Orawan Pattarawimonchai/Shutterstock

Beta-amyloid and tau are two proteins that serve useful functions in the brain, but in Alzheimer’s disease – the most common form of dementia – they go rogue and destroy brain cells (neurons). This happens when beta-amyloid forms clumps on the outside of neurons and tau forms tangles and destroys neurons from the inside. This destruction leads to the classic symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: problems with memory and with thinking and reasoning.

Studies have shown that beta-amyloid accumulates in the brain earlier than tau, before any symptoms appear. But our latest study, published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, shows that an early accumulation of tau in the brain is a better predictor of Alzheimer’s related memory decline than an accumulation of amyloid plaque.

Although these proteins are characteristic of Alzheimer’s, their relationship with the disease is not always straightforward. In some cases, the disease might occur even without beta-amyloid in the brain. And beta-amyloid in a person’s brain does not necessarily mean they will develop Alzheimer’s. Still, insight into these proteins gives important information about the signs and progressions of most cases of Alzheimer’s disease. In other words, they are important biological signs, or “biomarkers”, of the disease.

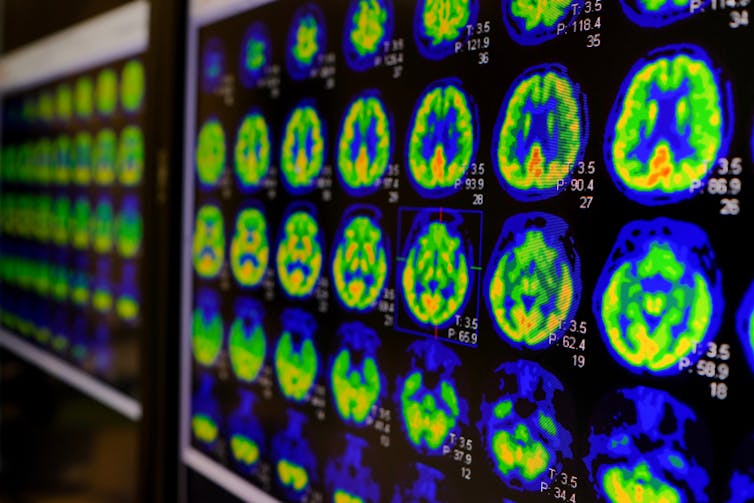

However, until a few years ago, the levels of these proteins in a person with Alzheimer’s could only be measured after the person had died. Today, we can measure these levels in living people using two methods: examining a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (the clear liquid that surrounds the brains and spinal cord) taken with a lumbar puncture, and positron emission tomography (PET) brain scans. The latter uses a special dye called a “tracer” that stains the tau tangles so they show up on the scan.

With the fast progression of research in biomarkers, we are quickly getting better at measuring and detecting early signs of Alzheimer’s in patients. But we still need tests that can predict the development of the disease with greater accuracy.

Utthapon wiratepsupon/Shutterstock

Recent guidelines for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease proposed that biomarkers from PET and spinal fluid were both equally accurate at predicting Alzheimer’s disease. But this view was later questioned by scientists when new evidence showed that biomarkers from PET and spinal fluid do not always agree. There is also a lack of long-term studies showing how the biomarkers are linked to the gradual loss of memory.

Which method is best?

Our study shows that the presence of beta-amyloid in the brain and changes in concentrations of beta-amyloid and tau (a specific form called pTau-181) in the spinal fluid can be detected early in the course of the disease, but they do not seem to have any correlation with later memory loss. In contrast, the presence of tau in the brain measured by PET turned out to be linked to a rapid decline of episodic memory – the memory of everyday events.

Episodic memory is often affected at an early stage of the disease, and our study suggests that looking for tau using PET scans is the best way to predict early stage Alzheimer’s.

Our results are based on brain imaging (PET) and spinal fluid analyses in a group of 282 participants comprising people with mild cognitive impairment, people with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy people (the control group).

Among these, 213 participants were also monitored for three years with tests of short-term memory related to daily events. PET scans showed that 16% of the participants had a buildup of tau. This was associated with them having more rapid memory decline than participants without tau accumulation, regardless of the beta-amyloid accumulation in the brain.

Tau accumulation in the brain (as shown by PET scan) was also more accurate than tau measured in spinal fluid at detecting a short-term memory decline. In other words, the tau spinal fluid test was negative in some cases, while the tau PET scan was positive for the same subject. This confirms that lumbar puncture and imaging methods are not always comparable.

Interestingly, over 30% of the participants with tau accumulation in the brain had no or little cognitive impairment at the start of the study, revealing how tau can accumulate at the early stage of the disease without showing ill effects and still predict the subsequent decline in short-term memory.

Next-generation tracers

Even though the tau PET turned out to be more accurate than other biomarkers in predicting a decline in short-term memory, the first-generation tau PET tracer used in our study has its limitations.

Any PET tracer, ideally, is supposed to bind only to the target molecule (tau) in the target organ (brain), but in the first-generation tracers, it also bound to unwanted structures that showed up in the scan. This is called “off-target binding”. Its presence can be verified by post-mortem studies on slices of brain where you can see where the tau tangles are.

In the future, more specific tau tracers (second generation) will hopefully minimise the off-target binding and provide better options to predict more accurately how the disease will play out.

![]()

Marco Bucci does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.