Young people in the UK have reportedly taken up university places at record levels in 2021. Some institutions have over-recruited and now face great pressure on their resources. Students are having trouble finding places to live and seats in lecture halls. Some universities are paying students to defer their place.

Our research draws attention to an earlier moment of expansion in higher education. The aftermath of the first world war saw an unprecedented growth in student numbers. As a result, universities and colleges had to find temporary solutions for teaching space and student accommodation.

At the time, the challenges of this expansion were much noted. The Northener, the student magazine of Armstrong College in Newcastle, put it plainly in March 1919: “We shall be bulging out of our classrooms and sitting on the window-sills.”

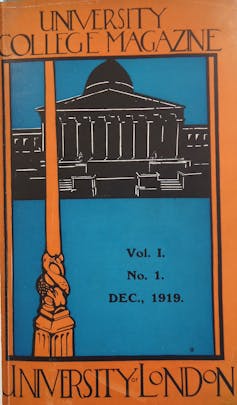

Author provided

A contributor to the November 1919 edition of the University of Liverpool’s student paper, The Sphinx, reported that some of their peers were being turned away “from the pursuit of knowledge, there being no more room to seat them”. And, in a report that same year, council members at Mansfield College in Oxford predicted that the colleges would be “overflowing” by 1920. “The problem of housing”, they wrote, “will be very acute”.

Government initiative

This influx of students was a direct consequence of the Great War, as many young people had been forced to interrupt or postpone their studies. As our research shows, another important factor in driving up numbers was the major funding scheme the government put in place to support the higher education of ex-servicemen.

From the winter of 1918–1919 until 1923, the scheme provided grants for nearly 28,000 students across England and Wales. In Scotland, a similar initiative funded the studies of over 5,800 former soldiers.

Ad Meskens, CC BY

Drawing on archival evidence from the Board of Education as well as university records from Aberystwyth, Durham, Liverpool, London, Newcastle and Oxford, we have shown how these grants helped war veterans access higher education and reintegrate into public life. As the Guild of Students at the University of Liverpool put it in its handbook for the 1918-1919 academic year, “more than in the past, the Universities are to play a larger part in the life of the nation”.

As a result of these post-war measures publicly funded ex-service students constituted around half the student body at many universities between 1919 and 1923. And, as highlighted by the student publication of the University College of Wales, The Dragon, they had a distinct outlook. “The Ex-Service men came like a fresh wind from the world without”, the magazine reported in February 1921, “bringing with them a greater knowledge of men and things, a wider range of practical experience, a more critical spirit and a greater impatience of traditional shackles”.

Closer cooperation

Commemoration of the fallen was an important feature of university life in this period. Institutions compiled rolls of honour, created photographic displays and raised money for permanent memorials to those who had not returned. At the same time, the ex-service generation demonstrated a strong desire to rebuild student life. New societies were formed, varsity sports fixtures resumed, and dances and student rag festivities flourished.

Author provided

There was a growth in student clubs with a focus on politics and international affairs. Some societies supported the newly founded League of Nations. Others channelled funds and gifts-in-kind to students abroad, for example through European Student Relief, a humanitarian organisation in Geneva.

Writing in the March 1922 edition of The Sphinx, students at Durham University said that “the student world of to-day has a thorough grasp of the need for the closer co-operation of nations and the establishment of international relationships on mutual understanding and goodwill”.

Today, under very different circumstances, campus life is restarting after a time of disruption. Student societies and unions continue to have a major role in the reconstruction of university life – as does the National Union of Students, which celebrates its centenary next year. When the latter was founded in 1922, it was an important expression of the hopes for a more peaceful future.

![]()

Georgina Brewis receives or has received funding from the ESRC, the AHRC, the Swedish Research Council, the British Academy and the Society for Educational Studies.

Daniel Laqua receives or has received funding from the AHRC and the Society for Educational Studies.

Rowan Thompson receives or has received funding from the Institute of Historical Research and the Society for Educational Studies.