Spitzi-Foto/Shutterstock

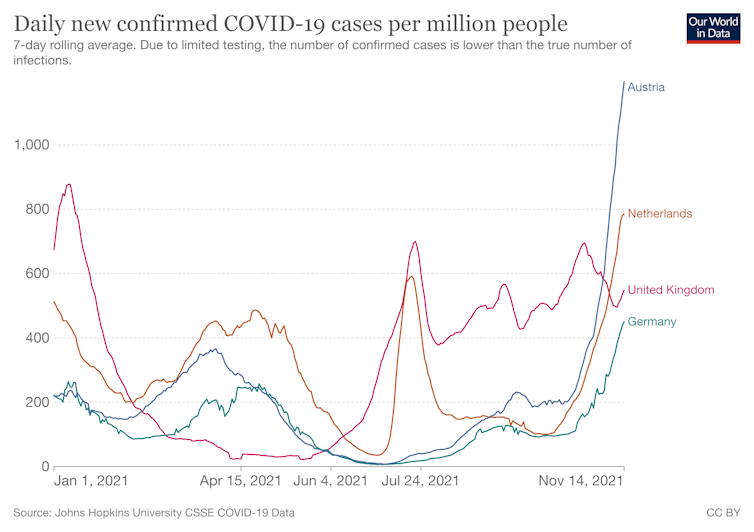

COVID is surging in some European countries. In response, Austria and Russia are planning to reimpose lockdowns, but only for the unvaccinated. Is this ethical?

Some countries already have vaccine passport schemes to travel or enter certain public spaces. The passports treat those who have had vaccines – or have evidence of recent infection – differently from those who have not had a vaccine. But the proposed selective lockdowns would radically increase the scope of restrictions for the unvaccinated.

Lockdowns can be ethically justified where they are necessary and proportionate to achieve an important public health benefit, even though they restrict individual freedoms. Whether selective lockdowns are justified, though, depends on what they are intended to achieve.

One benefit of a lockdown is that it can prevent a country’s healthcare system – especially hospitals – from becoming overwhelmed. If that is the aim, though, there is little need to lock down people at low risk of being hospitalised, such as those who have received a COVID vaccine. But we might also exclude from lockdown young people (even if unvaccinated) who are at low risk of severe COVID (a recent Moscow lockdown took this approach). So this aim would only support a selective lockdown targeted at the unvaccinated elderly or the medically vulnerable, or both.

Alternatively, the primary aim of a lockdown may be to stop the virus from spreading. Since the young and old pose similar risks of onward transmission, this would not support an age-selective lockdown. Yet a lockdown justified on this basis perhaps also should not distinguish between vaccinated and unvaccinated people. That is because vaccines reduce but do not eliminate transmission. The aim of reducing transmission might only support a lockdown of the entire population. And it is not clear that the benefit would be proportionate to the cost of such a lockdown.

Our World In Data, CC BY

A quite different justification for both vaccine passports and selective lockdowns for the unvaccinated is that they might encourage people to have the vaccine. Indeed, John Swinney, deputy first minister of Scotland, claimed that the goal of the Scottish vaccine passport schemes was to increase vaccine uptake.

Clearly, if the goal of new lockdown restrictions is to get people to have the vaccine, it should only apply to those who have not yet been vaccinated.

However, this is ethically dubious. Restricting individual liberty just to make someone act in a particular way often amounts to coercion.

When the stakes are high, it may sometimes be justifiable to impose some degree of coercive pressure to achieve public health goals, for example, to prevent harm to others. But the costs to individual autonomy are considerable, so coercive pressure can only be justified if it is necessary to achieve very valuable goals.

Other methods of increasing vaccine uptake without encroaching on individual liberty, such as education campaigns and the use of incentives, would be ethically preferable.

Inequality

A common objection to vaccine passport schemes, which may also apply to selective lockdowns, is that they treat people unequally. For that reason, some people might be happy with locking down the whole population, but not a particular group – such as the unvaccinated or the unvaccinated elderly.

However, unequal treatment isn’t always unjustified. Even if selective lockdowns treat people differently, this is not necessarily discrimination.. We have previously suggested that in responding to this pandemic, we face a trilemma between liberty, equality and COVID deaths. Selective lockdowns are an illustration of this kind of choice. There are unavoidable ethical trade-offs in our response to a resurgence of the pandemic – we need to decide which ethical values we will prioritise, and which we compromise.

In areas where the virus is spiking, we can reduce COVID deaths and treat people equally by imposing a general lockdown, but that would involve a substantial cost to liberty. One that Austrian chancellor Alexander Schallenberg isn’t willing to take. Defending his country’s selective lockdown, he said: “I don’t see why two-thirds should lose their freedom because one-third is dithering.”

Alternatively, we could treat people equally and not restrict anyone’s liberty. That might put healthcare systems at risk and lead to more deaths.

So selective lockdowns could be justified to prevent a health system from being overwhelmed. They may be unequal, but the alternatives are also unpalatable.

![]()

Jonathan Pugh works for The University of Oxford. This work was supported by the UKRI/ AHRC funded UK Ethics Accelerator project, grant number AH/V013947/1.’ The UK Ethics Accelerator project can be found at https://ukpandemicethics.org/

Dominic Wilkinson receives funding from the Wellcome Trust. This work was supported by the UKRI/ AHRC funded UK Ethics Accelerator project, grant number AH/V013947/1.’ The UK Ethics Accelerator project can be found at https://ukpandemicethics.org/

Julian Savulescu receives funding from the Uehiro Foundation on Ethics and Education, NHMRC, Wellcome Trust, Australian Research Council, UK Research and Innovation (Arts and Humanities Research Council) as part of the Ethics Accelerator Award AH/V013947/1, WHO. He is a Partner Investigator on an Australian Research Council Linkage award (LP190100841, Oct 2020-2023) which involves industry partnership from Illumina. He does not personally receive any funds from Illumina.