Zuma Press Inc/ Alamy

Ever since Margaret Thatcher was in Downing Street, an important part of Conservative party narrative has been the need for low taxes. This goes alongside the fear of excessive deficits that explained why David Cameron and George Osborne opted for spending cuts and austerity when they won the 2010 general election.

Boris Johnson represents a sharp break with this tradition since he wants large-scale spending in order to “level up”. However the same cannot be said about Chancellor Rishi Sunak, who is much more traditional in this respect.

Johnson’s spending plans and the pressures of the pandemic have made raising taxes one of the main themes of this year’s budget, but Sunak has made it clear that he’d rather be cutting them. And at the Conservative conference, he was regularly asked if party supporters could hope to see taxes cut again in the near future.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has reported that if there is no long-term economic damage from the COVID-19 pandemic (a big if) then the tax increases already announced will reduce the state’s borrowing requirement by £30 billion compared with the previous estimates. And at least one report suggests that Sunak and Johnson have agreed to build up a tax-cutting war chest.

That would give the chancellor plenty of room to reduce the tax burden in the run-up to the next general election, thereby giving hope to many nervous Conservative backbenchers who are concerned about retaining their seats. But is cutting taxes as effective a vote-winning strategy as this implies?

Lots of research shows that the economy, particularly growth and employment, is an important factor in influencing electoral support for incumbent governments in democracies across the world, and Britain is no exception. However, there are a number of problems in relying on tax cuts as a mechanism to boost support for the government.

One is that taxation is usually well down the list of salient issues in the minds of the public when it comes to voting. In the most recent tracker poll from YouGov the issue of taxation was in sixth place in importance after health, the economy, Brexit, crime and immigration.

A lesson from history

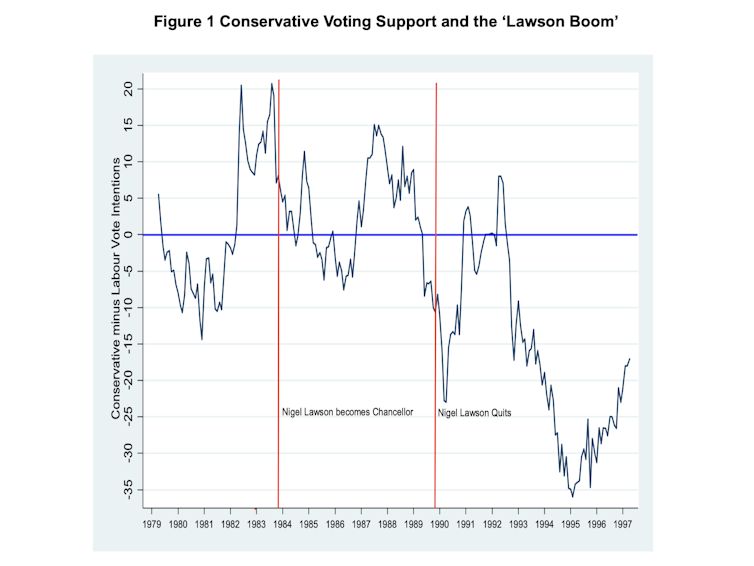

There is also an interesting historical precedent relating to the role of tax reductions in the run-up to an election, which amounts to something of a natural experiment. It occurred after the 1983 general election when prime minister Margaret Thatcher appointed Nigel Lawson as chancellor of the exchequer.

He turned out to be a radical tax cutter, starting with the 1984 budget when he cut corporate taxes, and again in 1985 with cuts in national insurance. When he was in office, the standard rate of income tax was reduced from 30% to 25%, and he reduced the top rate of income tax from 60% to 40%. By any standards, this was a radical change in taxation in a relatively short period of time.

The tax cuts helped to trigger a “Lawson Boom” in the British economy, which reduced the unemployment rate from 12% in May 1984 to 7% by the end of 1989. However, the price paid for this was a rise in inflation from 5% in 1984 to 11% in early 1990.

This was one of the reasons why interest rates doubled to 15% in the space of 18 months, creating a lot of difficulties for banks, companies and mortgage holders. To make matters worse, unemployment then started to rise again.

The interesting question is what did this do to Conservative support in the polls?

Tax cutting produced a boom-and-bust cycle in the economy which, along with the introduction of the poll tax, produced extreme volatility in Conservative support.

Author provided

In 1988 Lawson resigned and the subsequent collapse in support for the government sealed Margaret Thatcher’s fate as prime minister. She resigned after a challenge to her leadership in 1990.

Decision time

Sunak is therefore currently in a dilemma when it comes to the issue of tax cuts. If he produces modest reductions as the election approaches, it’s unlikely to move the dial with respect to public opinion, particularly if he merely reverses the tax increases already in the pipeline.

On the other hand, if he produces large, Lawson-style tax cuts he risks unnerving markets, who are already concerned about inflation and will anticipate another boom-and-bust cycle if this happens.

A third possibility is to try to engineer a quick boom following tax cuts with the aim of reining it in once an election victory is in the bag. The problem with this approach is evident from what happened to Lawson.

It took him nearly three years to reverse a loss of support for the Conservatives in the polls with the tax cutting strategy. It was not until late 1986 that Conservative support turned positive. This is because the effects of tax changes on the economy are slow and indirect, working through other variables such as employment and inflation.

Given that the election must be held by the summer of 2024 and there has been talk of an earlier date, a massive cut and quick boom does not look possible. He would have to reverse the present policy of raising taxes and start cutting them immediately, a very risky strategy to say the least. Overall, it looks like tax cuts are not going to play a big role in influencing the government’s electoral prospects.

![]()

Paul Whiteley receives funding from the British Academy and the ESRC

Harold D Clarke receives funding from ECPR and NSF. No current grants