Varavin88/Shutterstock

Back in the summer of 2021, the UK government’s pandemic modellers predicted that there would be a significant COVID outbreak in the autumn. Yet so far, this hasn’t happened. Other countries with good COVID vaccine coverage have also seen their cases fall and then stabilise. So is herd immunity finally arriving?

Reaching a level of immunity across the population that’s sufficient to stop the virus spreading has been a goal since the beginning of the pandemic. Initially it was hoped natural exposure to the virus would get us there. Yet data from Brazil, India and Iran (some of which is in preprint, and so still needs to be formally reviewed) suggests that herd immunity through natural infection wasn’t achieved in these places despite several waves of infection.

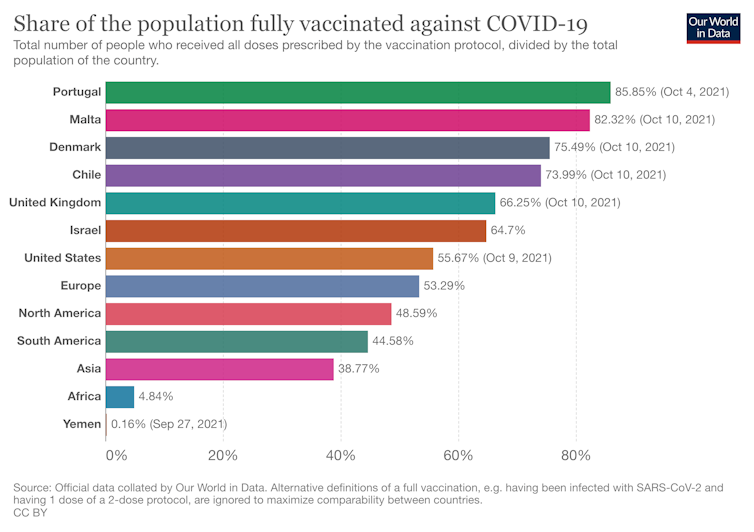

But many countries – such as Portugal, Malta, Denmark and Chile – have now managed to fully vaccinate 70% to 80% of their population, including children. As a result, their overall levels of immunity – when counting vaccine-based and naturally acquired immunity – are very high, allowing for the removal of most, if not all, regulations.

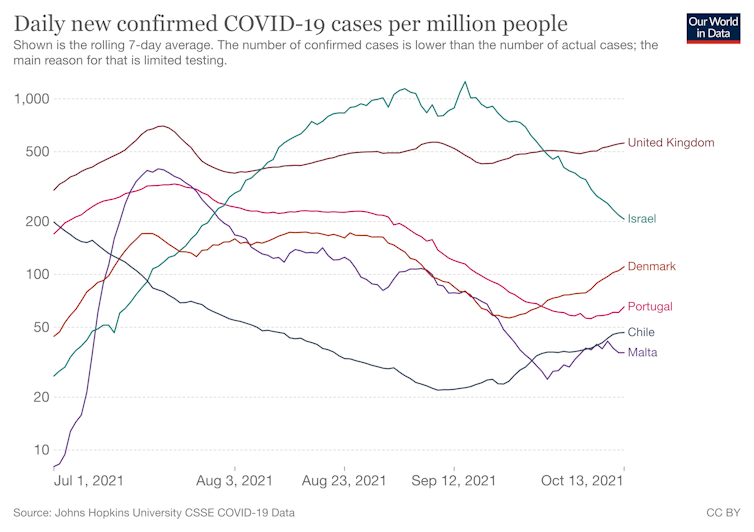

When immunity levels are high like this, models suggest there will be a rapid decline in COVID-19 cases. But while cases have fallen in these countries over the past months, they’ve now plateaued, and in some cases seem to be creeping up again.

This inability to drive cases down further is probably due to a number of factors. Principally, there’s the rise of the delta variant, which is more transmissible. This, above all else, has put to rest the hope of quickly getting rid of COVID. The more infectious something is, the more people need immunity to it and the stronger that immunity needs to be to stop it spreading.

And while the vaccines available provide exceptionally high protection, it’s not total. Some vaccinated people will still get COVID. There’s also growing evidence that immunity – from vaccination or infection – fades over time.

