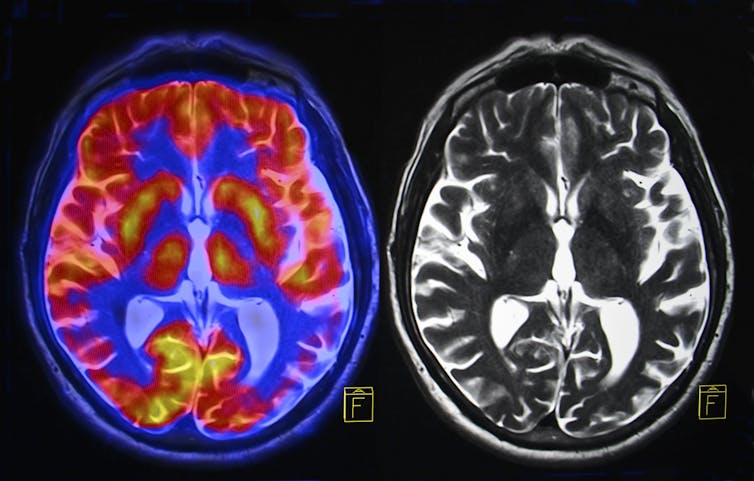

Persistent stress from overexposure to distressing news may also cause changes in key brain areas such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which are responsible for memory and cognition. This can in turn result in reduced rational decision-making, leading us to rely more on emotions. This could make us susceptible to believing misinformation and engaging in irrational behaviours, such as hoarding toilet paper.

Luckily, there are ways to combat pandemic uncertainty by trusting some of the information you’ve already gathered and that seems consistent over time, such as the benefits of masks and vaccines. If you are finding it difficult to cope without frequently checking the news and social media for reassurance, experts recommend setting a timer on social media use, logging out of accounts temporarily, and seeking out more positive, non-pandemic related content online.

There are even evidence-based methods to improving your decision-making under uncertainty, including playing games designed to train your brain, getting good sleep and nutrition, and having social support.

![]()

Barbara Jacquelyn Sahakian consults for Cambridge Cognition. Dr Sahakian’s research is funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Lundbeck Foundation and the Leverhulme Trust and is conducted within the NIHR MedTech and in vitro diagnostic Cooperative (MIC) and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Mental Health and Neurodegeneration Themes.

Aleya Aziz Marzuki received funding as a research assistant and PhD student from a Wellcome Trust Grant awarded to Professor Trevor Robbins (104631/Z/14/Z/) and was the recipient of a grant from the G C Grindley Fund.