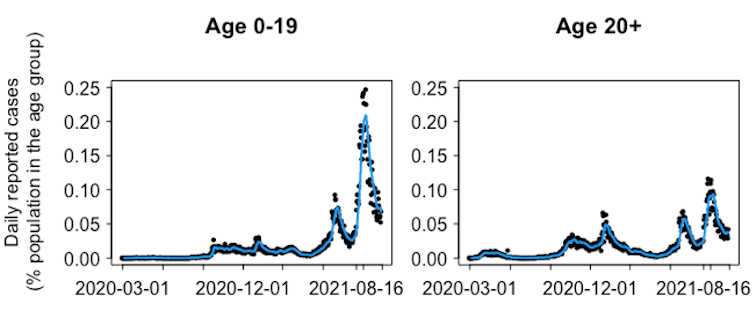

Immunity may also be spread unevenly across the population. Outbreaks that are happening right now in the UK are concentrated in those parts of society where susceptibility is still prevalent, such as in schools. Delaying vaccinating schoolchildren has led to severe outbreaks in young people, with cases in Scotland, for example, exceeding any past peaks in these school-age groups.

Adam Kleczkowski

These factors explain why cases aren’t being completely driven down. In fact, they are the reason why many modellers predicted that with measures to control the virus removed, we could see a massive outbreak. And yet, in many highly vaccinated countries, the numbers are seeming neither to massively explode nor quickly decline. Why?

Well, the current plateauing of cases could be caused by feedback between the perceived risk of COVID and the lifting of protection measures. Despite restrictions having been relaxed, many are still cautious about going out and socialising. Masks, hand washing and social distancing are compulsory in many countries and regions, but even where they’re not many people are continuing with them. Use of public transport is still down compared to pre-pandemic levels and working at home is still prevalent in many places. Some countries have also introduced vaccine passports.

These largely voluntary behaviours may be counterbalancing the virus’s ability to defy immunity levels and spread.

What’s likely to happen next?

What we’re seeing now may be what the pandemic looks like in the weeks and months to come. Outbreaks may well be limited, with an increasing proportion of cases in the vaccinated population, simply because almost everybody is already vaccinated.

Superspreading events, like Euro 2020, might temporarily increase cases. Although repeats of large waves from last winter or last summer are unlikely, bringing down case numbers will be challenging. For some countries, like the UK, high levels of infection will probably persist for the foreseeable future.

Looking further forward, three possible future scenarios have been identified. In the first, the world will face returning waves of severe disease with high infection levels. This is possible if immunity starts waning rapidly or if new mutations arise and the virus persists in unvaccinated pockets worldwide.

Many diseases in the pre-vaccination era – like measles, plague or smallpox – exhibited devastating cycles. Epidemics were characterised by long spells with low infection levels, during which a susceptible population built up as new, non-immune children were born. These periods were followed by catastrophic outbreaks. This process could repeat itself two, three or even more times.

A second scenario could see COVID transition to being an epidemic but seasonal disease, like seasonal influenza, which occasionally erupts into pandemics, such as the 1889-90 Russian, 1918 Spanish or 2009 swine flu outbreaks. Despite being seen as “normal”, influenza still causes suffering, resulting in a high health burden to society and, in some years, high death rates. Other diseases, like cholera, also show seasonal patterns.

In the third scenario, we might see the coronavirus evolving towards being less severe, perhaps becoming like the common cold. Of course, new variants could change the picture, but potentially there are now fewer opportunities for this to happen because delta is so infectious, it is hard for other variants to out-compete it and gain a foothold.

It is too early to say definitively what “living with the virus” will look like, both in the short and long term, given this range of possibilities. However, it seems very unlikely that herd immunity is going to result in the virus ceasing to be a problem.

What’s almost certain is that the pandemic will have a long tail that is massive and uneven, and which is likely to have a disproportionate impact on the vulnerable, those living in deprived areas and pregnant women. It’s also clear that vaccination alone won’t be enough to suppress the virus. Simple restrictions, like masks, vaccine passports or frequent testing, will continue to be part of our lives.

![]()

Adam Kleczkowski receives funding from the UK Research and Innovation and the Scottish Government.